A Matter of Honor

Clifford R. Goldstein March/April 2020It was one of those “by invitation only” events. A special, select group alone could attend: military people, journalists, and a few notables. However, a large crowd of the unchosen gathered outside the walls, making its presence known with shouts of “Death to the Jew!” and “Death to Judas!” The mob numbered in the thousands, filling the Parisian streets outside the principal courtyard of the École Militaire, on Place Fontenoy, where on the morning of January 5, 1895, a “ceremony of degradation” was unfolding.

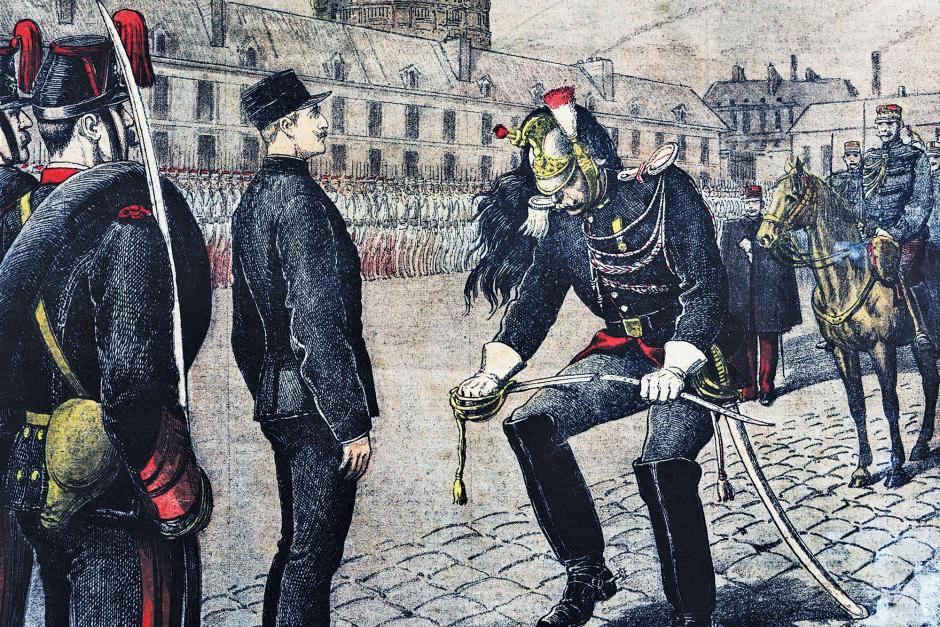

First a drum roll, and then General Paul Darras, on a horse in the center of the courtyard, drew his sword. A soldier walked out, escorted by a brigadier and four gunners. The escort brought the man before the general and withdrew, leaving only the soldier and the general, who glared down at him as a government official read aloud, for all to hear, the court-martial verdict. Then, still on the horse but rising in the stirrups, his sword held high, General Darras pronounced the words: “Alfred Dreyfus, you are no longer worthy of bearing arms. In the name of the people of France, we dishonor you.” Instantly, in what had been and would be the poor man’s mantra for years to come, Alfred Dreyfus shouted back: “Soldiers, an innocent man is being degraded; soldiers, an innocent man is being dishonored. Long live France! Long live the Army!”

Next, another soldier approached Dreyfus and began ripping the decorations off his cap and sleeves, the red stripes off his trousers, and the epaulets off his shoulders. Taunting Dreyfus, who stood erect, he grabbed Dreyfus’ sword and broke it over a knee. Again, Dreyfus declared his innocence: “Long live France! I am innocent! I swear it on the heads of my wife and my children!”

His clothes tattered, Dreyfus was forced to march before the line of troops assembled in the courtyard, who stared at him in an icy, hateful silence. Meanwhile, outside, the cries “Death to the Jew!” grew louder. As he passed before the “press box,” he shouted, “You must tell all of France that I am innocent.” Then (in an act that shows how journalistic standards have changed), some from the press responded with jeers and scorn, yelling back at him: “Coward! Judas! Dirty Jew!”

The “ceremony of degradation” over, Dreyfus was unceremoniously hoisted onto a prison car, for a trip to a jail in Paris, a holding cell for what his prison term for treason was to be: life imprisonment on Devil’s Island, a little piece of hell off the coast of French Guyana.

L’affair Dreyfus

On one level, however sad this event, it shouldn’t have been that big a deal. A soldier court-martialed. Probably happens in most militaries, if not all the time, then still enough not to warrant the worldwide attention this court-martial did.

Indeed, this whole story, and even this particular scene (the “ceremony of degradation”) has been the subject of books, movies, magazine and newspaper articles, documentaries, theater, and radio for more than 100 years, and in numerous languages, too. For decades afterward France was greatly divided over the fate of this poor man. It was the Dreyfusards against the anti-Dreyfusards, and the split occurred even within families. Today the story remains well-known in France, with books and articles about L’affair Dreyfus still coming off the press.

