Stand Fast

Paul D. Simmons July/August 2003

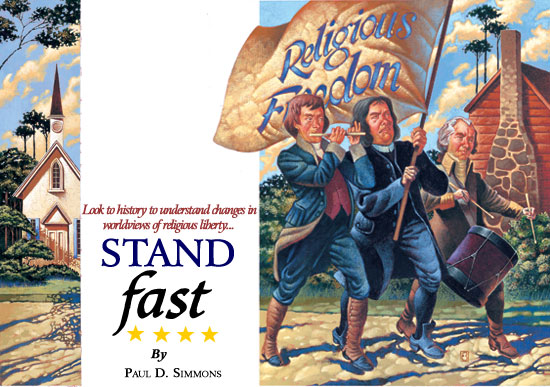

Illustrations by Ralph Butler

The United States of America has long been a marvel in the eyes of the world for its successful experiment in religious liberty. The First Amendment has often been copied but seldom implemented as successfully as in this new world. While Americans take pride in our history of preserving such freedoms, we should never take them for granted. A brief history of religious liberty is a reminder of the tortured story of this treasured heritage. In understanding the intent and content of the First Amendment two points of reference stand out. First, the Inquisition, a 600-year war against religious dissenters that spread from Italy to the Netherlands. Pope Innocent III began a coordinated policy of inquisition for heresy. An enthusiasm for genuine piety and orthodox belief transmuted into a zeal for persecuting dissenters and ended by executing those who would not recant. The frenzy was fueled by Thomas Aquinas' dictum that heresy is a sin that merits excommunication and death—expanding Augustine's notion that false belief should meet "righteous persecution"

conducted with secular assistance. The system was deeply corrupted by self-interest and hypocrisy. Zealotry was rewarded with confiscated property, the promise of absolution, and promotion to places of prominence. From 1184 to 1826 dissenters and unbelievers, Baptists, Jews, and deists, were imprisoned, tortured, or burned at the stake. The last victim of the Inquisition seems to have been a deist schoolmaster, who was hanged in 1826. The era did not end officially, however, until the Spanish Constitution embraced an edict of toleration in 1869.

The second story is that of dissent in England and the oppressive tactics of Archbishop William Laud in enforcing the Articles of Conformity. King James I (1603-1625), horrified by the notion of religious liberty, declared, "It is the chiefest of kingly duties . . . to settle affairs of religion." When Thomas Helwys (1611), a Baptist, wrote saying that religious belief was none of the king's business, he was imprisoned at Newgate for the rest of his life. King Charles I (1625-1649) was inaugurated as "Supreme Governor of the Church." He led a violent persecution of dissenters, saying that all subjects were to be "in uniform profession" of the Church of England. The least differences from the Articles of Conformity were forbidden on pain of death.

Separatists, Puritans, Baptists, and other dissenters were subjected to persecution, including the loss of properties, whippings, and imprisonments. Physical maiming was also meted out—such cruelties as cutting off ears and slitting the nose. Even today many remember John Bunyan, a Baptist, who was imprisoned for 14 years for insisting on freedom of conscience in religious matters. An official church and its "act of intolerance" forbade any religious witness not approved by the Crown.

Little wonder that Puritans and Pilgrims fled to the New World. The Puritans implemented a new dream following the sort of theocratic vision that guided Geneva under John Calvin. They wanted religious liberty for themselves, but not for others. The Massachusetts Bay Colony was a hotbed of religious fanaticism that fiercely prosecuted dissenters and destroyed witches, reflecting many of the same tactics and excesses of their European past. But religious liberty had its advocates. Nearly a century after the death of Bunyan, in the Commonwealth of Virginia, a dramatic conversation took place between neighbors in Orange County. They were James Madison and John Leland. The subject was the established church of Virginia. The Baptists felt it unjust that they should be taxed to pay the salaries of Anglican priests and support the work of a church with whom they had strong religious differences.

A political agreement was apparently reached. Leland would withdraw his opposition to Madison, and Baptists would support the Jefferson-Madison efforts to disestablish religion in Virginia, and to assure religious liberty in the Constitutional Congress. Virginia approved a declaration of religious liberty in January 1786, and the Constitutional Congress followed suit under the leadership of Madison and Jefferson, who (later) spoke eloquently of a "wall of separation" that should exist between church and state.

