A Turning Point

David J. B. Trim November/December 2010

The middle of the seventeenth century was a key turning point in the history of religious war. The Thirty Years’ War was ended by the Peace of Westphalia (1648), which institutionalized the principle that princes could choose the religion of their state and that their choice was to be respected by other princes, even those who had the same confessional allegiance as a dissident minority of a neighboring prince’s subjects. Fundamentally, states agreed not to wage war on the grounds of religion, but this was counterbalanced by formal recognition that some minorities (though not all) had a right to limited liberty of conscience and worship. Around the same time, the threat posed by the Ottoman Empire (militantly Muslim) to Western Christendom was in decline.

Nevertheless, although religion was no longer the primary cause of conflict, it was still a factor in war in the century after about 1650, as this final article shows.1 In many Christian states policy-making was still shaped by the desire to present a common Christian front against the Turks. And the religious resentments and hatred engendered by antagonism between Catholic and Protestant provided a powerful aid to mobilizing populations for wars, because confessional elements would be emphasized in propaganda by increasingly powerful nation-states.

Having briefly surveyed how the era of wars of religion came to an end, this article concludes by considering Europe’s history of religious wars as a whole. Ultimately, the history that has been surveyed in this five-part series has significant lessons that are relevant to debates over religious freedom in the twenty-first century.

Crusades Against the Turks

As we saw in the last article, the desire of the sixteenth-century French nobility to go on crusade (as their medieval ancestors had done) had been frustrated by their kings’ policy of alliance with the Ottoman Empire. However, the seventeenth century witnessed a new era of French crusading against Islam. In 1664 Louis XIV sent a French expedition to Djidjelli in North Africa. In May 1669 he contributed 60 vessels and around 6,000 troops to a multinational expeditionary force, dispatched under the Papal banner, to help save Venetian-governed Crete; this followed up an unofficial French expedition to Crete in 1668, which had been raised and paid for by French nobles, though with the king’s tacit consent. Thus, insular Christian possessions in the eastern Mediterranean retained the old ability to evoke enthusiasm for crusade. The Turks were victorious, despite the international efforts to save Crete.

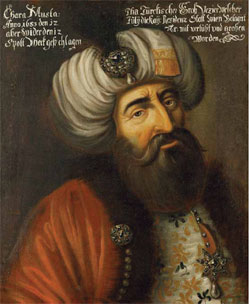

The Ottoman Empire was, indeed, not yet a spent force. It still fielded huge armies against Christian powers in Europe—but to increasingly less effect. In 1664 the Austrians defeated the main Ottoman field army in Hungary, which had seemed on a roll after the Turks’ dismembering of Transylvania. After initial Ottoman triumphs in the Polish-Ottoman War of 1672-1676, Jan Sobieski (King Jan III of Poland-Lithuania) led the Poles to a number of successes and the war ultimately ended in only a marginal Turkish victory.

The celebrated second siege of Vienna in 1683 was a last gasp for the Ottomans in Europe; their attempt to capture the capital of the Hapsburg Holy Roman emperor ended disastrously. The besieging army was virtually obliterated by a relief force led by Jan Sobieski by drawing troops from many European states; the battle that concluded the siege was greeted across Europe, by Protestants and Catholics alike, as a victory of Christianity over Islam. The defeat was so complete that it triggered the gradual reconquest of much of Hungary by a new Holy League. As we saw in the last article, ironically for minority Christian sects, this actually led to a reduction of religious freedom; but the majority Catholic population welcomed the Hapsburg armies as liberators.

All in all, while the Turks were still a significant military power, from the 1660s on they were no longer a threat to the whole of Christendom. There was no longer any prospect of Muslim armies descending into Germany and Italy; while religion was still an important factor in motivating combatants, by this stage the causes of the wars involving the Ottomans were as much geopolitical as religious.

Catholic-Protestant Conflict

Meanwhile in Western and Central Europe, the Thirty Years’ War had finally been ended by the peace treaties of Westphalia in 1648. The Peace of Westphalia is often said to have “put an end to the European wars of religion.” In fact, it did not end confessional conflicts, which endured. However, their intensity was ameliorated by the Westphalian settlement; moreover, from the 1660s onward, they were rarely the cause of war, as opposed to an influence on policy-making and a factor used to generate support for wars waged primarily for secular reasons.

Confessional differences were still the chief cause of rebellions and civil wars. When Louis XIV ended toleration of France’s Reformed Church in 1685, the bloody persecution that commenced led to a sustained, if limited, Huguenot rebellion in southern France, which lasted until 1715. The Catholic Dukes of Savoy used troops to carry out bloody massacres of their Vaudois subjects in 1655 and again in the late 1680s, the latter prompting armed Vaudois resistance until limited toleration was restored. The Williamite War in Ireland (1689-1691) was essentially a struggle between Catholic and Protestant. Similarly, armed support for the Jacobite rebellions in Scotland and northern England in 1689, 1715, and 1745 came almost entirely from Roman Catholics.

