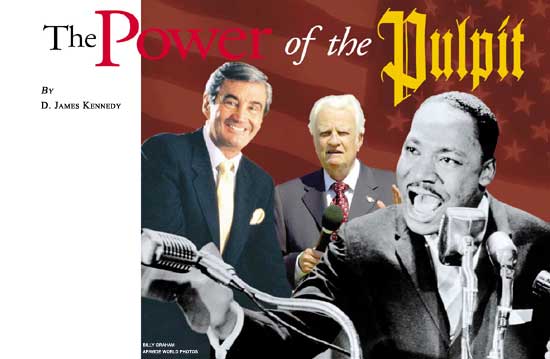

The Power of the Pulpit

D. James Kennedy July/August 2004

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

In the summer of 1954 Senator Lyndon B. Johnson had a problem: what to do about powerful anti-Communist organizations that threatened his Senate reelection. The answer proved amazingly simple.

On July 2, as the Senate considered a bill to revise the tax code, Johnson offered a floor amendment to ban all nonprofit groups from engaging in political activity. Without hearings or debate—without so much as a speech by him to explain and justify his far-reaching measure—the Senate passed the Johnson amendment on a voice vote.

Johnson targeted his political opponents, but churches were caught up in the ban. In just minutes and without debate, churches, for reasons that had nothing to do with the separation of church and state, were stripped of their liberty to participate in America's political life.

That will change if the Houses of Worship Free Speech Restoration Act, introduced by Representative Walter Jones, and cosponsored by 165 other members, becomes law. Jones's bill will reverse Johnson's ban and return the protection of the First Amendment to America's churches, synagogues, and mosques.*

It will restore to churches a freedom and role that dates to America's infancy. Nineteenth-century historian John Wingate Thornton said that "in a very great degree, to the pulpit, the Puritan pulpit, we owe the moral force which won our independence."

The British would likely agree. Disgusted at the black-robed clergy's prominent role in stirring the colonies to fight, the redcoats called them the "black regiment." The governor of Massachusetts complained that Calvinist pulpits were "filled with such dark covered expressions and the people are led to think they may lawfully resist the King's troops as any foreign enemy," Marvin Olasky reports in Fighting for Liberty and Virtue.

Politician and writer Horace Walpole declared in Parliament that "Cousin America has run off with a Presbyterian parson." Walpole was most likely referring to John Witherspoon, a Presbyterian minister, president of Princeton, and a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Witherspoon, who was accused of turning his college into a "seminary of sedition," was the most important "political parson" of the Revolutionary period, according to the Library of Congress.

He was so persuasive, Olasky writes, that a British officer called him a "political firebrand, who perhaps had not a less share in the Revolution than Washington himself. He poisons the minds of his young students and through them the continent."

But during the Revolutionary era it was the graduates of Yale and Harvard, serving in churches across New England, who laid out the theology of resistance that made war with Britain inevitable. "The ideology for revolution had been expounded for 150 years in New England's pulpits," Ben Hart wrote in Faith and Freedom: The Christian Roots of American Liberty. Back then the pulpit was the unchallenged focal point of public communication. The sermon was so powerful in shaping the culture "that even television pales in comparison," according to Harry Stout, author of The New England Soul.

When General Gage sought to silence the incendiary messages sounding forth from New England's "black regiment," one member of the clergy, William Gordon, declared in defiance that "there are special times and seasons when [the minister] may treat of politics." To do otherwise was not possible for New England's ministers, who, as God's watchmen, had been faithfully applying God's Word to every area of life since the first generation arrived in Massachusetts.

"Watchmen upon the walls must not hold their peace," the Reverend Moses Parsons told the Massachusetts Council and House of Representatives in his 1772 election sermon. "They must cry and not spare, must reprove for what is amiss, and warn when danger is approaching."

In the mid-nineteenth century, evangelical Christians were primary agents in shaping American political culture, according to Richard Carwardine, author of Evangelicals and Politics in Antebellum America. "Political sermons, triumphalist and doom laden, redolent with biblical imagery and theological terminology, were a feature of the age," he writes.

