Anguish and Anger

Reuel S. Amdur May/June 2011

The turmoil in Egypt has led to the spilling of considerable quantities of ink and blood since it all started on January 25. The regime of Hosni Mubarak is already a footnote on the pages of history, but the near and longer-term future remains to be spelled out. One concern is what it all means for Egypt's long-suffering Coptic minority, which has frequently been the victim of violence. Periods of instability can give more opportunities for fanatics to act out.

There are various estimates of the Christian portion of the Egyptian population, but it is generally believed to be between 10 and 20 percent—most being Orthodox Copts, an ancient denomination predating Islam. Tradition ascribes its founding to the apostle Mark. This branch of Christianity separated from Rome following the Council of Chalcedon, over the issue of Mary. Rome called her the mother of God—Copts called her the mother of Jesus. For Catholics the result was development of the doctrine of Mary's Immaculate Conception. Over the years Copts have been victims of violence and of official discrimination. On New Year's Day a suicide bomber blew up his explosives-laden car in front of a Coptic church in Alexandria, Egypt, killing 25 and wounding dozens. Because of the extent of the planning and technical expertise, it was suggested there was an al-Qaida link—certainly radical Islam. While Copts have been victims of many other attacks, these have typically been more amateurish in nature, although the violence has been real enough.

Less than two weeks after the Alexandria massacre a policeman boarded a train in Samalout, bound for Cairo, and fired his weapon at Copts, killing one and wounding five, while shouting, "Allahu Akbar [God is great]."

Coptic Orthodox Christians demonstrating against the bomb attack in front of the Coptic Orthodox Church in Alexandria January 2, 2011, carry an image of Jesus that had been located near the side gate to the church compound, and was splattered with blood during the attack.

Yet in spite of all the difficulties faced by Copts in Egypt, some have risen to prominent positions in government and in business and the professions. Nor are relations between Muslims and Copts entirely negative: after the New Year's Day bombing, many Muslims were prepared to stand guard at the Alexandria church during their Christmas service this year, and when the police would not allow them to do so, large numbers of Muslims attended the Mass. (December 25 on the Coptic and Julian calendars occurs on our January 7.) Many Muslims and Copts are friends and associates and often live together in the same neighborhoods. Yet the incidents are not infrequent.

Almost a year before the killings in Alexandria, on January 7, 2010, six Copts leaving church after Christmas Mass were cut down in a hail of bullets in a drive-by shooting. A Muslim guard was also killed. After the Christmas massacre, there was more trouble for the Copts. Immediately following, many local teens were arrested in dawn raids, apparently to prevent protests. There was some rioting by Christians, possibly at least in part as a result of the arrests. Two women were burned to death in a nearby town, where houses were set ablaze and businesses looted and destroyed. The next month, a policeman shot and killed a man in Teta, in an incident that the government claimed was because of an accident during the cleaning of the weapon. A relative who witnessed the incident denied the official version.

Over the years Copts have suffered a number of pogroms and less-extensive killings, as well as assaults on houses and property and on their churches and monasteries. In 1999 Copts in el-Kosheh felt the wrath of their neighbors in three days of slaughter and destruction. In that case, 21 were killed, 33 injured, and 260 houses and businesses destroyed. More than 1,000 Copts were arrested and brutalized to make them take the blame for the pogrom. Copt witnesses were able to identify a number of the assailants, but only three were convicted—not for murder but for possession of illegal weapons and destroying a truck.

In March 2010 Marsa Matruh was the scene of a Muslim rampage, during which a community center was attacked and houses, cars, and other property were destroyed. This incident was said to have followed an incendiary sermon by an imam.

In 1981, because Copts were even then fed up with government failure to protect them from violent attacks, the Coptic pope Shenouda III canceled public Easter ceremonies. Traditionally, government representatives attend these ceremonies. In response to this snub, Anwar Sadat, who was then president, banished Shenouda to a remote desert monastery. Mubarak released him, as a result gaining gratitude from Shenouda and from the Coptic community.