And that’s because the story is worth remembering, not just in France but anywhere people care about justice. And though the foul taint of anti-Semitism was, clearly, behind everything in this case, the issue could be seen as something even bigger: how, in times of crisis or in heated racial and ethnic and political tensions, it’s easy to find scapegoats, to find “the other” to blame for our problems, regardless of how innocent the other happens to be.

What was the Dreyfus affair, what can we take from it today?

Background

It’s hard to talk about anything in France, especially in the century following the French Revolution, without some reference to 1798. After the revolution, which broke the back not only of the monarchy but of the Roman church, other groups, such as Protestants and Jews, began to flourish, especially economically. Resentment arose that, of course, helped feed what has always been a deep-seated problem in France anyway, and that was anti-Semitism. Meanwhile, military setbacks, especially against France’s longtime nemesis, Germany, as well as a series of political crises, fueled a right-wing nationalism that helped pave the way for poor Alfred Dreyfus, an artillery captain, to be cast into the annals of world history.

Dreyfus, a ”secular” Jew from a relatively well-off family, worked his way through the ranks of the military, which he loved, eventually serving a term with the General Staff of the Army, in 1893. Happily married and the father of two very young children, Captain Alfred Dreyfus had written about this time: “A brilliant and easy career was open to me; my future seemed most auspicious. After a day’s work, I returned to the tranquility and charm of family life. . . . Our happiness was complete. . . . I had no financial worries; the same deep affection bound me to the members of my family and to those of my wife’s family. Everything in life seemed to smile at me.”

The smile, however, would quickly turn into a sneer.

The Bordereau

Despite more than a century of dissection from so many angles, some points, especially motives, remain unknown. But what is certain is that Alfred Dreyfus was arrested and convicted of treason—a crime that he had definitely not committed.

The narrative went, essentially, like this. In 1894 a housekeeper working for French Military Intelligence Service, while stationed at the German embassy in Paris, supposedly found, in a wastebasket, a document, to be known as the “bordereau.” However French Intelligence really did get hold of it (most historians today discount the wastebasket story), the document, partially torn into six large pieces of tissue paper, was addressed to the German attaché stationed at the embassy, Max von Schwartzkoppen. It had information regarding confidential military documents about French troop movements and military equipment.“From its first sentence,” wrote Jean Denis Bredin, in a recent book about Dreyfus, “the letter indicated the existence of a treasonous transaction. The traitor was apparently an officer, and undoubtedly (since the document alluded to the ministry) an officer of the Ministry of War. The information he disposed of seemed to be important. A French officer, probably of the General Staff, was thus implicated.”

The Arrest

The officer, not only implicated but arrested, was Captain Albert Dreyfus, who had two specific things working against him. First, he was from the Alsace, a region of France lost to the Germans in 1871, in the Franco-Prussian War. His Alsatian origins made him suspect because of the region’s close ties to Germany, even if the Alsatian ability to speak German (which Dreyfus had) made them valuable to the military. The second, and the bigger one, was that he was a Jewish officer in an exceedingly anti-Semitic army and at a time when anti-Semitic fervor was raging in France.

These two factors—added to the stark fact that other breaches of security made the need to find the culprit as much a political necessity as a military one—set up Dreyfus as the prefect scapegoat. He was, after all, the only Jew on the General Staff, and an Alsatian to boot.Thus, Captain Alfred Dreyfus was arrested in 1894, despite no evidence other than supposed handwriting experts who argued that his writing could have matched that found on “the bordereau.”

From the start he maintained his innocence, and after a few days in jail an officer put a revolver on a table in front of Dreyfus, suggesting he kill himself. Dreyfus refused, saying he needed to stay alive to prove his innocence.

The Trial, Conviction, and Imprisonment

Once the story of his arrest was made public, Dreyfus was crucified in the press. The anti-Semites had a field day. Among the sentiments expressed were: “He came into the Army with the intention of betrayal.” “As a Jew and a German, he detests the French. . . . A German by taste and upbringing, a Jew by race, he did the job of a Jew and a German—and nothing else.” “In every nasty affair, there are always Jews. Nothing could be easier than to organize a good cleanup.” “One day a Jew steals secret documents; the next day the same Jew grimaces as he sells papers to a German. The homeland is to be found wherever the money is good.”

The three-day farce of a trial in December of 1894, which was closed to the public, returned an unanimously guilty verdict by a seven-judge court, and by April 1895 Albert Dreyfus was imprisoned on Devil’s Island, off the coast of South America, where he was sentenced for life.

Though now supposedly over, L’affair Dreyfus had only just begun.

The Rise of the Dreyfusards

Though most of France was convinced of Alfred Dreyfus’ guilt, he had defenders, including his elder brother, Mathieu, who, despite threats of arrest, and at great personal expense, worked tirelessly on behalf of his brother. Mathieu did find sympathizers on the left, but they had little influence.

