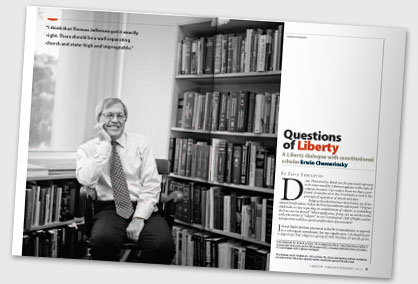

Questions of Liberty

David Pendleton January/February 2011

Dean Chemerinsky, thank you for graciously agreeing to be interviewed for Liberty magazine on the topic of religious freedom. Our readers know we share a profound commitment to the Constitution and to the principle of separation of church and state.

Religious freedom has been described as one of our nation’s first freedoms. In fact, the First Amendment reads in part: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” What significance, if any, can we ascribe to the early placement of “religion” in our Constitution’s Bill of Rights and its juxtaposition with free speech and freedom of association?

I do not think that their placement in the First Amendment, as opposed to a subsequent amendment, has any significance. I do think that it is important that religion is grouped with freedom of speech, press, assembly, and petitioning government for redress of grievances. All of these are ultimately about freedom of conscience. All are about the ability to have freedom to follow and express this freedom of conscience in various ways.

We nearly did not have a Bill of Rights because at least the early James Madison thought it unnecessary as the national government was of limited and enumerated powers. Is the lesson that structural safeguards require express substantive guarantees to protect our liberties?

The Constitution as drafted did not include a Bill of Rights. The framers thought it unnecessary because they saw the structure of the government—a government of limited powers with checks and balances—sufficient to protect liberties. They feared that they could not list all rights and that enumerating some would be taken to deny the existence of others. But several states insisted on a Bill of Rights. It is difficult to imagine the United States Constitution without an assurance of due process, or protection from unreasonable searches and seizures, or safeguards for speech and religion.

The core protection for religious liberty is found in the free exercise clause and establishment clause. Particularly memorable has been Thomas Jefferson’s phrase regarding a “wall of separation of church and state.”What should an American know about these two clauses and this phrase of Jefferson’s that first appeared in private correspondence but was later cited by the Supreme Court?

The free exercise and establishment clauses are largely complementary. If the government establishes a religion, there is inevitable coercion to participate. If there is no free exercise of religion, it is the state establishing an orthodoxy of faith.

I think that Thomas Jefferson got it exactly right. There should be a wall separating church and state: high and impregnable. This means that the government should be secular; the place for religion is in the nongovernment realm, in our homes and places of worship and daily lives. The free exercise clause then protects the ability to practice (or not practice) religion as one chooses.

In 1940 the Supreme Court said in Cantwell v. Connecticut that the freedom to believe is absolute. More recently Justice Scalia has written that a ban against casting of statues that are to be used for worship purposes, or to forbid the bowing down to a golden calf, would be unconstitutional. Yet in his Smith decision he precluded certain Native Americans from practicing a key religious belief. If religious liberty must allow some freedom to act–because merely permitting entertaining a belief in the privacy of one’s mind is a rather inadequate freedom – what are the limits to religious faith and practice?

Prior to Employment Division v. Smith (1990), the government could burden religion only if its actions were necessary to achieve a compelling government interest. Freedom of religion, of course, was not absolute. People could not inflict harm to others based on religion. But the government would need a compelling reason and no less restrictive alternative to significantly burden religion.

Employment Division v. Smith changed this. Now the free exercise clause cannot be used to challenge a neutral law of general applicability no matter how much it burdens religion. The law will be upheld so long as it was not motivated by a desire to interfere with religion and so long as it applied to everyone. This makes it far more difficult to successfully challenge laws as violating the free exercise clause.

Erwin Chemerinsky speaking at the William & Mary School of Law in September 2007.

Erwin Chemerinsky speaking at the William & Mary School of Law in September 2007.

For those of us who are not constitutional scholars, sometimes it is challenging to discern how a law might apply to faith. Looking back over the past years, we see that the Amish, for example, prevailed when it comes to seeking an exemption for their kids not to have to attend school beyond a certain age, but the Amish lost when it came to exemptions from Social Security. A Seventh-day Adventist woman whose faith precluded her from working on her Saturday Sabbath was entitled to unemployment benefits when fired, but the Court struck down Connecticut’s law prohibiting employers from firing workers who refused to work on their Sabbath. An Orthodox Jewish U.S. Air Force officer lost when he sought an exemption to allow him to wear a yarmulke when in uniform. Lumber-hauling trucks are permitted to drive across land sacred to Native Americans. What are the unifying principles that make sense of this?

Inevitably, in dealing with free exercise of religion, and other constitutional rights, there has to be a balancing test. How that balancing is done very much depends on the justices. The Court, for example, thought that there was a sufficient government interest to justify requiring Amish individuals to have Social Security numbers, but not to mandate that Amish 15- and 16-year-olds attend school.

This is not unique to free exercise. Constitutional law frequently involves these kinds of balances to be struck by the justices.

Now, the First Amendment is not the only constitutional provision dealing with religion. Article VI, section 2 expressly prohibits the government from inquiring into a person’s religious beliefs as a condition of federal office. How would you answer those who worry that allowing clergy in elective office risks entanglement of church and state?

But to exclude clergy from elective office is impermissible hostility to religion. The protection against impermissible entanglement is a robust establishment clause.

When the establishment and free exercise clauses were ratified they applied only to the federal/national government, and in fact there were state-established churches at the time. Subsequently these clauses were applied to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment per the Incorporation Doctrine, a manifestation of the “living constitution.” Some fear this gives too much power to the courts. Are such fears justified?

No, such fears are not justified. When the Bill of Rights was adopted these rights were deemed to apply only to the federal government. It was only after the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868 and really only in the twentieth century that the Bill of Rights was applied to the states. But few today question the decisions applying the Bill of Rights to the states. Indeed, it is hard to fathom a Constitution where freedom of speech and free exercise of religion and the prohibition of unreasonable searches and seizures did not apply to state and local governments. This is a powerful reason that a living constitution is essential.

Regarding intelligent design in public school curricula and placement on government property of crèches, menorahs, and the Ten Commandments, some say that the Supreme Court in deciding these cases has forgotten or weakened the free exercise clause. Others say the establishment clause required the outcome. Are the clauses in tension? Is one clause primary and the other secondary?

The free exercise clause does not require government endorsement of religion in the form of teaching of religious theories of the origin of human life or religious symbols on government property. These limits on government support for religion in no way limit or interfere with the ability of people to practice religion in their homes and places of worship however they choose.

You have been known to describe the recent Supreme Court as the Kennedy Court. What do you mean by this—and what does it mean for the future of the free exercise clause and establishment clause?

I think that there now are five justices—Roberts, Scalia, Kennedy, Thomas, and Alito—who want to dramatically change the law of the establishment clause. They want to allow much more government support for religion and much more religious involvement with government. Their view is that the government violates the establishment clause only if it literally creates a church or coerces religious participation. This will be a radical change in the law and we are likely to see it soon.