America Comes to Rome

Joseph K. Grieboski September/October 2008

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

When the Vatican announced last fall through Archbishop Pietro Sambi, papal nuncio to the United States, that Pope Benedict XVI would be visiting the United States, "professional Catholics," pundits, clerics, and even politicians debated the meaning and message of his first papal "voyage" to the United States. In fact, it had been nearly 10 years since his predecessor, Pope John Paul II, had visited the United States.

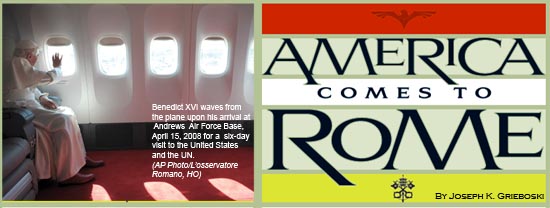

Most Americans had perceptions and thoughts about Pope Benedict before his April 15, 2008, arrival in the United States. The average American expected to see a conservative, dour, and authoritarian man, an image built from his many years defending orthodox Catholicism as prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. Even the "in crowd" of Catholic educators, theologians, hierarchs, and policy wonks expected America to receive a papal thrashing for losing its way and heading toward hedonism.

Instead, America met a gentle, loving, compassionate man of thought; a prayerful leader whose insights and thoughtfulness and message of prayerful coexistence far made up for the charismatic affability and dramatic presence of his predecessor. But very much like his predecessor, Benedict made fundamental rights, especially religious freedom, a centerpiece of his message to the United States

As Rocco Palmo—who writes from America for The Tablet, the international Catholic weekly published in London—stated after the papal visit, "Lest anyone still be looking for a program, a roadmap for the future of the American Catholic project, it's in our midst. We've got it. And soon—now—the prayer and work begins to make it a reality."

With "Christ Our Hope" as the theme of his visit, Pope Benedict XVI brought a burst of energy, optimism, and faith to American Catholicism—and to America itself—during his five-day visit, and with it a new air of responsibility for both. "I have had the joy of personally visiting, for the first time as the successor of Peter, the dear people of the United States of America, to confirm the Catholics in their faith, to renew and increase fraternity with all Christians, and to announce to everyone the message of 'Christ Our Hope,' as the theme of the trip said," the pope commented after his return to Rome.

Let us not assume, however, that Pope Benedict's visit was simply an opportunity for him to show his affection for the United States, its history, and its people. The pope, by virtue of his office, is a teacher. And as the theme of the trip suggested, Pope Benedict taught with clarity, vision, and principle the hope that is in Christ—in our daily lives, in our prayer lives, and in our public policy, especially in defense of fundamental rights.

Pope Benedict addressed some of America's more crucial issues during his visit, even addressing a hot political topic during his first public meeting: "Brother bishops, I want to encourage you and your communities to continue to welcome the immigrants who join your ranks today, to share their joys and hopes, to support them in their sorrows and trials, and to help them flourish in their new home."

Three paragraphs into his address, Pope Benedict reminded the hierarchs that "this, indeed, is what your fellow countrymen have done for generations. From the beginning, they have opened their doors to the tired, the poor, the 'huddled masses yearning to breathe free' (cf. sonnet inscribed on the Statue of Liberty). These are the people whom America has made her own."

At a time when America as a whole is divided over the politics, security, economics, and finance of immigration, Pope Benedict reminded the American bishops—as the successors to the apostles—that immigration is not an issue; it is a people—it is a young girl escaping murder in Honduras; it is a family seek-ing medical attention in the United States; it is a young man trying to find work to support his extended family at home. Benedict reminded the bishops—and all Americans—that immigration is more than an issue; it is a face.

Benedict did not sugarcoat his message to the people of the United States. The pope remained strong in his upholding of fundamental Christian truths in the context of American politics, history, and liberty.

Throughout his visit, the pope high-lighted the importance of fundamental values and liberties, emphasized within the American context. At the welcoming ceremony at the South Lawn of the White House, he said: "Historically, not only Catholics, but all believers have found here the freedom to worship God in accordance with the dictates of their conscience, while at the same time being accepted as part of a commonwealth in which each individual and group can make its voice heard. . . . Freedom is not only a gift, but also a summons to personal responsibility. Americans know this from experience—almost every town in this country has its monuments honoring those who sacrificed their lives in defense of freedom, both at home and abroad. The preservation of freedom calls for the cultivation of virtue, self-discipline, sacrifice for the common good, and a sense of responsibility towards the less fortunate. It also demands the courage to engage in civic life and to bring one's deepest beliefs and values to reasoned public debate. In a word, freedom is ever new."

During his meeting with President George W. Bush, the pope paid "homage to this great country, which from the beginning has been constructed based on a pleasing joining together of religious, ethical, and political principles, and continues to be a valid example of healthy secularism, where the religious dimension, in the diversity of its expressions, is not only tolerated but valued as the 'soul' of the nation and the fundamental guarantee of the rights and duties of the human being."

