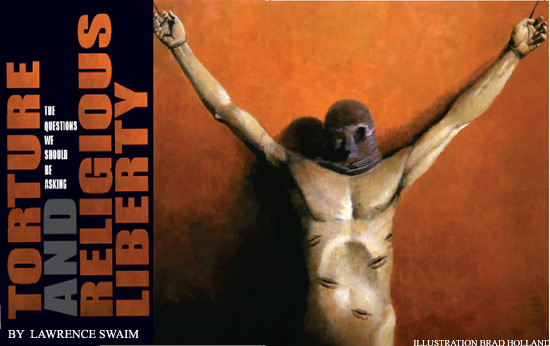

Torture and Religious Liberty

Lawrence Swaim

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Torture is a demonic outbreak of radical evil at the heart of the social contract between the individual and the state. In our time it is usually the product of religious hatred, and is typically supported by people who believe in religious war. It shouldn't surprise us, then, that those who torture would use attacks on religion to achieve their goals. But it should disturb all Americans that interrogators at the US Naval base at Guantanamo Bay are alleged to practice just such obscene forms of so-called "enhanced interrogation."

Four former detainees at Guantanamo—Shafiq Rasul, Asif Iqbal, Rhuhel Ahmed and Jamal al-Harith—are litigating in Rasul vs. Rumsfeld to hold government officials accountable for torture they endured while being held there. (All were found innocent of terrorist activity and released in 2004.) Represented by the Center for Constitutional Rights, the four British citizens first cited violations of the United States Constitution and international law (including beatings, painful shackling, interrogation at gunpoint, use of dogs, extreme temperatures, and sleep deprivation), but the court refused to consider them because they occurred in the "course of war." Allegations of deliberate attacks on religion were not so easily ignored, however, and are currently being considered by an appeals court in Washington, D.C.

The former detainees allege that they were forced to shave their beards, were systematically interrupted while praying, denied the Koran and prayer mats, made to pray with exposed genitals, and forced to watch as the Koran was thrown into a toilet bucket. Obviously, the only reason for such abuse would be to crush inmates psychologically by insulting their religion. Therefore it could, if proven, violate the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993, which seeks to protect religious expression.

The RFRA was originally passed by a broad interfaith coalition including the Conference of Catholic Bishops, National Council of Churches, American Jewish Committee, National Association of Evangelicals, the Seventh-day Adventist Church, and the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty. They came together again recently to submit friend-of-the-court briefs on behalf of the four plaintiffs.

The appeals court dwelt especially on definitions of the words person and religion as used in the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. The Justice Department argued that Guantanamo detainees might not be "persons" as defined by RFRA.

There is a bizarre quality to the alleged misconduct at Guantanamo, as though military personnel were making it up as they went along. Were U.S. personnel experimenting with religion-specific forms of torture, aiming to manipulate religious symbols and sensibilities as a form of psychological abuse? If so, Guantanamo detainees had little information that would help America catch terrorists—interrogators found only a small number of "high-value" detainees who were actually guilty of anything. Jamal al-Harith, one of the four plaintiffs, reports that he falsely confessed under torture to being an associate of Al-Qaeda, but was later cleared.

Many detainees at Guantanamo ended up there because they were soldiers or low-level functionaries sold to the Americans by Afghan warlords; at least one—still held at Guantanamo—is a journalist. Yet Donald Rumsfeld denounced detainees as the "worst of the worst." How could an American secretary of defense make such a public statement, when to do so would surely prejudice any future trial? So defined, as irredeemably dangerous, they were convenient guinea pigs for various kinds of interrogation based on religious hatred, insult, and humiliation.

Any act that causes "severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental" is considered torture under the UN Convention Against Torture. Today's state-sponsored torture tends, if it is not halted in its early stages, to become more violent, more invasive, more religion-specific, and more sexualized. It is also much more likely to cause death.

At Abu Ghraib, torture continued to be calibrated specifically to offend Muslim sensibilities. In the process it became markedly more sexualized, since military and intelligence personnel believed sexual acts were especially humiliating to Muslims. Besides being forced to engage in sexual acts that were photographed, allegations include rape of men and women (some of them filmed), sodomy with objects, beating arms and legs that were already broken, pouring acid into wounds, and forcing female inmates to strip in order to film them. At least one Iraqi died while being tortured. Yet according to the International Committee of the Red Cross, the vast majority of detainees in Abu Ghraib were innocent of any terrorism. (Most of them were apparently petty criminals, the developmentally delayed, and the mentally ill.)

Religious hatred is a theme that comes up often in torture narratives. It was testified by defendants under oath that in 2004 a young taxi driver was taken into custody in Afghanistan at a military detention center near Bagram Air Base. He was tortured over a period of 24 hours, even though the people torturing him knew that he was innocent of any crime. Every time he was struck, he would cry out "Allah!" This reportedly amused some military personnel. He was beaten as he hung from the ceiling of his cell until he died some 24 hours later. (He was one of two prisoners beaten to death at Bagram just down the hall from the commander of the detention center.)

