A Complex Relationship

Melissa Reid November/December 2004

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

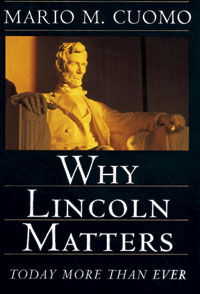

Cuomo introduces his readers to Lincoln as one who would help us overcome our lack of identity as a nation. "In recent years we have seemed unable to decide exactly what we want to be as a nation." "We yearn for a vision worthy of the world's greatest nation." Lincoln's philosophy of government was driven by his respect for individual dignity and the idea that all men are created equal. Implementation of the Declaration of Independence was the great goal to be achieved if America was to fulfill its promise as a democratic government. If we look to Lincoln, Cuomo tells us, we can find our reason for being. "Lincoln's belief in the American people and the inspiration we can provide the rest of the world was broader, deeper, and more daring than any other person's of his age—and perhaps, of ours, too." In Why Lincoln Matters we learn what Lincoln had to say about war, civil liberties, the role of government, opportunity, global interdependence, religion, the Supreme Court, and race. We shall limit our review to civil liberties and religion. Cuomo wishes that President Bush had not followed the example of Lincoln, who suspended the writ of habeas corpus (i.e., the right to challenge one's detention before a court or judge), who suppressed two newspapers, and who provided unappropriated funds to purchase military equipment. The U.S.A. Patriot Act is clearly in line with these suspensions of constitutional rights in the name of security. But Cuomo concedes that Lincoln "acknowledged that only in the kind of emergency he faced should a president ignore the Constitution as he did." Lincoln also promised to restore Constitution guarantees as soon as peace returned. The relationship of Lincoln to religion is more highly revered by Cuomo. Lincoln, although not a member of a formal church body, was an admirer of religion. We learn, for instance, that Lincoln visited Brooklyn twice during the 1860 campaign to listen to the sermons of Henry Ward Beecher. As president he attended Sunday services, preferring a church "whose clergyman holds himself aloof from politics." Cuomo tells us Lincoln would not support direct subsidies to religious groups. He would not favor posting the Ten Commandments on public buildings. And he would not insist that his party was based on the teachings of Jesus Christ. How would Cuomo define the religious principles of Lincoln? "We need to love one another, to come together to create a good society, and to use that mutuality discreetly in order to gain the benefits of a community without sacrificing the importance of individual freedom and responsibility." |

The timely dialogue initiated by Cuomo and Souder in 2002 has continued in the recent publication One Electorate Under God? A Dialogue on Religion and American Politics (edited in part by Brookings Institute senior fellow E. J. Dionne, Jr., one of the moderators of the Cuomo/Souder debate, which is included in the book) and in the July 21, 2004, Pew Forum's discussion of the same name between Congressman Souder (R-IN), Congressman David Price (D-NC), Dionne, Jr., and New York Times columnist David Brooks.

Reid: Can you briefly explain how a public servant can reconcile his or her personal religious convictions when serving a pluralistic constituency? Does the separation of church and state imply separation between religion and politics?

Cuomo: A religious commitment binds you personally to certain conduct and to refrain from certain other conduct. And so if you are a Roman Catholic, growing up as I did and have, and continue to, I hope, there are certain prohibitions that you must live by. You get married and stay in the marriage under certain circumstances. You cannot use birth control devices, and you cannot have an abortion, etc. And there is no difference in your religious obligation if you are in public life or not. If you are a public official or not, that personal responsibility remains your responsibility at all times.

No matter what the civic law is. And then as a politician you have another obligation, and that is to the civil law. Depending on what you are—a lawmaker, executive, or mayor—this takes different forms. But the obligation is to serve the public, and you take an oath to do that. And the oath says that you will live by the Constitution, and that is an oath that is allowed to Catholics and others by most religions. And so you swear to uphold the Constitution.

Now, there are not a whole lot of times when you are confronted with a question of "Well, I am now being asked to do something that my religion wouldn't permit me to do." For example, you are never ordered to commit an abortion or to accept an abortion. You are never ordered to practice birth control or not to, etc. You are never ordered to get married or to divorce. So there aren't many times when you are ordered to act personally against your conscience. So the question comes up, well, what is your obligation to take your religion and make it the religion of the whole society? To what extent are you obliged as a public servant, or even not as a public servant, to proselytize, to take the good rule that binds you within the Catholic Church and insist that all people, whether they are Catholic or not, live by it?

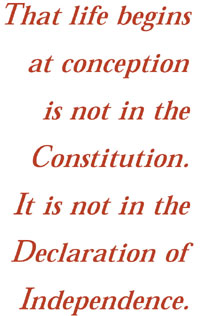

Now, some of the rules in the Christian religions are obviously rules that would appeal as much to our nonreligious, even religion-hating, people as they do to the religious people. For example, murder. You should not kill another human being. You are obliged to this [rule] as a Catholic, as a Christian, and in most religions because it violates the most obvious religious predicates. It also in almost all civil societies violates the civil law, and so there is no collision there. I'll use murder because that's the one that people use most often with respect to abortion. The difficulty with abortion is it starts with your religious beliefs, starts with the proposition that life begins at conception. That life begins at conception is not in the Constitution. It is not in the Declaration of Independence. It is not the statute of any state that I am aware of. It is not in the decisional law of the Supreme Court of the United States. It is basically a religious predicate for Catholics, and incidentally, it wasn't always a religious predicate for Catholics.