Nevertheless, while foreign powers frequently encouraged the internal confessional opponents of their enemies, giving rise to a number of rebellions, there were no examples of major military interventions on the behalf of such rebels, of the sort regularly carried out by governments in aid of foreign coreligionists during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. It is true that, in the 1710s, Catholic persecution of Protestants in the Palatinate (in what today is western Germany) led to so much international tension that, in one historian’s breathless phrase, “a German religious war appeared imminent.”2 However, the fact is that, in sharp contrast to the directly analogous situation almost a century earlier, which was one of the chief causes of the Thirty Years’ War, such a war did not occur. Although policy-makers in Britain and Prussia, in particular, were still influenced by concern for “the Protestant interest,” eighteenth-century efforts to ease the plight of oppressed Protestant minorities were diplomatic, rather than military.3

Secularization of International Relations

Scholars increasingly recognize that religious animosity was still a factor in conflict at the international level.4 As the historian Jeremy Black observes, however, rather than “causing wars in this period,” confessional divisions were “more likely to be resorted to in order to encourage support for and to explain a conflict that had already begun.”5 This was recognized by people at the time. In 1665, “during the second Anglo-Dutch War” (a war fought between two Protestant states that in the previous century had been consistent allies against Catholic Spain), an English pamphleteer “insisted that ‘wars for religion’ were ‘but a speculation, an imaginary thing,” . . . ‘which wise or rather cunning men make use of to abuse fools.’”6

This is symptomatic of the shift in attitudes. It was, to be sure, overly cynical at the time it was written, because even sophisticated people in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were still interested in the plight of coreligionists and could be moved thereby to greater support for a national war effort that aided fellow believers. Many citizens (and indeed statesmen) of Brandenburg-Prussia, Denmark, the Dutch Republic, and Great Britain saw Louis XIV’s France as the embodiment of Catholic aggression. Dutch, British, Danish, and Prussian and other German statesmen played on these feelings to obtain recruits and extra taxation domestically, and international support, for the Nine Years’ War (1689-1697) and the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714). However, British soldiers fought in the latter conflict to defend the territory of the Holy Roman emperor; and Britain’s allies at one time included the Papacy! Nothing could be more indicative of the change in European international relations.

In the middle of the eighteenth century the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748) and the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763) were “widely portrayed in propaganda as a religious conflict,” both in Prussia and in its ally, Great Britain, “a development that was in keeping with the stress on religious animosity” in the internal politics of many European states, including Britain.7 However, these wars did not have confessional causes. Indeed, when the Calvinist King Frederick II of Prussia (“Frederick the Great”) depicted his wars of aggression against Austria as being fought for the Protestant interest, it had terrible consequences for Austrian Protestants. The Hapsburgs took no chances of disloyalty and expelled a number of small Protestant communities, which had been allowed limited religious liberty dating back to the darkest days of the wars with the Ottomans. The threat to the Hapsburgs now came from Protestant Prussia, not the Muslim Ottomans, and Austrian Protestants paid the price. Frederick the Great cared little.

By the middle years of the eighteenth century, then, both international relations and international conflict had largely been secularized. The late eighteenth century was to be the era of international revolution and for the 200 years thereafter, the Western powers were to fight for nationalistic and secular-ideological reasons. They created empires that spanned the globe and spread the notion that this was why wars ought to be waged; they forgot that, for some 300 years, religious war had been an integral part of the experience of Christendom. Only chauvinism made Westerners blind to the fact that, globally, many people still regarded the political process as not being inherently secular. The events of September 11, 2001, were not only a reminder of realities in most of the world, but also a reminder of a largely forgotten era of Western history.

* * *

What, then, can be said about the consequences of the era of wars of religion for religious freedom? Are there lessons for the twenty-first-century world from the experiences of Europeans in the late fourteenth through mid-eighteenth centuries?

Violence and Intolerance Are Not Christian

At times, victory in religious war paved the way for persecution and repression that effectively destroyed a religious minority. Yet on other occasions, wars of religion were still stalemated after decades of bloody combat; the result was to help persuade belligerents that compulsion and violence are futile as means for effecting religious conformity and unity, and frequently are incompatible with the religions in whose name they are undertaken.

The failure of decades of sustained military effort to produce religious conformity and uniformity, or unity out of diversity, was apparent to people of the time. Gradually Christians, in particular, recognized that bloodshed on a sometimes-massive scale, carried out to permit persecution in the name of Christ, was difficult if not impossible to reconcile with Christ’s own teachings and practices. The Roman Catholic chancellor of mid-sixteenth-century France, Michel de L’Hospital, became convinced during the French Wars of Religion that “to think that this division of minds can be settled by the power of the sword and with gleaming armour” was the height of foolishness.8 At the colloquy of Poissy (1561), a rare example of sixteenth-century interchurch dialogue, he encouraged the Catholic delegates not to be too quick to condemn those “of the new religion, who are baptized Christians like they are.”9 L’Hospital wanted all Christians to follow the example of Christ, who, as he movingly wrote, “loved peace, and ordered us to abstain from armed violence . . . ; He did not want to compel and terrorise anybody through threats, nor to strike with a sword.”10

So much of war and violence carries a religious subtext.

So much of war and violence carries a religious subtext.

Violence Is Counterproductive

Here, surely, is a point that Christians would do well to remember. While war in defense of religious freedom may be justifiable at certain times and places, even this can lead to atrocity and the very opposite of the witness Christ wants of the church. And certainly aggressive wars and campaigns of persecution ought never to be an option for followers of Jesus.

By the late seventeenth century the willingness of Christians to shed apparently limitless blood served to delegitimize Christianity. While the coolness to organized religion associated with the so-called “Enlightenment” was to a great extent the product of the discoveries of the Scientific Revolution, it was also a product of the excesses of the Thirty Years’ War—if that was what Christianity was about, reasoned many European thinkers, then Christianity was something they wanted no part of.

At the same time, the millennial, apocalyptic fervor that was so important a factor in generating and perpetuating the wars between Protestant and Catholic could not be maintained forever—especially when the foreshadowed apocalypse simply did not come. In the words of one historian of the English Civil Wars: “As the years passed and the new dawn did not break in the form expected, interpretations of Daniel and the Revelation of St. John became so diffuse that they began to lose their power to rouse and to unite.”11 One result was greater willingness to accept religious plurality within a society—or at least greater reluctance to try to eliminate it with the sword! But another was a massive decline in interest in the apocalyptic books of Scripture, which increasingly seemed irrelevant.

The trend away from persecution, and from warfare designed to facilitate persecution, was neither rapid nor inevitable, but it did lead away from religious war. However, whereas in Britain, the Dutch Republic, and parts of Germany it led to a growing embrace of religious tolerance, it also led to a growing skepticism of Christianity, at least as traditionally understood. This skepticism also helped, in turn, to promote a greater degree of toleration, yet was surely the exact opposite of what the devout and holy warriors who waged confessional wars would have wanted.

Persecution, violence, and torture must always be rejected. Even if it seems likely that they will be limited in terms of geographical extent, who will be affected, and duration, and even if it seems that their effects might be wholly laudable (in religious terms), they must still be rejected by any who believe the teachings of the world’s great religions. Repression can take those who embrace it far from the values of common humanity or Christianity. Religious war is dangerous in its consequences. It would be wrong to say that it ought never to be waged, because at times it can be defensive, protecting people who would otherwise suffer imprisonment, torment, and death. But people of faith ought to be wary—more so than we have historically been—of engaging in wars of religion. Wars have consequences, always; and they can be the opposite of what was expected or intended.

- This article draws on D.J.B. Trim, “Conflict, Religion, and Ideology,” chapter 13 in F. Tallett and Trim, eds., European Warfare, 1350–1750 (New York & Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

- Jeremy Black, ed., “Introduction,” The Origins of War in Early Modern Europe (Edinburgh: John Donald, 1987), p. 5.

- See, for example, Andrew C. Thompson, Britain, Hanover and the Protestant Interest (Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press, 2006).

- For example, David Onnekink, ed., War and Religion After Westphalia, 1648–1713 (Burlington, Vt.: Ashgate, 2009).

- Black, p. 6.

- Steven C. A. Pincus, Protestantism and Patriotism: Ideologies and the Making of English Foreign Policy, 1650-1668 (New York & Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), p. 449.

- Black, p. 6.

- Quoted in Loris Petris, “Faith and Religious Policy in Michel de L’Hospital’s Civic Evangelism,” in Keith Cameron, Mark Greengrass, and Penny Roberts, eds., The Adventure of Religious Pluralism in Early Modern France (New York, Oxford, and Bern: Peter Lang, 2000), p. 136.

- Quoted in Mario Turchetti, “Middle Parties in France During the Wars of Religion,” in Benedict, et al., eds., Reformation, Revolt and Civil War in France and the Netherlands, 1555-1585 (Amsterdam: Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen, 1999), p. 170.

- Quoted in Petris, p. 137.

- I. M. Green, “‘England’s Wars of Religion’? Religious Conflict and the English Civil Wars,” in J. van den Berg and P. G. Hoftijzer, eds., Church, Change and Revolution: Transactions of the Fourth Anglo-Dutch Church History Colloquium (Leiden: E. J. Brill/Leiden University Press, 1991), p. 116.