In looking at the causes of these various incidents we can sometimes identify specific triggers, but there are also some larger general factors. Let us first start with some specifics. In the case of the Alexandria slaughter, the story is that two wives of Coptic priests, desirous of obtaining a divorce, which is forbidden to them under Coptic Church regulations, attempted to convert to Islam for that purpose. It is alleged that Copts prevented them from doing so. The attack on the Nagaa Hammadi parishioners was related to an accusation that a Copt had raped a young Muslim girl. Other incidents involved property disputes, individual conflicts, and personal relationship issues—for example, young Copt males involved with Muslim girls. And, as in a previously mentioned incident, there has been incitement by some imams.

While the Nagaa Hammadi killings can be seen as a primitive kind of revenge in a country in which the legal system has been, as Samaa Elibyari of the Canadian Council of Muslim Women described it, "corrupt and inefficient," the main factor is the vulnerability of minorities. Ehab Lotayef, a Muslim active in Canadian Egyptians for Democracy, said that other religious minorities also face discrimination, including non-Orthodox Coptic Christians, Baha'is, and even Shiite Muslims. Egyptians carry identity cards indicating religion, and only recently did a court rule that Baha'is had the right to that designation on theirs.

Even Sunni Muslims whose beliefs are not in accord with orthodoxy can be targeted. A notorious example is the case of Nasr Abu Zayd, a distinguished scholar of Islam, whose works were deemed by some people in positions of power to be heretical. As an apostate under Sharia law a Muslim woman may not be married to a non-Muslim, his wife was ordered by the court to divorce him. They fled the country.

Both Copts and Muslims interviewed identified the growing influence of Wahhabism, the austere and primitive form of Sunni Islam dominant in Saudi Arabia, as an important factor in the anti-Copt violence. Saudis have funded Muslim religious institutions and programs around much of the world to promote this brand of Sunna. Some Egyptians who worked in the Gulf States brought this strain of Islam back with them.

The Muslim Brotherhood, which is somewhat influenced by Wahhabism, is an important element in Copt insecurity, though they have spoken out clearly against the massacres in Alexandria and Nagaa Hammadi, as well as the al-Qaida slaughter of Christians in a church in Iraq. Even while outlawed, the Brotherhood formed the main opposition to the government of President Hosni Mubarak. In Parliament its members are formally listed as independents. The Brotherhood has considerable popularity because it provides a variety of social services. By contrast, under Mubarak "the government didn't providing anything for its citizens," as Elibyari observed. The Muslim Brotherhood is not totally unified in outlook, ranging from somewhat moderate to more rigid. One leader of the movement has proposed a special tax on all non-Muslims. Nabil Malek, a Copt who heads the Canadian Egyptian Organization for Human Rights, encapsulated the classical Muslim position on non-Muslims in this way: "Non-Muslims have rights but not equal rights." That observation applies to the attitude of the Egyptian government under Mubarak, and the future government's policies remain to be seen.

What would life be like for Copts should the Brotherhood come to power in Egypt? In Gaza, under the Brotherhood-oriented Hamas, liquor sales have been closed down by threats of Islamists. The Hamas rulers have not officially banned Western-style attire for women, but they have not prevented head covering being imposed by local authorities or activists. A Christian bookshop was attacked by extremists, and there has been some harassment of Christians, though not sanctioned. Hamas itself has been challenged by more extremist Islamist elements. One should not be surprised if similar kinds of things happen in an Egypt under Brotherhood control.

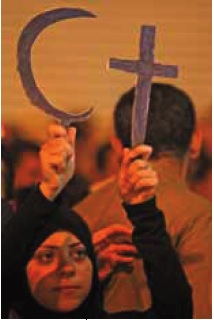

An Egyptian Muslim holds crescent and cross symbols in the Shobra district of Cairo January 1, 2011, to protest against a bomb attack on a Coptic Christian church in Alexandria.

All of this must be seen in the context of the Mubarak government. It was authoritarian but not totalitarian. Mubarak maintained control by a balancing act, placating different factions in his own government and in the country as whole and maintaining relations internationally. Egypt gets significant military aid from the United States, for example. As far as the Copts are concerned, Mubarak received their support but returned only partial protection in order not to upset those Muslim elements that are virulently anti-Christian.