A break came with the appointment, in 1896, of Georges Picquart as the new head of the army’s intelligence unit, who reexamined the court-martial. Surprised at how thin the case against Dreyfus was, he came across a document, written in the same handwriting of “the bordereau” but belonging to another army officer, Major Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy—now universally regarded as the guilty party.Picquart’s superiors, however, discouraged him from his inquiry; his refusal to back down got him shipped off to North Africa and, eventually, imprisoned.

Word, however, about Esterhazy became public, and pressure mounted on the military. In 1898 Esterhazy was court-martialed but, in a sham of a trial, he was acquitted. In response to the obvious farce, a French newspaper published an open letter, titled “J’Accuse…!” (“I accuse!”) by well-known author Émile Zola, who not only presented a powerful case for Dreyfus’ innocence but named those in the military and the government he accused of complicity in the coverup. The article created an international furor (the daily circulation of the paper was 30,000; the edition with “J’Accuse” sold about 300,000). Zola, for his efforts, was convicted of libel and escaped to England, but he did get what he wanted, and that was a new trial for Dreyfus.

The Return of Alfred Dreyfus

Thousands of miles away, Albert Dreyfus had no inkling of what was happening. Then, in June of 1899, he was notified about the decision for a new trial. After five years on Devil’s Island, he was back in France, now in a military prison in Rennes. Amid incredible tension, another sham of a trial unfolded, and even though Esterhazy had confessed to writing “the bordereau,” the military, having gone this far, wasn’t about to back down. Dreyfus was again found guilty, though this time “with extenuating circumstances,” and was sentenced to 10 years’ imprisonment.

Amid the raging controversy, and with a desire to end the affair, which brought France almost universal condemnation, Dreyfus was offered a pardon. Exhausted, beaten down, and away from his family for years, he reluctantly accepted. On September 21, 1899, Albert Dreyfus was, finally, a free man, but the taint, the stain, remained.

In July 1906 a civilian court of appeals revoked the verdict at Rennes, and restored Dreyfus to his rank as captain, but with seniority of 17 years. It also conferred on him the rank of squadron chief, as well as awarding him the Cross of the Legion of Honor. In other words, seeking to undo the injustice done, they gave not only a promotion but a medal as well—the highest that France had to offer.

Indeed, in the same École Militaire where, 12 years earlier, he endured the “ceremony of degradation,” another ceremony now took place. Before an assembly of troops and dignitaries, General Henry Gillain, face-to-face with Dreyfus, announced to him and the assembly: “In the name of the president of the Republic, and by virtue of the powers invested in me, I hereby name you Knight of the Legion of Honor.” His sword descended three times on Dreyfus’ shoulder. General Gillain next pinned the cross on Dreyfus and then embraced him. At the sound of a brass band, the general and Dreyfus marched before the troops. Some embraced Commandant Dreyfus, some shook his hand, and some shouted, “Long live Dreyfus!”

“No, gentlemen,” he shouted back. “I beg you. Long live the Republic!”

Dreyfus then served for another year in the military, retiring in 1907 because of bad health, exacerbated by five years on Devil’s Island.However, as a reservist, he was called up in World War I and fought on the front lines at Verdun. He died in 1935.

The French army, however, didn’t fully exonerate Dreyfus until 1995.

So What?

Besides the obvious and still consequential issue of anti-Semitism, the question remains: What does this sad story mean for us today? No doubt, L’affair Dreyfus shows, if nothing else, that even just societies can perpetrate gross injustice, especially when the victims of that injustice are from an outside class. Though some have tried to equate the fate of poor Alfred Dreyfus with that of prisoners at Guantanamo Bay, it’s quite a stretch to find much of a parallel between an innocent officer framed for treason and inmates at Gitmo deemed too dangerous a terror risk to release. Nevertheless, especially in a time of fear, it’s easy for any nation, even one like France—which prided itself on its protection of human rights—to violate those rights.

Others have seen in this story a powerful expression of the role that the press, and public opinion, must play in a democracy. Whatever one might think of American journalism today, it was the press, and the public intellectuals who rallied with it, that saved Dreyfus from rotting to death in disgrace on Devil’s Island.

And in an era of whistleblowers and sworn testimony; of partisan demonizations and regular impugning of loyalty, it is worth remembering the stakes when truth is subverted so systematically.

Despite more than a century of dissection, interpretation, revision, and pontificating, perhaps the message from this unfortunate incident is simple. All free nations have an Alfred Dreyfus (or more) among them. The challenge is not to succumb to whatever circumstances, especially in troublous times, that could turn a simple artillery captain into their own L’affair Dreyfus, especially one that might not have such a “happy” ending.

Clifford Goldstein writes from Mount Airy, Maryland.

Article Author: Clifford R. Goldstein

Clifford Goldstein writes from Ooltewah, Tennessee. A previous editor of Liberty, he now edits Bible study lessons for the Seventh-day Adventist Church.