A Free Church in a Free State

From the blood, tears, ashes, and prayers of those who had suffered so brutally for insisting on liberties of the mind and conscience, a new era came into being.

A new relation between church and state, without parallel in other countries of the world, was being implemented.

States slowly but wisely adopted the new amendment. Connecticut dropped its established church in 1818 and Massachusetts in 1833. The new vision taking hold in the community of states was to ensure that ancient patterns of oppression and false alliances would not be repeated in America.

Three patterns were clearly rejected.

First, in this republic there would be no dominant church over state. The Holy Roman Empire was dead. The evil collusion of religion and government would not extend into this country "conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all [people] are created equal," as Lincoln so eloquently said.

Second, gone were the days when the king could control a subservient church. King Henry VIII had only reversed the political alliance he saw in Rome. With Thomas Hobbes he felt the state should control the church, which severely restricted the liberties of dissenters.

Third, the theocratic vision of Puritan New England was also rejected. In America citizenship would in no way be linked to orthodox religious belief, practice, or church membership.

A new vision had become a reality—a free church in a free state. An amendment was added to the Constitution attempting to assure the integrity of each without the encroachments or controls of the other: "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof."

This simple but profoundly important amendment was intended to guarantee that:

- No religious group would be recognized as the established, favored, or official church for the nation.

- Congress would not meddle in religious or doctrinal disputes among the various groups as had the ancient councils.

- The various religious groups would be free to support their missions by their own constituents, but government funds would not be used to support religious causes or institutions.

- No religious dogma would be made law for everyone, nor would anyone be forced to live by any particular doctrine.

- Dissent on religious opinion could not become the basis of criminal prosecution.

- Government would not interfere with religious exercises. It would occupy itself with maintaining domestic tranquillity and defending the country against enemies both domestic and foreign.

- The people would be free to be religious or not religious. Religion was to be purely voluntary. Government could use its coercive powers only for the interests of state; it was not to be a religious body. Prayer and doctrine were not to be found in its jurisdiction.

A new relation between religion and politics was established by this amendment. The task of government was to preserve and protect this arrangement of religious and secular affairs. The courts were appointed guardians to assure strict adherence to what Jefferson called a "wall of separation" that should exist between the powers of church and those of the state. Congress was carefully restricted in the types of law that could be imposed upon the citizenry—no dogma could be camouflaged as law, even under the guise of majority rule.

Religious liberty was given birth. A witness was raised to all the world that drawing a firm line between the interests of government and those of institutional religion would best protect the uniqueness and value of each. Religious groups such as the Baptists and Methodists, and free thinkers such as Madison and Jefferson, believed that liberty in religion would better assure the freedoms of government and civil coexistence in a pluralistic society.

Freedom of Religion meant that government could not coerce people of faith to conform to regulations in doctrine, morals, or polity not of their church's own making.

Freedom for Religion meant that religious leaders were free to speak their mind, even criticizing policies and practices of government, without fear of punishment or retribution.

Freedom from Religion candidly recognized that even atheists have rights of conscience in a free and pluralistic society. Public policy would also reflect the rights of those who professed no religion at all.

Religious Freedom—A Fragile Possession

A social contract of toleration, respect, and acceptance of various religious traditions and doctrinal persuasions was fashioned and accepted by all groups consenting to the new Constitution.

The covenant was dearly won. But religious liberty and the tolerance it requires between and among the various faith traditions was and is a fragile possession. Its protections lie in the First Amendment, an informed Supreme Court and judicial system, a friendly and supportive Congress and executive branch of government, and the mutual agreements of the various sects, religions, and denominations in America.

Now, more than 200 years after that precarious agreement, we are testing whether it can survive a new assault and ensure that our children will enjoy the liberties assured by this fragile vision. New alliances have emerged that threaten the guarantees at the heart of the First Amendment. Religious liberty is under fire; the wall of separation seems about to fall away.

