Back to the Future

Céleste Perrino-Walker March/April 2014Some decisions turn out to be epic. They may seem relatively small and inconsequential in the scheme of things at the time, but, later, when they are weighed on the scales of time and consequence, they turn out to be important benchmarks. We rarely foresee these decisions; they don’t often stand out in any way; instead they pass quietly without notice.

So it was for Kwasi Opuku-Boateng who worked as a grain inspector for the California Department of Food and Agriculture. He had acquired a temporary position and wanted to secure a permanent one. Then Opuku-Boateng applied for several positions, one of which was plant quarantine inspector, never dreaming that this would one day land him a place in history. A question on the application form asked if the applicant had a religious objection to sitting for an examination on Saturday. Although Opuku-Boateng responded affirmatively to the question, he later received notice of his examination date . . . scheduled on a Saturday.

When he received the notice, he immediately called the contact person listed, Diane Sheff, and she made arrangements for him to take the test on a Sunday instead. When he was later interviewed by Sheff and a man named Chuck Gray, he assumed that they were well aware of his inability to work on Sabbath because he had needed special accommodation to take his examination on a Sunday. During the interview neither Sheff nor Gray mentioned working hours or Opuku-Boateng’s religious beliefs. Gray’s main concern, which he put to Opuku-Boateng later over the phone, was whether or not he had a preference for any particular station assignment. Opuku-Boateng assured him that he did not—even when Gray cautioned him that some assignments had less desirable living accommodations than others. Opuku-Boateng’s only concern was that the station be close to a Seventh-day Adventist church.

The Problem Begins

On October 18, 1982, Opuku-Boateng was given the position of plant inspector at a border inspection station in Yermo, California. He was to report to work on November 2. Elated, he moved his family to Yermo. On October 28 he and the local Adventist pastor toured the facility, where Opuku-Boateng saw his new work schedule and realized with a shock that he was slated to work on November 14, a Saturday. He informed the acting supervisor, William Whitacre, that because of his religious beliefs he was unable to work from sundown on Friday to sundown on Saturday. He was told that unless he was willing to work on Saturdays his appointment wouldn’t be processed.

What followed was a brief tennis match of proposals, refusals, and counterproposals between local Seventh-day Adventist church representatives and the state in an attempt to accommodate Opuku-Boateng and allow him to keep his newly acquired position. By November 8, 1982, it was all over but the shouting. Howard Ingham, a program supervisor for the department, notified Opuku-Boateng that the appointment for his position would not be made because he could not frequently work from sundown on Friday to sundown on Saturday.

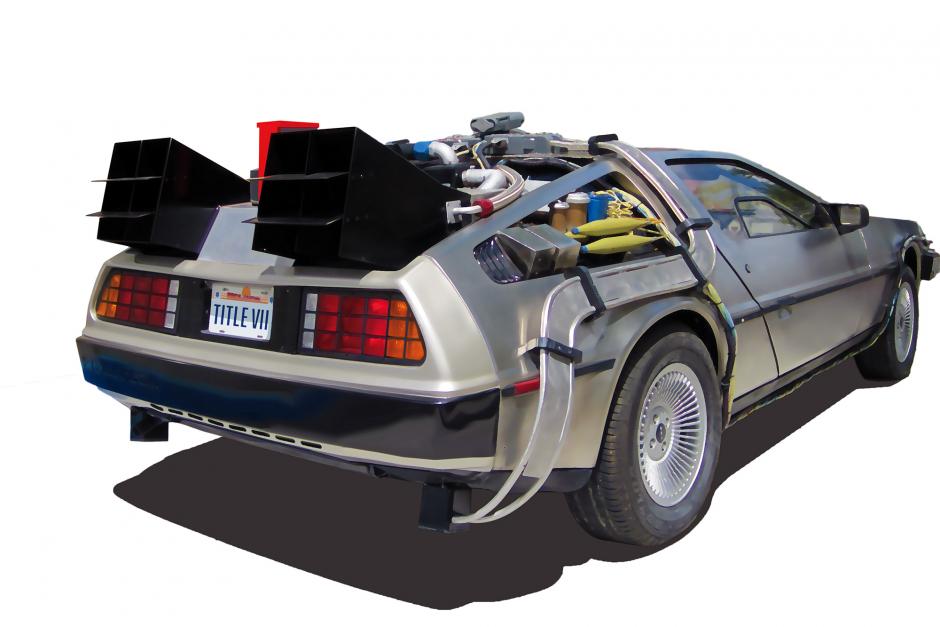

The appointment process was terminated, and Opuku-Boateng suddenly found himself without either the job he was looking forward to or the job he’d left behind. He had little choice but to file a complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. The district director determined that the state had made no effort to accommodate Opuku-Boateng’s religious beliefs and that there was reason to believe they had violated Title VII in refusing to hire him. In the end they gave him a right-to-sue letter, and the legal foray began.

The Crux of the Matter

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 is an employee’s protection against discrimination by an employer on the basis of religion: religion in this case including belief as well as all aspects of religious observance and practice. Cases are determined based on two criteria: the employee must first present a prima facie case for religious discrimination. This consists of proving that they have a sincerely held religious belief, that they notified the employer of the religious belief, and that they suffered an adverse employment action. If they can do that, the burden rests on the employer to prove that it did everything reasonable in its power to accommodate the employee’s religious beliefs and practices.

Opuku-Boateng methodically fulfilled every obligation required of an employee to make a case of religious discrimination. Because officials at the Department of Food and Agriculture had considered several options in an attempt to find a solution to Opuku-Boateng’s refusal to work on Saturdays, they felt that they had done their best to find accommodations for his religious beliefs. Claude Morgan, an attorney for the Church State Council who represented Opuku-Boateng initially, disagreed with them. “I contacted the State Department of Agriculture and spoke with a woman in the department who was their Equal Employment Opportunity officer. Her perspective was that they should be able to accommodate Kwasi, but each time they came up with an idea, the site manager down at the inspection station basically said, ‘No, we’re not going to do that.’ There’s no question at all that he flatly refused to work with the possible solutions.”

Round One

The court, however, did not see it that way. It ruled against Opuku-Boateng in favor of the state, asserting that while Opuku-Boateng had, in fact, established a prima facie case of religious discrimination, the state had also demonstrated that they could not possibly have accommodated his religious beliefs without undue hardship on the rest of the staff at the facility. This was to become the most scrutinized aspect of the case.

“It was a test of the obligations of the state of California and by inference other states as well,” Morgan says. “I think that makes it especially significant because a lot of the cases have been litigated against private employers. This is one that specifically looks at the duty of the state. The cases involving religious discrimination have shifted somewhat over the years as the U.S. Supreme Court has handed down rulings that clarified the limits on what kind of duties the Civil Rights Act imposes on employers. This is one case in which the line between duty to accommodate and undue hardship was meticulously litigated. We were pressing continually to try to establish that the state hadn’t made any effort to accommodate. I think that the fact that it was such a contested issue in the case makes it an important precedent for litigants, both for Sabbathkeepers, or any employee with religious beliefs, and employers who are looking for guidance as to what their obligations are.”

Round Two

Opuku-Boateng appealed the district court’s decision to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. The case was brought before three judges, who ultimately overturned the original decision and found in favor of Opuku-Boateng. Their judgment was based on their disagreement with the district court’s determination that the state had met its obligations to try to accommodate Opuku-Boateng’s religious beliefs. They asserted that at the very least the state should have retained him as a temporary employee until another position opened up in which his inability to work on Sabbath would not be a problem, or some of the proposed accommodation measures could be tested to determine whether or not they would rectify the problem. In their opinion the state had not gone nearly far enough in earnestly trying to accommodate Opuku-Boateng’s need for a single 24-hour period off each week. Their ruling stated: “The scheduling of shifts was not governed by any collective bargaining agreement, and the proposed accommodation would not have deprived any employee of any contractually established seniority rights or privileges, or indeed of any contractually established rights or privileges of any kind.”