And later to the bishops he reiterated that "respect for freedom of religion is deeply ingrained in the American consciousness—a fact which has contributed to this country's attraction for generations of immigrants, seeking a home where they can worship freely in accordance with their beliefs."

Benedict carried his message of fundamental rights, especially that of religious freedom, throughout his many visits. During his address to the United Nations General Assembly, the pope emphasized that "human rights, of course, must include the right to religious freedom, understood as the expression of a dimension that is at once individual and communitarian—a vision that brings out the unity of the person while clearly distinguishing between the dimension of the citizen and that of the believer. The activity of the United Nations in recent years has ensured that public debate gives space to viewpoints inspired by a religious vision in all its dimensions, including ritual, worship, education, dissemination of information and the freedom to profess and choose religion. It is inconceivable, then, that believers should have to sup-press a part of themselves—their faith—in order to be active citizens. . . . The full guarantee of religious liberty cannot be limited to the free exercise of worship, but has to give due consideration to the public dimension of religion, and hence to the possibility of believers playing their part in building the social order."

Acclaimed Catholic writer and commentator George Weigel stressed that "the pope's U.N. address . . . made an intriguing argument: human rights, which can be known by reason, are the moral 'language' by which the world can turn dissonance into conversation."

The pope's comments on religious freedom made during his visit to the United States tend to go further than even those of his predecessor, who can well be known as the Pope of Freedom. During his meeting with representatives of other religions in the "Rotunda" Hall of the Pope John Paul II Cultural Center in Washington, D.C., Benedict stated that "the task of upholding religious freedom is never completed. New situations and challenges invite citizens and leaders to reflect on how their decisions respect this basic human right. Protecting religious freedom within the rule of law does not guarantee that peoples—particularly minorities—will be spared from unjust forms of discrimination and prejudice. This requires constant effort on the part of all members of society to ensure that citizens are afforded the opportunity to worship peaceably and to pass on their religious heritage to their children."

Benedict is not stepping back in his defense of religious freedom, even going so far as to mention minorities specifically in his statement. And actions do speak louder than words, as religious minorities were invited to meet with the pope.

Religious liberty continued to be a centrality of the pope's message, but in a different guise: spiritual independence. As the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life's U.S. Religious Landscape Survey states, "A major survey by the Pew Research Center's Forum on Religion & Public Life finds that most Americans have a nondogmatic approach to faith. A majority of those who are affiliated with a religion, for instance, do not believe their religion is the only way to salvation. And almost the same number believes that there is more than one true way to interpret the teachings of their religion."

Maintaining that self-defined spiritual values and practices without communal aspects is in violation of the earliest biblical teachings, Benedict called on American Catholics to remain steadfast in the church's communal identity: "In a society which values personal freedom and autonomy, it is easy to lose sight of our dependence on others as well as the responsibilities that we bear towards them. This emphasis on individualism has even affected the church (cf. Spe Salvi, 13-15) giving rise to a form of piety which sometimes emphasizes our private relationship with God at the expense of our calling to be members of a redeemed com-munity. Yet from the beginning, God saw that 'it is not good for man to be alone' (see Gen. 2:18). We were created as social beings who find fulfillment only in love—for God and for our neighbor. If we are truly to gaze upon Him who is the source of our joy, we need to do so as members of the people of God (cf. Spe Salvi, 14). If this seems countercultural, that is simply further evidence of the urgent need for a renewed evangelization of culture." A new religious liberty issue will begin to develop in America as more and more people identify themselves as spiritual but don't claim membership in or allegiance to a particular religious community. In his address to Catholic educators, Benedict highlighted the need to remain steadfast in faith when developing the understanding of freedom: "While we have sought diligently to engage the intellect of our young, perhaps we have neglected the will. Subsequently we observe, with distress, the notion of freedom being distorted. Freedom is not an opting out. It is an opting in—a participation in Being itself. Hence authentic freedom can never be attained by turning away from God. Such a choice would ultimately disregard the very truth we need in order to understand ourselves."

Pope Benedict XVI "shocked" ostensibly Protestant America with his com-passion, openness, and warmth during his visit, fundamentally shifting the perception of most Americans about the successor to Pope John Paul II (and Saint Peter). But more than his vision was his message of coexistence, cooperation, and promotion of fundamental rights and his demonstrated commitment to them that awed and impressed the American people. Pope Benedict has a new friend in the people of the United States.

Joseph K. Grieboski, a loyal son of the Roman Catholic Church, is founder and president of the institute on religion and Public Policy, based in Washington, D.C. He last wrote on the pope in our march/April 2007 issue with an analysis of the Regensburg speech. Then, as here, his observations were well placed and accurate. Then, as here, Liberty editor Lincoln steed elaborated on the larger significance for Protestants and for Protestant America. See the editorial on pages 2 and 3 of this issue for the editorial perspective.