One minister distilled the question before voters in the 1856 election as a contest pitting "truth and falsehood, liberty and tyranny, light and darkness, holiness and sin . . . the two great armies of the battlefield of the universe, each contending for victory. "

Language like that might today earn a visit from the Internal Revenue Service. It did in 1992 after the Church at Pierce Creek in Vestal, New York, placed a newspaper ad warning Christians not to vote for Bill Clinton for president. Such a vote, the ad warned in rhetoric echoing 1856, would be to commit a sin. The IRS took notice and three years later revoked the church's tax exemption.

Aggressive toward Pierce Creek, the IRS has at other times looked the other way. In 1994, for example, New York governor Mario Cuomo campaigned for reelection on a Sunday morning at the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Harlem. "Cuomo was rewarded with a long, loud round of applause and an unequivocal endorsement from the pastor," according to a Newsday report. The American Center for Law and Justice, which represented the Church at Pierce Creek, uncovered evidence at trial that the IRS knew of more than 500 instances in which candidates appeared before churches, as happened with Governor Cuomo and Bethel A.M.E., but took no action to revoke these churches' tax-exempt status.

The unequal enforcement of the existing law is just one of several reasons that scrapping the political activity ban altogether is a good idea. The political activity restriction is a blatant violation of the First Amendment, is vague and burdensome, and is a marginalizer of churches at a time when America most needs a moral compass.

The First Amendment states that "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech." Yet that is exactly what the Congress has done by silencing churches.

Nor is the political activity ban easy to obey. Not just endorsements, but voter education activities, such as voter guides that compare office seekers on issues, may violate the ban if they are perceived as partisan. Even addressing moral concerns, such as abortion, from the pulpit during an election campaign may violate the IRS rule if abortion, for example, is under debate in the campaign.

With so much uncertainty and so much at risk, silence is, regrettably, the only option for the minister who wants to ensure that the IRS does not open a file on his church. But when Caesar's demand for silence confronts the message of God's Word, ministers are forced into hard choices. That's what happened in Nazi Germany a generation ago. Many pastors submitted, and were silent. Others were not, and paid the price.

If, as has been asserted, we owe our liberties to the "moral force" of the pulpit, the censorship of that voice—for reasons that have everything to do with partisan politics and nothing to do with the separation of church and state—is a monumental mistake that should be quickly corrected. In a culture such as ours, which sometimes seems on moral life support, the voice of the church and her message of reconciliation, virtue, and hope must not be silenced.

___________________________

D. James Kennedy, Pj.D., is senior minister of Coral Ridge Presbyterian Church and president of Coral Ridge Ministries, Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

___________________________

*This article by D. James Kennedy is particularly appropriate for an issue of Liberty that focuses on the need for moral activism and the need to distinguish it from purely secular political activity. The Seventh-day Adventist Church began publishing Liberty a century ago; at that time the church was in the forefront of a moral crusade to fight the liquor traffic. Visionary church pioneer Ellen G. White argued that members had both a civic and religious responsibility to fight the battle through social change and legislation. However, she and others cautioned against "partisan," or party, political action, and emphasized, as does Tony Campolo in the article "Dealing With Babylon," that church and state are two very distinct things—and that the church can easily compromise its higher calling if it entangles itself in matters of state and politics. In a Liberty article entitled "The Quest for Power and Influence," Rabbi Gerald Zelizer gave good reasons why the legislative remedy of the Houses of Worship Free Speech Restoration Act, cited by Kennedy, is less a remedy than an unprecedented empowerment for churches to act as proxies for political parties, even as those parties are limited under campaign reform legislation. He is correct in noting that practically speaking the government seldom troubles churches that are openly political—and when it does, the penalty is usually loss of tax exemption. There is need to ensure that such actions are not punitive and used to direct the voice of the church in ways the state would like. There is no doubt of the role of the pulpit in times past to stir the public on great causes. But the real power of the clergy lies in moral persuasion, not in appropriating the tools of the state in the manner that they were wont to do before the Reformation. And the tax exemption, colored no doubt by assumptions of church privilege dating back to times before the separation of church and state was imagined by society at large, is itself an acknowledgment of the nonpolitical, spiritual nature of a church. We do need to ensure that in a post-9/11 climate we do not allow a suspicious government to muzzle any church group—Muslim, Christian, or any other. And all people of faith should be prepared to speak out on moral issues and expect their church leaders to do so.

—Editor.