Copts in Egypt are in a difficult situation. They have a well-founded fear of Islamic extremists, and they have gotten at best desultory protection from the Mubarak government. The Alexandria slaughter could well be the incident that forces the new government's hand on that score. In the past, the concern was that if they complained too loudly they risked losing even that protection. If they said nothing, nothing would be done for them. They tended to give support to the dictatorship in hopes that their support would pay off. As well, they remembered the fact that Mubarak released their pope from imprisonment in the monastery.

As Hosni Mubarak is being pushed out, Pope Shenouda continues to give him full support. On January 31 he called Mubarak and told him, "We are all with you, and the people are with you." However, according to the newspaper Al-Masry Al-Youm, the Coptic Youth Movement has joined the opposition. "The regime is responsible for the sectarian problems suffered by Copts," charged Rami Kamel, speaking for the movement. As well, media accounts reported that during one demonstration Christian participants stood guard while their Muslim comrades prayed. One slogan used in the demonstrations was "Cross and Crescent Together!"

During the dictatorship international pressures provided the one largely uninhibited form of influence on government policy toward the Copts. For that reason, the sizable Coptic diaspora has played a vital role. We can expect that the diaspora will continue to speak out should events demand. Their enemies complain that they encourage foreign interference in matters that should stay in Egypt, but this criticism is evidence that the international publicity is having an impact. Copts around the world have demonstrated in protest against the Alexandria massacre, and political and religious figures across the spectrum condemned the atrocity, including U.S. President Obama, Prime Minister Stephen Harper of Canada, President Nicolas Sarkozy of France, Sunni and Shiite clerics in Lebanon, and Palestinian National Authority President Mahmoud Abbas.

After the Christmas bombing, Copts also raised voices in protest around the world. Thousands rallied before the United Nations in New York on January 19, 2010, and two days later before the White House. Other protests occurred in Berlin and Vienna. Up to 8,000 rallied in Sydney, Australia, and others demonstrated in Melbourne, Australia.

The cries of anguish and anger by Copts were heard by governments. A group of congressmen and a senator called upon Egypt to ensure "equal protection of the law and equal rights for all citizens" and complained of "a systemic pattern of violence against Egypt's Coptic Christian population." Italian foreign minister Franco Frattini promised to raise the issue with his counterpart during a visit to Cairo. Pierre Poilievre, parliamentary secretary to the Canadian prime minister, spoke in support of Coptic rights at a commemorative service in which Egyptian embassy officials were present.

Toward the end of the Mubarak era there were some positive developments. Copts were granted a few favorable decisions on church repairs. The law requires local government approval before a church can carry out repairs, but one court gave permission without such approval, and in Alexandria, where police arrested a priest for doing repairs without authorization, the court found him not guilty. Most significantly, one of the men accused of the killing in Nagaa Hammadi was found guilty on January 16 this year and sentenced to death. Let us leave aside the issue of capital punishment: this decision appears to be a first in which attacks on Copts have been treated with such severity. Previously, incidents of anti-Copt violence have been ignored, given limited punishments, or blamed on the Copts themselves. The Alexandria bombing appears to have sealed the fate of the Nagaa Hammadi criminals.

A leading columnist, Makram Mohammed Ahmed, said, "I call upon the government to eliminate the reasons for sectarian tension, or we can have a bombing like this one [in Alexandria] every day." So what kinds of changes are needed? In a basic sense, Egypt needs to move toward being a country for all its citizens on an equal basis. It needs to allow churches to be repaired and constructed under the same rules as mosques are. It should not require special permission to fix a leak in a roof. There is no reason to include religion on identity cards. Sharia should not be the law, and heretical views should not subject the holder of such views to special government attention. If a woman wants a divorce, she should not have to change her religion to get one. It should be no more a Muslim country than the United States is a Christian one. What is needed is a separation of mosque and state. All of this is not quite enough. The police and correctional officials also need to be placed under firm control. Arbitrary arrests must be stopped, and torture by police and in prisons must be halted. These changes would be a good start, but will they occur? As with everything about Egypt, time will tell.

Article Author: Reuel S. Amdur

Reuel Amdur writes from Val-des-Monts, Quebec, Canada.