A Great Miracle Occurred Here

Clifford R. Goldstein January/February 2015Having been raised in an exceedingly secular Jewish home, I have few memories of Jewish holidays, for the simple reason that we didn’t observe them. However, somewhere deep in the recesses of my mind are stored images, probably from the early 1960s, of Chanukah celebrations. Specifically, I remember playing with a dreidel, a four-sided spinning top with a Hebrew letter on each side, which together stand for, Nes gadol haya sham: “A great miracle occurred there.” I remember also being told that many centuries ago pagan soldiers would not let the Jews study the Torah. In order to get around this prohibition, the Jews would bring dreidels with them when they secretly delved into the holy writings. Thus, if soldiers came, they would hide their scrolls and pull out the tops, deceiving their oppressors into thinking that they were merely playing a game, as opposed to doing something as subversive as reading Scripture.

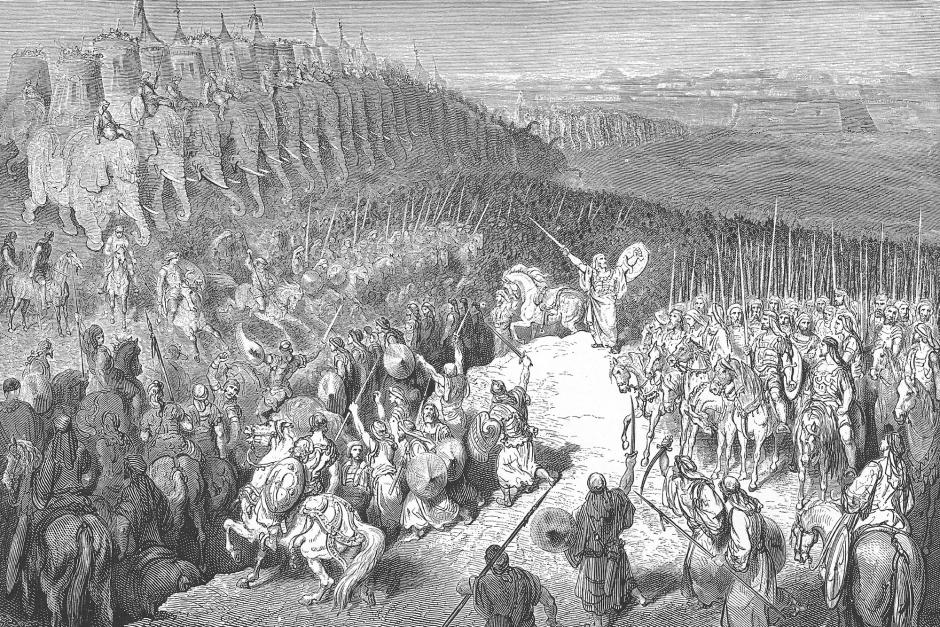

However steeped in tradition Chanukah dreidels might be, those traditions did arise from one of the greatest crises in Jewish antiquity. Known as the Maccabean revolt, it’s a story of a popular rebellion against an oppressive ruler who threatened to eradicate the Jewish faith in Judea. Some scholars even argue that the Maccabean revolt was the first recorded war in history ever fought over religious freedom.

What was the story of the Maccabees, and what might it teach us about the continued struggle for religious liberty?

Geographic and Cultural Factors

Putting aside its apocalyptic prophecy, the Old Testament narrative begins with the creation of the world and ends with the return of the Jews to their native homeland after the Babylonian captivity, circa sixth century B.C. This return from exile occurred under the Persians, who—by the fifth century B.C.—were facing the onslaught of the Greeks, whose hegemony climaxed under Alexander the Great (356-323 B.C.). In 332 B.C. the Greeks conquered Judea, and while being conquered was nothing new to the Jews (having faced this before by Assyria, Babylon, and Media-Persia), this conquest presented a unique challenge.

“In previous conquests,” writes Lee Levine, an historian at Hebrew University, “Israel had invariably remained at the periphery of world empires, far from the seats of power and authority. Its marginal geographic location assured the Jews a measure of stability and insulation.” However, with the breakup of the Greek Empire after the death of Alexander, the small Hebrew nation found itself sandwiched between the battling forces of the Seleucids (based in Syria) and the Ptolemies (based in Egypt). For the next century the two kingdoms warred with each other on Judean soil. Finally, in 198 B.C. the Seleucids beat their rival there, and Judea was incorporated into the Seleucid kingdom.

This victory presented the small nation with a challenge that it had not faced under its previous conquers, the Persians. Under Persian control the Jews were actually encouraged to rebuild their religious and indigenous institutions and traditions. All the Persians wanted was political loyalty, and taxes. Whatever humiliations and problems the occupation presented, religious freedom generally remained secure.

Under the Greeks things were different. Never suffering from a lack of hubris, the Greeks weren’t satisfied with a mere military conquest. Believing in a kind of “manifest destiny” to spread their culture, institutions, ideas, and way of life to “barbarians” (anyone not Greek), they worked very hard, and quite successfully, to do just that. Now, having conquered more “barbarians,” this time in Judea, the Greeks were determined to continue their process of Hellenization, even in the land that God promised the descendants of Abraham many centuries earlier (Genesis 12:7).

Hellenized Jews

It was working, too. Though scholars debate how far Hellenization went, it took a certain hold. Within a century after the conquest of Alexander, Greek cities (each known as a polis), which became centers for promulgating Greek ideas and culture, were founded in various parts of Judea.

The problem was exacerbated by corruption in the priesthood, which served as the de facto political leadership in Jerusalem at that time. Two corrupt priests, Jason and then Menelaus, both passionate Hellenizers, helped make Jerusalem look more and more like a Greek polis than the capital of God’s covenant people and the chosen site of the sacred Temple. During their rule the first gymnasium—a Greek center for both intellectual and physical education—was built in Jerusalem. According to 2 Maccabees 4 (the book of Maccabees being a key source for this period), Jason did away with Jewish law and introduced Greek customs into the city: “With great enthusiasm he built a stadium near the Temple hill and led our finest young men to adopt the Greek custom of participating in athletic events.”

Internecine fighting between the followers of Jason (who weren’t seen as Hellenistic enough) and those of Menelaus led to the violent intervention of the Seleucid overlord, Antiochus IV Epiphanes, in 169-168 B.C.

From Sinai to Olympus

Though previous Seleucid rule had been relatively benign, everything changed under Antiochus IV Epiphanes. Though no consensus exists why he initiated his terrible oppression of the Jews, his actions were unprecedented in the ancient world. Pagan conquerors would, at most, impose their gods upon the locals, but never would they prohibit them the practice of their own religious traditions.

With Antiochus IV, all that changed. First he pillaged the Temple, and then with unbridled fury Antiochus IV sided with Menelaus against Jason and ravaged the latter’s followers. Not far from the Temple Mount he built a fortress for his troops right in the city. More foreign troops inevitably meant more foreign religious cults in the Holy City.

Then, however, came the outright prohibition of the practice of the Jewish faith: the faith that the Hebrews had been following, in one form or another, since (one could argue) Abraham, or certainly at least since the covenant at Mount Sinai. In 167 B.C. Antiochus IV issued a decree that banned circumcision, the study of the Bible, and observance of holy days, which included the Sabbath and the festivals. He forced the Jews to eat unclean food and to commit idolatry, often seen as the most unpardonable of sins.

According to Josephus: “Now Antiochus was not satisfied either with his unexpected taking the city, or with its pillage, or with the great slaughter he had made there; but being overcome with his violent passions, and remembering what he had suffered during the siege, he compelled the Jews to dissolve the laws of their country, and to keep their infants uncircumcised, and to sacrifice swine’s flesh upon the altar; against which they all opposed themselves, and the most approved among them were put to death.”

And perhaps worst of all, Antiochus IV Epiphanes decreed that the Jews worship the Greek god Zeus, rather than the God of Israel. The people whose religious identity was heavily forged at Sinai were now forced to bow before the chief “deity” of Olympus. Truly, this was a full-fledged assault on religious liberty.