Some Americans were ultimately prosecuted for the Bagram torture, although the majority of the estimated 27 people involved were never charged, including the commander. While low-level perpetrators of torture are often prosecuted when the abuse is discovered, most aren't, nor are higher officers usually prosecuted. Prosecution of civilian intelligence officers is practically unknown. Nor are torturers in the CIA's secret prisons held accountable; nor are those government officials who arrange for "extraordinary rendition," a process by which Muslims are sent to third-party countries to be tortured. (Those who assume that such detainees are invariably terrorists should consider the case of Maher Arar, a Canadian who was completely innocent, yet sent to Syria and tortured for ten months.) The real problem is Why are Americans torturing at all, and what gives perpetrators the idea that they can do so with impunity? The Center for Constitutional Rights coordinates the work of more than 500 pro bono lawyers representing Guantanamo detainees. In a statement to the press, Eric Lewis explained his organization's goals and legal strategy in this way: "The detainees at Guantanamo have been subject to deliberate humiliation because of the Defense Department's misguided and illegal effort to exploit their faith to break them down psychologically. . . . We hope to persuade the court of appeals that the district court was correct in finding such conduct illegal under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, a statute meant to ensure that the government respects the religious faith[s] of all people."

This is a profound moral challenge for many American Christians. Torture is never justified and is an offense against God as well as international law. If putting the state above God is a particularly degraded form of idolatry, torture is its evil sacrament. When Nero devised increasingly cruel ways to publicly torment Christians to death in the first century after Christ, he was engaging in state terrorism based on a perceived religious enemy. Nero's intent was to demonstrate the power of a cruel imperial state—and his own status as a "divine" being—in the eyes of the traumatized Roman populace, while punishing Christians for their upstart faith.

It is the sacred responsibility of every true Christian—and every American patriot—to witness to freedom of conscience in religious matters. When American military and intelligence agencies use religious humiliation as a form of torture, they are engaging in a brutal and unconscionable form of religious persecution by the state. And it is based on religious hatreds so volatile that it can quickly get out of hand, resulting in homicide, aggravated sexual

assaults, and other unspeakable crimes.

So why don't we speak out more passionately against torture?

One reason is denial—we don't want to know about unpleasant things, especially when our own government does them. A second reason is a major infusion of religious nationalism into American Christianity. One manifestation of this is the rise of the Religious Right, which mistakenly assumes that the spiritual values of Christianity can be enforced by the state.

Another thing that stops Christians from speaking out against torture more forcefully is a subtle but idolatrous addiction to middle-class respectability. This was a conceit that entered Christianity around the time of the Reformation, often accompanied by a belief that God would reward His saints on earth with material goods. Christianity gradually became associated in the minds of many believers with economic success—if only one didn't rock the boat, if only one went along with the prevailing beliefs of the day, one could have a comfortable and affluent life.

To worship respectability means never to criticize the government, the military, or even the American definition of success as power and money. But an authentic Christianity must be a robust counter-cultural force and must sometimes take unpopular positions. It must be able to stand up to the scorn of elitist political and cultural fashions, and sometimes even oppose the complacent majority.

If we are not willing to witness against systemic evil in government—or against the dominant cultural paradigms in society at large, when they are wrong—we can offer no alternative to the demonic forces of nationalism, racism, materialism, and power worship. In the twentieth century this self-serving reticence resulted in the moral collapse of Christianity in Germany under Hitler and even gave aid and comfort to the genocidaires of the killing fields of Rwanda.

But isn't that politics?

No, because politics is about getting power, whereas Jesus' message is about changing the nature of power—from hate to love, from death to life.

We must be intimately familiar with the political discourse of our time, in order to best discern if and when the state is breaking God's laws or inappropriately intruding in matters of faith. Those who are afraid to witness for religious pluralism and social justice for unpopular religious minorities would probably not recognize Jesus if He returned.

There seems little doubt today that powerful forces are once again pushing us toward religious war, and those same forces sometimes attempt to justify torture as necessary to fight that war. To be sure, terrorists who murder civilians in the name of religion are despicable—but that goes for Christians who justify state terrorism, as well. Our advocacy for religious liberty must demand accountability where the treatment of religious minorities by the state is concerned. If we cannot witness for the rule of law in that critical area, all the fine words we write and utter on behalf of religious liberty will mean exactly nothing.

This article is a longer version of a column that appeared in Southern California InFocus, California's largest Muslim newspaper, and appears here with their permission. Lawrence Swaim is the executive director of the Interfaith Freedom Foundation. He taught for eight years at Pacific Union College, and his academic specialties are American studies and American literature.