And so the question there becomes, What is a Catholic's obligation? Is it to devote every power you have as a voter, as a mayor, as a governor, as a member of Congress, as a president, to make everybody act on the assumption that life begins at conception? Is that your obligation? If that were true, then the church would have to explain why it is not pushing against birth control. And contraceptives. Why it didn't push against slavery in 1865 and why it did allow the bishop to have slaves. You have to go to John Courtney Murray, who made clear in the 1950s that the Catholic Church has a prudential rule that sometimes you push the point and sometimes you don't, depending on whether it works practically to your advantage. And so Catholics as a church formal did not fight slavery. Now, does that mean that they believed in it? Many years before the nineteenth century the pope had said slavery was wrong, but that didn't make the Catholics militant in the nineteenth century because they were so weak in this society that they didn't feel obliged to or even enabled to.

Another example is the law against contraceptives. I don't think that's in any way diminished recently, but I don't hear cardinals or bishops chasing people out of their church and away from the rail because they're involved in contraceptives. So I think it is a prudential question for you and your conscience. What is your role in respect to these things? If the position you take on the subject of abortion as a Catholic is that you believe that abortion is wrong and therefore we must have a constitutional amendment declaring that life begins at conception, and therefore abortion, even if it means the life of the mother, should be forbidden in the United States of America, that is the only Catholic position you could take. You would be obliged—starting with the president of the United States if he were a Catholic, every member of Congress, and every voter—to say that we must have a constitutional amendment. Have you heard the Catholic Church asking for it?

Reid: Recently politicians and judicial nominees on either side have been criticized for being either too Catholic or not Catholic enough. Where is the line between the appropriate probing of a public figure's political view and inappropriate and possibly unconstitutional religious tests for office?

Cuomo: I like what the Founding Fathers do in the Constitution as a practical matter. They don't talk about God; they talk about religion. In the United States of America our Supreme Court has declared that there are several recognized religions—like Confucianism, Buddhism, Hinduism—that have no God. So "religion" is different from a belief in God. The Founding Fathers don't talk about "God," and the Declaration of Independence doesn't talk about "God"; it talks about "nature's God." That is the natural law that you would have gotten at without anyone coming down a mountain with a beard and a stone tablet. So you have to be very careful about distinguishing between religion and God.

So they say "religion" is presumably a body of beliefs with affirmation and rules and prohibitions and prescriptions, but it is a whole body of belief. And they say that religions, because they are so important to individuals and so different one from another, can cause trouble. Why? By following your religion, you define yourself as different from me, because I have a different religion. And I have a religion that says polygamy is good, and you have a religion that says it's sinful. So we—having had all this experience in the places where we came from—are going to keep the religions separate; we are going to say that we established this country in part to give people religious freedom and liberty as much as possible.

So that is a principle that we are going to put right in the First Amendment. You are free to be a Catholic, a Baptist, a Calvinist, whatever else you want to be. It's absolutely clear that you have the right to be religious; however, we want to avoid a situation where you have a Muslim state or a Catholic state or a Protestant state or a Jewish state, because that will only inhibit your religious freedom. And so the government cannot establish a religion. We don't want the government being in the religion business. And that crude but very clear wisdom is the heart of the matter. You are free to be religious, but the government shouldn't get involved because they'll foul it up by getting involved. It inhibits freedom.

Those are the basic principles. Now the difficulty is in interpreting those basic principles, nailing them down to the procrustean bed of reality. At what point do you say you are establishing a religion? Is it when you say I can use my money that the state gave me to go to a seminary? Some people will say yes; some people will say no. They will both agree with the general propositions, but they will say, "Look, when you said establish, I didn't mean that. I meant having a pope sitting as president." So I am not embarrassed by all the questions that come up.

If you are a religious institution like Catholic Charities in New York, should you have to use your wealth to pay for birth control devices and the practice of birth control by the people who work for you? On the one hand, they will say, "No, we are now pushing something that our religion prohibits." And the other people would say, "No, your religion prohibits it to you; your workers may not be Catholic." And that is the quarrel.

Cuomo: I have this section on religion and a section on the suspension of civil liberties in my new book [Why Lincoln Matters: Today More than Ever]. Lincoln set a record: up until him nobody had done to the Constitution what he did to it in terms of suspending the writ of habeas corpus, locking people up, and tearing down newspapers, etc. I am not a Lincoln scholar; however, I have been a Lincoln student all of my adult years, virtually since the collected works by Roy Basler in 1955. So for half a century I've been reading and studying. I do know that he suspended habeas corpus, etc.—I think unnecessarily and therefore wrongfully. I think the Patriot Act is similarly excessive in some regards. And that is what I say in the book, in a chapter on the suspension of civil liberties.

Article Author: Melissa Reid

Melissa Reid is the associate editor of Liberty.