The "free church in a free state" idea has always been a minority opinion in America. Now the church-over-staters, the state-over-churchers, Puritan theocrats, and a variety of politicians who care little for religion but a great deal about power are working fervently to erase the protections and privileges of separating church from state.

Evangelical Christians, whose roots are in Puritan New England, are trying to exert newly organized political power. Many of them want America to be a theocracy with civil and religious morality intertwined. They are trying to impose their moral and doctrinal opinions on everyone.

The Puritan preacher was a stern moralist who believed that mere mortals could never decide rightly before God. Judging the laity and ordering the magistrate to pass laws to serve righteousness and assure doctrinal fidelity was the Puritan preacher's perceived role.

Religious Freedoms Under Fire

The long line from Cotton Mather and Jonathan Edwards now includes contemporary religious leaders who seek political power "in the name of God."

The effort to blend religion and politics is precisely what drove Roger Williams out of Massachusetts and into the wilderness with the Indians during the frigid winter of 1635. The land he purchased became the Colony of Rhode Island, the first great experiment in religious liberty among the Colonies. No matter whether one was Catholic, Jew, Protestant, Muslim, or an atheist; one was free to follow the dictates of one's own conscience. The First Amendment to the Constitution followed the Rhode Island example.

The theocrats among us would still suppress dissent, control our thoughts and freedom of expression, muzzle our minds, and ban our books. Oppressive religions we have with us always; they live to kill the freedom of the human spirit in the name of "Christian orthodoxy." Soul competence and freedom of conscience have never been tenets of Puritan theology. Politically zealous evangelicals are putting a battering ram against the wall of separation. A number of conservative Christians have organized into a powerful right-wing political movement, supporting ultraconservative causes and political leaders. The fiery rhetoric of "culture wars" and the belligerence of an absolutist mind-set typify the style and strategy of the Religious Right.

- Tuition tax credits and school vouchers are sought under the guise of "choice" and "quality education" but would in effect provide public funding for sectarian education.

- Efforts persist to pass an amendment to the Constitution declaring that America is a Christian nation.

- Requirements for mandated prayer in the public schools continue to be proposed at both state and national levels.

The Constitution assures us that Congress should make no law respecting an establishment of religion. Prayer is the business of the church; it is entirely voluntary and should not be used to badger or harass people with different religious perspectives. The coercive arm of government does not belong in the religious arena.

William Bennett, former secretary of education and now active in the Religious Right, argues that "freedom of religion is being destroyed" by those who oppose government-mandated prayers and tuition tax credits. His "values in education" agenda is strongly committed to breaking the wall of separation between church and state. He believes religion will not survive if government does not subsidize the educational and missionary enterprises of various churches. His perspective is totally contrary to the evidence—religion thrives best when it is free from government entanglement. Further, Bennett contradicts the observations of James Madison, who noted how a religion-government alliance works to the detriment of each.

Religion in America has never depended, does not now depend, and will not in the future depend upon government subsidies to survive. Only those theocrats and church-over-staters who believe government should finance religious affairs believe otherwise. Their ideology, self-interest, and tradition seem clearly evident. The separation of church and state is not a secular idea. It was given birth and is strongly supported by those of the free church tradition.

The Religious Right has also engaged in harsh criticisms of the Supreme Court in recent years in efforts to further their cause. These are thinly disguised attacks on religious liberty itself. Former attorney general Edwin Meese advocated government-mandated prayer in good theocratic fashion, and screened candidates for federal judgeships who met his religious "litmus test." Judge Roy Moore, of Alabama, a Meese choice, posted the Ten Commandments in his courtroom in violation of Supreme Court decisions. He was joined in his crusade by then-governor Fob James, who threatened to call out the National Guard if anyone attempted to remove the Decalogue from the courtroom.

Bennett and others rightly say that the Judeo-Christian tradition has made a vital contribution to American government. But that contribution is best seen and experienced in one word—freedom. That includes freedom from coercion by government in religious matters; freedom from doctrinal orthodoxy imposed by legislative fiat; and freedom from state financial support for religious enterprises.

Politics and the First Amendment

The political process is both a major source of the damage to the wall and the hope that it might be preserved. Needing coalitions of voter groups tempts politicians to sacrifice a precious heritage for a mass of votes. Promising money for religious projects is another way to pander to various factions. Such expediency compromises principle for power.

