Ann Lee, A Woman of Great Faith

Boris Boyko January/February 2014The meeting of Shakers started with silent meditation. Ann Lee, a young woman of medium height and serious manner, told them about her vision. She claimed that just as the male and female are seen throughout the animal and vegetable kingdoms, so had God appeared in both forms. “It is not I that speak,” she said. “It is Christ who dwells in me.”

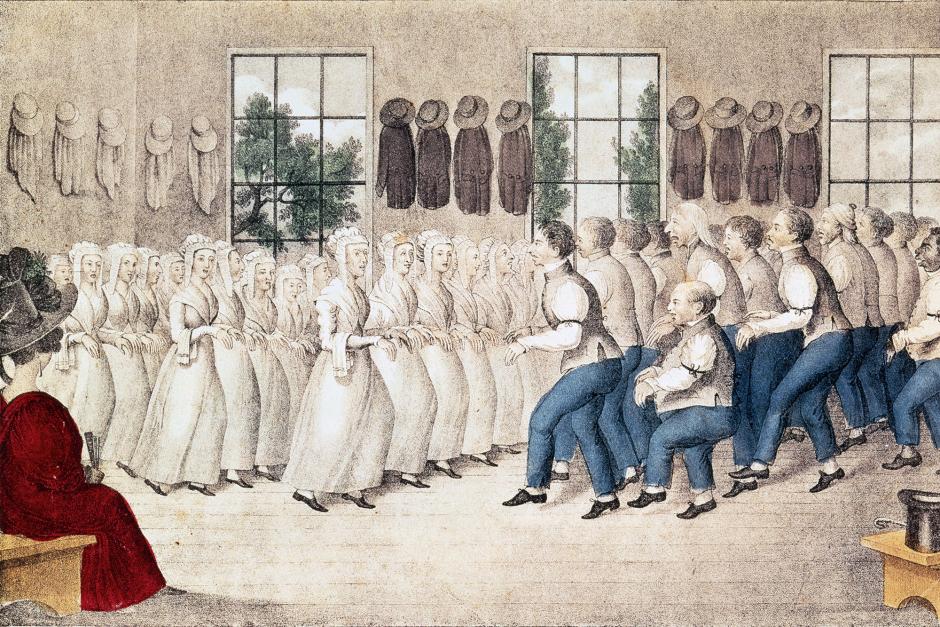

Soon the whole group was taken with a mighty shaking, singing, dancing, and shouting. The Shakers believed that the second coming of Christ was near. They thought that He would appear in the form of a woman. When they heard of Ann’s vision, she was no longer considered by them to be human, but divine. Ann was the one for whom they were waiting!

In 1770 she became their leader, their spiritual mother. They called her Mother Ann or Ann the Word. Ann herself never claimed that honor, nor did she think herself worthy of it. Throughout her life she was persecuted, but her faith carried her on to establish the first Shaker colony in the United States.

Ann was born in Manchester, England, on February 29, 1736, the second of eight children. Her father, John Lee, was a blacksmith from a very poor neighborhood called Toad Lane; no record exists of her mother’s name.

Manchester became known as a textile center during the Industrial Revolution. New machines sped up the clothmaking. People from the countryside poured into Toad Lane, doubling the population to 20,000 between 1719 and 1739. Whole families worked for low pay from dawn till dark. They were crowded into filthy little rooms. There was much disease, and the infant death rate was high.

Ann had no schooling. During her childhood she lived amid the mud, noise, and odors of Toad Lane. Before she reached her teens, she worked in a textile factory, first as a cutter of velvet and then as a helper in preparing cotton for the looms. Later she became a cutter of hatters’ fur. She was also a cook in an infirmary in Manchester. A serious-minded girl, Ann was always faithful and neat about her work.

When she observed the sin and despair in Toad Lane, Ann felt there must be a higher purpose to life. She looked for hope in religion. Cathedral square was nearby, but she thought the official church too sedate. She longed for something stronger.

At the age of 22 Ann met a tailor and his wife, James and Jane Wardley. The Wardleys had been Quakers, but couldn’t find the inner peace they wanted. They also searched for a religious answer to the suffering around them.

While in London the Wardleys had joined a group called the French Prophets, also known as the Shaking Quakers, or Shakers. The French Prophets came from the mountains of southern France, where they were called Camisards. They were exiled from their homes because of their radical ideas and manner of worship.

Why did they shake and dance during worship? the Shakers were asked. The answer was that their form of worship was based on the customs of the Old Testament. When the Israelites escaped from the Egyptians at the Sea of Reeds, Miriam “took a timbrel in her hand; and all the women went out after her with timbrels and with dances” (Exodus 15:20). In another passage David was seen “leaping and dancing before the Lord” (2 Samuel 6:16). The words of the psalmist said: “Let them praise his name in the dance” (Psalm 149:3).

In London the Shakers were ridiculed. They attracted only a few followers. Most of them left to go to other countries, but the Wardleys decided to start a group in Manchester. In 1758 Ann joined the Wardleys, which consisted of about a dozen members.

At first the young woman with fair complexion, blue eyes, and chestnut-brown hair did not stand out in the meetings. She was so mild-mannered and pleasant that many wondered why she had not married. Later she attracted attention when she shouted out against sin.

Ann believed that all fleshly relations between men and women were a sin. She never condemned marriage, but thought it less perfect than celibacy. She thought that after children were produced, the life of sex must be replaced by the life of the soul.

But on January 5, 1762, Ann did marry (at her father’s insistence). At that time she was still a member of the Church of England, for the banns were signed, by mark, by Ann and Abraham Standerin, or Stanley. (The cathedral records were unclear about the last name.)

