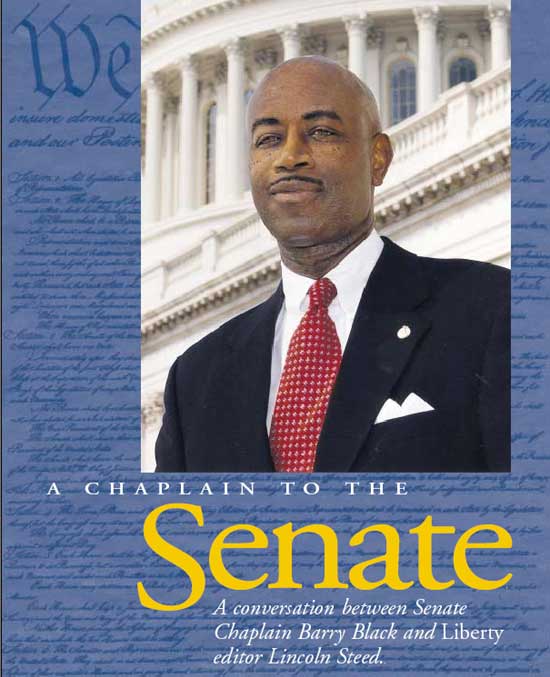

A Chaplain to the Senate

Lincoln E. Steed July/August 2004

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Editor: Did it ever cross your mind that you might one day be chaplain of the U.S. Senate?

Black: I never thought about being the Senate chaplain. One of my favorite Bible verses is Ephesians 3:20, which says that God is able to do exceedingly abundantly above all that we can ask or imagine according to His power working in us. So I expected pleasant surprises in my life, and being invited to be the Senate chaplain has certainly been one such surprise.

Editor: What is your personal mission in this post? What do you want to accomplish as you minister to the spiritual needs of this special community?

Black: I see myself as a pastor to some 6,000 plus people. I see myself primarily as what Paul described in 1 Corinthians 4:1, 2, as a servant of Christ and a steward of the mysteries of God. For me stewardship involves a wonderful experience of growing up in the Seventh-day Adventist Church. It involves having had the privilege of matriculating in church schools from grade 1 through seminary so that I can bring the harvest of theological insights, pastoral sensitivity, communication skills, and interpersonal relationship skills into this venue. I am very excited about this challenge.

Editor: It is obvious that this isn't just about projecting religion—you are getting to know people in a very personal way.

Black: I believe in an incarnational ministry. I think that is why Jesus became a human being. I don't think that you can begin to be effective until you listen in order to learn, before you seek, to lead.

Editor: Very good. Now, you have referred to the story of Daniel in the corridors of world power in his time, and I do think that there is a very good analogy to be made. Daniel served several different administrations—serving leaders with obviously different religious views. How do you relate to that challenge in today's political scene? Obviously not everybody here is a practicing Christian. Perhaps there are people of no faith. Certainly there are people of the Jewish faith; there could be Buddhists, and one day even Muslims.

Black: There are probably people who haven't declared what their religious faith is. When I was in the Navy, the largest group statistically was the "no preference" group, which was simply made up of people who said, "I don't want you to know who I am or what I am." I am sure that there are Muslims and other religious traditions on Capitol Hill. Based upon my military experience, I would be almost certain of that fact. The central draw for the diversity among Christians is Jesus, and we've learned that we have far more in common than we have in terms of differences. In the participation of the five Bible studies and in the prayer breakfast, I have sensed a tremendous unity. I have been pleasantly surprised at the significant percentage of people of faith on Capitol Hill. So it has really been a very smooth transition. Also, after providing ministry in a pluralistic setting of religious diversity for 27 years, this new setting is comfortable for me.

Black: That would be more of a challenge for someone who was a pastor, who had very strong denominational boundaries. When you have been a military chaplain, accustomed to asking "What are we doing for our Islamic personnel? What are we doing for our Buddhist personnel? What are we doing for our Hindu personnel? What are we doing for our Jewish personnel?" as well as "What are we doing for our Christian personnel?" you speak inclusion as a native tongue and not with an accent.