The claim that "the Constitution guarantees freedom of, not freedom from, religion" was often heard in the 2000 presidential election campaign, by both Democratic and Republican candidates for president. This clever rhetoric betrays either a serious gap in knowledge or cynical political opportunism. James Madison once defended the rights of unbelievers by saying that "we cannot deny an equal freedom to those whose minds have not yielded to the evidence which has convinced us."

The cynical manipulation of the public among politicians is widespread. In Kentucky a candidate for the state senate based his campaign on his desire to post the Ten Commandments in every school. His pitch was that those who opposed the plan believed that the Ten Commandments were bad for schoolchildren! Such misrepresentations generate anger in the electorate and support for antiseparationist legislators.

James Madison refused such collusions, arguing it would be "a precedent for giving to religious societies as such a legal agency in carrying into effect a public and civil duty." He thought such actions would be incongruous, since freedom and voluntariness would be lost. Government operates by power; it is not an advisory agency. Madison felt that "every new and successful example therefore of a perfect separation between ecclesiastical and civil matters, is of importance."

Bush's nominee for U.S. Attorney General, John Ashcroft, is an avowed enemy of the wall of separation. On such issues as abortion he shows little insight into the problem of imposing a faith-based metaphysic upon all citizens through public policy that would forbid or severely restrict a woman's procreative choices. But he is enthusiastic about religion and the prospect that the coercive arm of government might make us a more moral people. Like Meese, he will be inclined to appoint like-minded federal judges who care more for their brand of conservative religion than for protecting all Americans' First Amendment rights.

All political leaders need a good course in American history exposure to the stories and thoughts of Roger Williams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and a host of others whose lives and fortunes were put on the line for religious liberties. The text could be The Federalist Papers. Politicians should also learn from those who suffered, bled, and died to win the liberties assured by the First Amendment. They should learn from the horrible mistakes of the Inquisition and Puritan New England. They need to hear the voices from the graves of those who were imprisoned, tortured, or burned at the stake. They should know the stories of John Bunyan,

Thomas Helwys, John Leland, Isaac Backus, and countless others!

Those who suffered for religious liberty did not need, and we do not want, kings or parliaments, presidents or Congress to require us to pray. Politicians need the tempering judgments of tolerance across religious lines in a pluralistic society. Their task is to protect both believers and unbelievers from actions or social policies that impose hindrances to the free exercise of conscience for all people. Their challenge is to overcome personal prejudice and the arrogant use of political power. When those in office embrace the stern lessons of voluntarism in religion, they will strengthen, not batter, the wall embedded in the First Amendment.

Until they do, those determined heirs of Williams, Leland, Jefferson, and Madison must band together, not only to pray for Congress, the president, and the Supreme Court, but to insist that they respect and protect our rights to religious liberty.

Thomas Jefferson once vowed to keep eternal vigilance and wage constant war against every tyranny over the human mind. He was speaking of misguided religion that attempted to exploit every political advantage over others. Our spirits, our consciences, and our minds are in danger from an old tyranny in a new disguise.

The great irony on the current scene is that those politicians and religious leaders speaking loudest about the danger to religious expression are proving themselves a threat to that precious freedom. James Madison rightly warned Americans that "it is proper to take alarm at the first experiment on our liberties."

Misguided politicians and the demagogic theocrats must not rule the day. The time has come to say no to further assaults on the wall of separation between church and state. With our cards and letters, our telephone calls, our personal influence, and the process of the ballot box, we should cast our vote for keeping a strong wall of separation between church and state. And there is Scripture for this. Hear the Word of God proclaimed by those who died for the right to be heard by presidents and parishioners alike: "For freedom Christ has set us free; stand fast therefore, and do not submit again to a yoke of slavery" (Galatians 5:1, RSV). *

____________

Paul D. Simmons is clinical professor in the Department of Family and Comnnunity Medicine, University of Louisville School of Medicine. He is also adjunct professor at the Louisville Prebyterian Seminary.

____________

* Bible Texts credited to RSV are from the Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright