Assessing the Secular Threat

Kevin D. Paulson September/October 2013Advocates of religious freedom, be they genuine or merely self-designated, are astir in America just now. And many are deeply worried. They perceive a secular tide in the land, threatening to stifle the voice and visible practice of faith, at least the conservative kind.

When he was president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, Cardinal Francis George referred to what he called “threats to religious freedom in America that are new to our history and to our tradition.”1 Legal commentator Hugh Hewitt described one of these threats as follows:

“For three decades people of faith have watched a systematic and very effective effort waged in the courts and the media to drive them from the public square and to delegitimize their participation in politics as somehow threatening.”2

In a recent address to the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty annual dinner, accepting the organization’s Canterbury Medal on account of his defense of religious freedom, Mormon elder Dallin H. Oaks observed:

“Powerful secular interests are challenging the way religious beliefs and the practices of faith-based organizations stand in the way of their secular aims. We are alarmed at the many—and increasing—circumstances in which actions based on the free exercise of religion are sought to be swept aside or subordinated to the asserted ‘civil rights’ of officially favored classes.”3

Oaks continued by citing a cluster of statistics allegedly proving a growing secular trend in the United States, particularly among young adults. Among the figures quoted was a 19 percent total of Americans supposedly claiming no religious affiliation,4 a figure purportedly including 33 percent of young people.5 The 19 percent figure was cited as solidly ahead of mainline Protestants and exceeded only by evangelical Protestants and Roman Catholics, who hold the allegiance of 30 and 24 percent of the American public, respectively.6 Equally significant, according to these sources, is the claim that at least half the 19 percent noted in this context presumably possess “a genuine antipathy toward organized religion.”7

A Closer Look

Attaching meaning to these statistics may not, however, be as easy as some presume. What is not often understood, for example, is that many evangelicals who attend church regularly and hold devoutly to conservative Christian beliefs, consider themselves “unaffiliated” with any particular denomination. Many of these attend independent congregations that claim no ties to any larger institutional or hierarchical structure. Many such persons, despite their strong faith in Scripture and orthodox Christianity, might well classify themselves as hostile to what they perceive to be “organized religion”—meaning in their thinking such major denominations as Baptists, Lutherans, Methodists, Roman Catholics, etc.

Moreover, defining the word “secular” can be equally elusive when applied to a person’s worldview. Does this definition signify overt disbelief in the fundamentals of religion? Or does it simply mean no firm commitment to any particular set of beliefs? The old adage about “no atheists in foxholes” makes the thoughtful analyst hesitant to characterize too quickly even the most vehement of anti-religionists. I recall an interview given by former President Jimmy Carter, as he recounted a negotiating session between himself and then-Soviet Premier Leonid Brezhnev. In the course of one particular conversation, Carter recalled Brezhnev insisting loudly that “God will never forgive us if we don’t win!”—“we” referring apparently to the former Soviet Union. Carter noted in the interview how strange he considered that comment, coming as it did from the leader of an officially atheistic society.

Religious faith is as deeply ingrained in the human psyche as any expression of the human spirit. Perhaps this is why Scripture spends so little time addressing the challenge of overt atheism, other than to call one who denies God’s existence a fool (Psalm 14:1; 53:1).

Religious Freedom Is a Two-Way Street

But whatever its true strength may be, the secular challenge deserves to be taken seriously by advocates of religious liberty. The question is What do we do about it?

I truly believe no workable solution exists except for all parties concerned—devout biblical religionists such as myself, along with persons of a nonreligious mind-set—to acknowledge that religious freedom is a two-way street. Both camps must recognize and protect the rights of the other. The notion of certain ones that “we have to take their rights away before they take ours away” can only deepen the divisions and hostility that define so many of today’s cultural and political differences, particularly in the United States. A better solution must be found.

As a committed religious conservative myself, it pains me to admit that people who think like me have contributed to the current divisiveness in America over cultural and social issues. For more than three decades now, religious conservatism has become associated in many minds less with the proclamation of biblical teachings and the practice of biblical moral standards than with the use of civil force as a means of applying these teachings and standards to society. The notion that America is a “Christian republic” from which lifestyles and literature unbecoming to Christian principles must be legally purged, has evoked a negative response far stronger than would likely be aroused simply by the voluntary teaching, publishing, and reception of Christian values. The specter of coercion attached to these values by the political agenda of the Religious Right has grown particularly offensive at a time when the religious zeal of certain ones—Christian and otherwise—has exploded into occasional violence. Anti-religionists in our day point repeatedly to such incidents as proof of the essentially toxic nature of religious faith—not apparently considering that overtly godless “reason” has a no-less-brutal track record in the human story.

Dallin Oaks’ reference to what he calls the “civil rights” of “officially favored classes,” more than likely a reference to practicing homosexuals and their current quest for marital and employment rights, bespeaks a mind-set that is troubling to those seeking a truly evenhanded approach to liberty in our land. The very use of quotation marks around the phrase “civil rights” relative to such persons might well persuade observers of the speaker’s animus toward the notion of granting such rights to groups whose conduct he finds abhorrent.

I would suggest this is most dangerous. Bible-believing Christians do believe homosexual practice to be sinful and antithetical to God’s will for men and women. But equal protection under American law is not only for persons holding to a religiously conservative worldview, nor is it limited to cultural conservatives in general. If Christians and other cultural conservatives wish protection for their right to denounce such behavior on the basis of their particular beliefs, they should confine such expression entirely to the realm of spirituality and voluntary choice, as they would with any other set of religious or cultural convictions. If religious conservatives were just as zealous in protecting the rights of those whose morality differs from theirs as they are in protecting their own right of free exercise and expression, much if not most of the antagonism attending these issues in society would likely be defused.

The homosexual issue is of deep moral import to Christians. And there are many other religious and theological disagreements with secular society and indeed within the Christian community. There are doctrinal disputes in Christian circles concerning biblical inspiration, the Trinity, the virgin birth of Christ, the law and salvation, and much more. Indeed, the biblical understanding of human sexuality is deeply rooted in biblical theology, and cannot easily be separated from it. Religious believers in our land hold deep theological variances on many issues, differences that rarely if ever find their way into the sphere of civil legislation. It is in this realm of theological and moral debate that the controversy over the rightness of homosexual practice belongs. It is better expressed in the voice of the evangelist than the judge-inquisitor. It is not within the purview of a nontheocratic state such as we have in America.

The notion that political and cultural liberals are presently seeking to “drive religious people from the public square” sounds a bit strange when one considers that some of the greatest champions of liberal politics in America have been strongly and openly religious. A survey, for example, of the presidential campaign speeches of the late U.S. senator George McGovern, in his 1972 campaign against Richard Nixon, finds numerous biblical references and the evoking of Christian themes.8 Describing the senator’s worldview in his chronicle of the 1972 campaign, the late historian Theodore White spoke of how “the rhetoric of morality and Scripture comes naturally to him,” and that “the evangelist lingered always in George McGovern” because of his Methodist upbringing.9

Numerous other examples of a similar nature could be cited from throughout American history. I believe it can be fairly stated that what has lately aroused such resentment of religion in the public square is not so much the acknowledgment of God or of transcendent morality by public figures, but rather, the intrusion of a religio-political agenda into matters where the state simply does not belong.

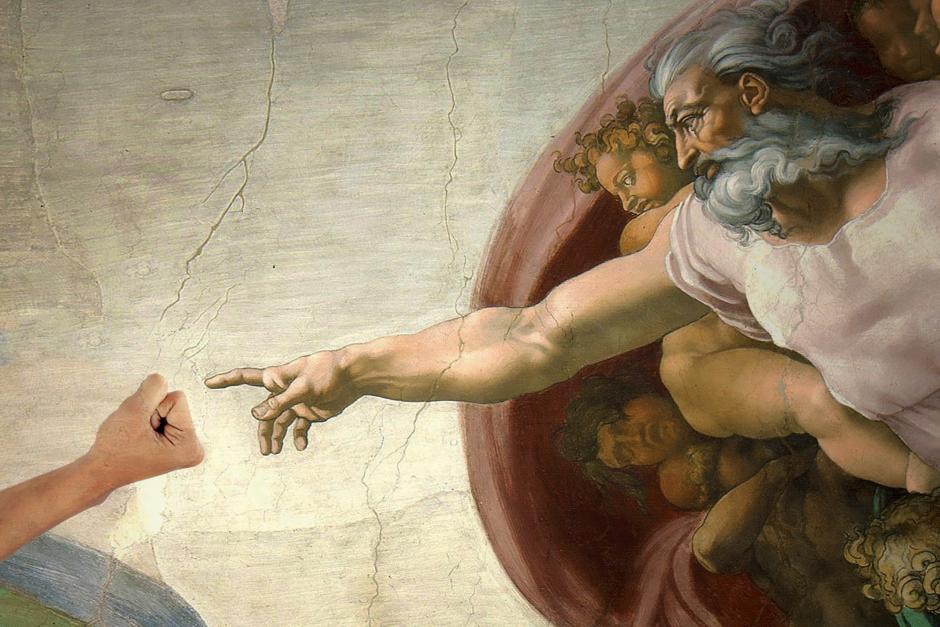

Two Trees

According to the Bible, God placed two trees in the primeval Garden of Eden—the tree of life and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil (Genesis 2:9). While Adam and Eve were forbidden to eat of the latter tree (verse 17), God still placed that tree within their reach, thus giving them a free choice. True religious liberty can do no less. Freedom of religion, as well as freedom from religion, must become the avowed agenda of religious liberty advocates, regardless of faith or the lack thereof.

Recently on ABC’s This Week With George Stephanopoulos, a panel of clergy and several others, including an atheist, were discussing the issue of gay marriage. Perhaps the signature observation of this discussion was made by Calvin Butts, pastor of the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, New York. Pastor Butts pointed out that while, according to Scripture, he cannot endorse the homosexual lifestyle or declare it to be morally correct, he is equally convinced that in a free country such beliefs cannot be legislated by civil law. The atheist woman on the panel responded that Pastor Butts’ comments were “music to my ears.” Religious liberty has a bright future in America if both the devout and the disbelieving can reach such agreement.

1 Cardinal Francis George, “Catholics and Latter-day Saints: Partners in the Defense of Religious Freedom,” address at Brigham Young University, Feb. 23, 2010, at http://speeches.byu.edu/?act=viewitem&id=1888&tid=7.

2 Hugh Hewitt, A Mormon in the White House? 10 Things Every American Should Know About Mitt Romney (Irvine, Calif.: Trilennium Productions, 2007), pp. 242, 243.

3 Dallin H. Oaks, address to the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty Canterbury Medal dinner, New York City, May 16, 2013, at www.becketfund.org/

wp-content/uploads/2013/05/elder-oaks-CMD-2013-Speech-PDF.pdf.

4 Robert D. Putnam and David E. Campbell, American Grace: How Religion Divides and Unites Us (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010), pp. 7, 75-80, 558-561.

5 Ibid ., p. 558-561.

6 Ibid ., p. 17.

7 Ibid ., p. 566.

8 An American Journey: The Presidential Campaign Speeches of George McGovern (New York: Random House, 1974), pp. 19, 30, 42, 112, 118, 136, 162, 205-212.

9 Theodore H. White, The Making of the President, 1972 (New York: Atheneum Publishers, 1973), p. 119.

Article Author: Kevin D. Paulson

Kevin Paulson is a much-published author, editor, and minister of religion. He writes from Berrien Springs, Michigan.