The Maccabean Revolt

It’s no surprise that, in the face of such an attack on their religion, and hence their national identity, the Jews did revolt. Armed conflict started in a remote town, called Modi’in, where a priest named Mattathias and his five sons, including one called Judas Maccabee (who led the revolt after Mattathias died), became the leaders. Mattathias sparked the resistance movement by striking a Jew who was preparing to offer sacrifice to foreign gods, and then by killing the king’s officer, who was standing by and watching. 1 Maccabees 2 described the scene like this: “Just as he finished speaking, one of the men from Modi’in decided to obey the king’s decree and stepped out in front of everyone to offer a pagan sacrifice on the altar that stood there. When Mattathias saw him, he became angry enough to do what had to be done. Shaking with rage, he ran forward and killed the man right there on the altar. He also killed the royal official who was forcing the people to sacrifice, and then he tore down the altar.”

Thus began the Maccabean revolt, a guerrilla campaign against the forces of Antiochus IV that, despite the odds against the rebels, was so successful Judah earned the nickname “the Hammer,” or in Hebrew, “Maccabee.” Judah and his soldiers—including some pious Jews, the Hasidim (who refused to fight on the Sabbath, thus at times incurring terrible losses)—continually attacked Seleucid armies that attempted to reach Jerusalem and reinforce the garrison there. Despite one setback, south of Jerusalem, the Maccabees made steady progress until, in 164 B.C., three years to the month after the persecution by Antiochus began, the Maccabees uprooted the Seleucids in Jerusalem. And though battle with the Greeks continued for years afterward, the main reason for the revolt itself—the banning of the practice of Judaism—was undone. Having overthrown their religious oppressors, the Jews could continue with the faith that they had been following (more or less) since Sinai.

Chanukah and Religious Freedom

And it’s in this success that the celebration of Chanukah, which means “dedication,” arose. Though details remain steeped in tradition, the story goes that after recapturing Jerusalem, the Jews rededicated the defiled Temple to the Lord. However, inside the Temple they found only enough oil to keep the nine-branched menorah (candelabrum) burning for a day. Miraculously, though, it burned for eight days, long enough time to prepare a fresh supply of oil for the menorah.

Since then, an eight-day festival has commemorated this miracle; it falls toward the end of the year, usually in December. It’s even mentioned in the New Testament: “Then came the feast of the Dedication [Chanukah] in Jerusalem. It was winter, and Jesus was walking in the temple area in Solomon’s Portico” (John 10:22, 23, NET)*.

Also known as the “Festival of Lights,” Chanukah has been seen as a celebration of light over darkness, truth over error, and freedom over oppression. Which means that even today it can serve as a reminder of the sanctity of religious liberty, which, unfortunately, still faces the same kind of threats the Jews endured under Antiochus IV Epiphanes.

Whether in the time of the Seleucids or hundreds of years after the Enlightenment, religious faith for millions remains a sacred and fundamental aspect of their own identity, even humanity. Humans are spiritual beings; we sense something of transcendence, something greater than ourselves, of which we believe we are part of, and which helps us understand ourselves and aspire to fulfilling what the purpose of our lives could or should be. This sense is often reflected in religious beliefs, traditions, and doctrines. Thus, to trample upon these expressions of faith is to trample upon people at the most basic level of their humanity.

The Greeks didn’t want to turn the Jews into atheists; they wanted to turn them into Greeks, to follow the Greek way of life and Greek religion. So often the battle for religious liberty is similar: one group seeking to preserve their own religious identity in the face of the pressure of law, or even violence, to change their religion. If people freely chose to do it, as many of the Jewish Hellenists did in the age of the Seleucids—that’s one thing. But to force it upon them, as did Antiochus IV Epiphanes, is another.

Thus, religious liberty remains a fundamental right for all people, and Chanukah (dreidels and all) a symbol of that right.

Article Author: Clifford R. Goldstein

Clifford Goldstein writes from Ooltewah, Tennessee. A previous editor of Liberty, he now edits Bible study lessons for the Seventh-day Adventist Church.