Abraham was described as a kindly man who was employed as a blacksmith in Ann’s father’s shop. The couple made their home with her parents. In the next four years four babies were born, but each lived only a few months. In 1766, after the death of her last child, Ann became very ill. She thought that her marriage was sinful and that God was punishing her. After a time of great remorse, she had the vision that caused her to become Mother Ann.

When Mother Ann began to direct the Shakers’ activities, the persecution began. In the summer of 1773 she and four others were arrested and each fined £20. Because they were unable to pay, they were thrown into jail.

Once, when she suffered from a stoning, Ann said, “I felt myself surrounded by the presence of God, and my soul was filled with joy. I knew they could not kill me, for my work was not done; therefore I felt joyful and comfortable, while my enemies felt confusion and distress.”

Another time a mob dragged Ann out of a meeting. She was confined for two weeks in the “Dungeons” for breach of the Sabbath. Her cell was so small that she couldn’t stand upright. It was accessible to the street, however, so James Whittaker, one of her followers, fed her wine and milk through a pipe stem he stuck in the keyhole.

One Saturday evening James reported seeing a vision. He claimed he saw a large tree in America, where every leaf seemed like a burning torch. The meaning of the vision was clear to Mother Ann. She believed that the second Shakers church would be established in America.

Immediately she sent John Hocknell, another follower, to the seaport of Liverpool to secure passage to America for a small party of Shakers. When he returned, John warned Mother Ann: “People are saying the ship, the Mariah, will sink.”

Ann answered, “God will not condemn it when we are in it.”

John Hocknell had saved enough money from his shop to pay expenses for the whole group. On May 10, 1774, the party of nine Shakers, consisting of Ann; her husband, Abraham; her brother William Lee; her niece Nancy Lee; Mary Partington; James Whittaker; James Shepherd; and John Hocknell and his son Richard sailed aboard the Mariah, bound for New York.

Soon after setting sail, the Shakers began to praise God by singing and dancing on deck. When the captain threatened to throw them overboard, Mother Ann told her followers it was better to listen to God than to man. While they continued to worship, a sudden storm blew up, and a loosened board caused the ship to spring a leak. The water started gaining on them, for it couldn’t be pumped out quickly enough.

Ann told them to trust in God, for an angel had appeared before her with the promise of their safety. Suddenly a great wave came and closed the displaced board. Soon the pumps were stopped. After that the captain allowed the Shakers to worship freely.

On August 6, 1774, 11 weeks after leaving England, the Mariah and its passengers arrived safely in New York. The Shakers walked up Broadway until Ann led them into a side street. It was a warm Sunday afternoon, and a few people were sitting on the front steps of their house when Ann confronted them. “I am commissioned of God to preach the everlasting Gospel to America . . . , and an Angel commanded me to come to this house, and to make a home for me and my people,” she said.

The Shakers were given temporary refuge until they obtained jobs. Ann stayed on to work as a housemaid, while the others scattered. Abraham took to drinking and deserted his wife. Alone in an unheated room, she became ill and unable to work.

What Mother Ann wanted most was to spread the message and to worship with her followers. One day she learned from some Quakers that it was possible to obtain cheap land about 100 miles north of the city. John Hocknell, James Whittaker, and William Lee traveled up the Hudson River to investigate.

The Shaker men took a long-term lease on some land, a low, swampy wilderness cut off from civilization, about seven miles northwest of Albany. It took them a year to clear a portion of the land and build a simple log shelter. They built a room at ground level for the “sisters” and attic space for the “brethren.” Finally, in the late 1770s, Ann and her group moved to their land to start the first Shaker settlement in America.

The Indians had called the territory Niskayuna, which meant “maize land.” Later it was renamed Watervliet. Mother Ann said, “Put your hands to work and your hearts to God.” Slowly the Shaker settlers tamed the wilderness. They cleared trees and dug ditches to drain the fields. Some practiced their own trades, such as blacksmithing, in Albany in the winter. In a few years the colony at Niskayuna built simple but comfortable homes and barns. They raised good crops and began working on arts and crafts.

In 1779 a religious revival took place in Lebanon Valley, New York, about 30 miles from the colony. Some of the leaders visited the Shakers and joined them. They came from Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Maine. Some went home and formed Shaker colonies of their own.

Violent persecutions followed when Mother Ann and others embarked on missionary tours. In Petersham, Massachusetts, a crowd dragged her from her horse, threw her into a sleigh, and tore her clothes. She and some of the elders were accused of being British spies and were savagely abused. They were put into prison in Albany. Then Ann was separated from her followers and sent to Poughkeepsie, New York.

From her cell she could call out to passersby. Word was spread that a poor woman was being held because of her religion. She was then taken to a private home, where she conducted worship services. Some of the townspeople protested. They dressed like Indians and threw little bags of gunpowder through the windows and down the chimney into the fireplace.

After that, things quieted down. Five months later Mother Ann was released from prison by Governor George Clinton. She arrived, in a state of exhaustion, back at Watervliet two years and three months after having left. Eight Shaker communities had resulted from her mission in New England.

All that Mother Ann had undergone probably hastened her death, which took place on September 8, 1784, at the age of 48. Her brother William had died on July 21 of the same year. Ten years in America had taken its toll, but Ann’s mission had been accomplished. Shakerism was well established in the East and later spread to Kentucky, Indiana, and Ohio.

The Shaker influence peaked before the Civil War, and then their numbers lessened. There are now very few Shakers, but Ann Lee, a woman of great faith, left her mark on the religious history of the United States.