Editor: Sounds as though you are a good fit for a very challenging role.

Black: During the interview for this position I made the point to the selection committee that you can buy a suit off the rack or you can buy tailor-made. That when you select a pastor from a specific congregation, as the Senate has done for my last five predecessors, you basically are getting someone with a specific denominational focus who must learn the language of inclusion. And they will always to some extent speak that language with an accent. When, however, you get an individual who has been involved from his youth in inclusive ministry, you get someone who speaks inclusion as his or her native tongue. On the one hand you've got off-the-rack, and if you've got the right physique, it looks pretty good. But tailor-made is always better.

Editor: Your military chaplaincy background would indeed seem a perfect fit for this assignment. There is a question that I have to ask you, one I am sure that you have thought through before. Liberty magazine has always stood for the principle of the separation of church and state. It's not a unique view, I mean, it is explicit in the First Amendment. There is much discussion, of late, on many fronts, about how to maintain that separation. The Supreme Court justices have commented on some of the public aspects of religion—such as your role as Senate chaplain—and they have labeled most of them as "ceremonial deism." In other words, cultural symbols that in themselves don't really cross this line of separation in a dangerous way. I think most people have respect for the faith context in which this country was established and have seen how it has worked favorably for the safety of all religious prerogatives. But how about this office you now fill: how can it operate effectively without further crossing that line of separation?

Editor: Obviously as Christians . . . as Seventh-day Adventists . . . you and I are very comfortable with that. Unfortunately, there are some in this country that are using the First Amendment and a skewed view of history to drive religion in general, not just Christianity, from the public view.

Black: It is isogetical, in my opinion, rather than exegetical. What they come up with from the primary sources is the key—and I think that is what the courts have looked at, and that is why they have decided favorably on the side of what we have been doing for a long time.

Editor: Let me ask a question that goes to the core of this nation's commitment to religious accommodation: Do you believe that it would fit the law as well as the intention of the Founders if we were to have—at some distant point, given your tenure—a Muslim chaplain, a Buddhist, or some representative of a more elemental religion? Is that even feasible, or would that absolutely be against the intention of the Founders?

Black: I don't think that it would be against the intention at all. Although, I think that the demographics would need to change. When you are selecting a chaplain, you are selecting him or her to meet the spiritual needs of a certain constituency. If that constituency were significantly Islamic, then why not have an imam?

Editor: We regularly print articles in Liberty countering the developing idea of some religious leaders that this was overtly intended to be a Christian nation. That is sort of a loaded argument. Of course, those in the eighteenth century would have assumed theirs to be a Christian society; whether they intended this state to protect that cultural norm is a more problematic assumption.

Black: Well, that's where experience in inclusive ministry comes to bear. One of my best chaplains in the Navy was an imam. He grew up Baptist and converted to the Islamic faith. He had a sensitivity for Christianity. He knew the Bible better than most, and he facilitated the needs of his people better than my Christian chaplains. So the ability of a non-Christian to cross the lines of religious traditions would make him or her effective in a role such as this. And if the selection committee said that this is what we need, and the package that this individual brings meets our needs most effectively, then why not. However, I don't think in our lifetime that there is any likelihood of that happening.

Editor: Given the tenure of your position, that seems a reasonable position to take. But we are in a period of intense change and stress, much of it of a religious nature. I know that one of your Bible heroes is Daniel in the courts of Babylon. But I believe you are as significantly placed as Daniel ever was. May God bless you as you work to nurture spirituality in this place of power.

Article Author: Lincoln E. Steed

Lincoln E. Steed is the editor of Liberty magazine, a 200,000 circulation religious liberty journal which is distributed to political leaders, judiciary, lawyers and other thought leaders in North America. He is additionally the host of the weekly 3ABN television show "The Liberty Insider," and the radio program "Lifequest Liberty."