In the federal circuit courts there are presently two different accommodation tests: the partial accommodation test and the complete accommodation test. Some courts hold with one test, and some with the other. There is a significant difference between the two. “The complete accommodation test ensures that the accommodation totally eliminates the conflict between the employee’s religious beliefs and the employment requirements,” Andrew J. Hull explained in an article for the Regent University Law Review. “The partial accommodation test does not necessarily eliminate this conflict. Rather, the test only demands that the accommodation be ‘reasonable’ in light of the circumstances, even if this requires a compromise of the employee’s religious beliefs.

“Many of the federal circuit courts hold to the complete accommodation test. But in 2008, the Fourth and Eighth Circuits both embraced the partial accommodation test. These two decisions mark a definitive split among the circuits over the protection afforded to employees to exercise their religious beliefs within the workplace.”2

The Ninth Circuit adopted the complete accommodation test that led to a final decision entered on May 19, 1997, a grueling 14 long years after the process had begun, not quite rivaling Jarndyce v. Jarndyce for longevity, but quite possibly setting a record all the same. “We’d been beaten down so long,” said Morgan. “It was a situation where you know you’re right, but you’re not sure anyone is ever going to acknowledge it.”

The Long Night

Opuku-Boateng could have given in to discouragement at any moment during the long trial process, but he didn’t. Although he no longer stood to regain his position, he continued to press on in the hopes that his struggle would help others who faced religious discrimination on the job.

The capacity for patience and hope during this unrelenting, tedious waiting period is not to be taken lightly. In fact, it’s a testament to the tenacity not only of the lawyers involved in the case, but of Opuku-Boateng himself. “It was quite an ordeal for him and his family,” Morgan says. “He was out of work; he changed careers a couple times. Some people get angry and belligerent and have tantrums over the injustice they’ve suffered. Kwasi was very stable about the whole thing. ‘Well,’ he’d say, ‘I just want to do what we can to work it all out, and we’ll hope that if it doesn’t help me, it will at least correct the situation so this won’t happen to someone else.’ Every time we discussed going forward with the appeal, Kwasi and his wife would pray about it, and then he’d tell me to go ahead. He kept saying ‘Let’s not give up; let’s keep trying.’ I have the highest regard for Kwasi’s Christian perspective and the spirit that he maintained throughout this whole process.”

Sabbatarians and others with strong religious convictions owe a debt of gratitude to Kwasi Opuku-Boateng and to his relentless legal counsel for their unflagging efforts to secure justice on his behalf, a justice that couldn’t benefit him but would continue to benefit others. When the verdict was given in Opuku-Boateng’s favor, Lee Boothby, who represented him, said, “The State of California was shocked and filed a petition for review by the United States Supreme Court, which turned down the appeal and thus, the Ninth Circuit decision is good law and held in favor of Kwasi and in favor of the need to accommodate religious beliefs.”3 And so an ordinary decision on an ordinary day became forever immortalized in legal history, providing a beacon of hope for all those who would come behind.

“Kwasi’s case is one of the most unique cases I’ve ever worked on in all my years in religious liberty,” Morgan says, “and I think it’s one of the most unique cases I’ve come across either through involvement or through research. He went through a long, convoluted, and very taxing ordeal to get to this verdict.”

“The importance of this case, from a legal perspective, is enormous,” says Alan Reinach, who has served as executive director of the Church State Council, the organization that first took on the case, for the past 20 years. “In most cases where employers fail to provide religious accommodations, the employer makes little or no effort to provide an accommodation. Because the facts were so well developed in Kwasi’s case, and because the State of California made minimal efforts to accommodate, the precedent puts all employers on very shaky ground unless they make much more substantial efforts to accommodate than the state did for Kwasi. We have settled literally dozens of cases after demonstrating that a company’s efforts were no better than those of the state in Kwasi’s case. Moreover, Kwasi’s case has been cited literally hundreds of times, and is certainly the leading case in the Ninth Circuit, covering 11 Western states, and a large slice of the American populace.”

- Kwasi Opuku-Boateng v. California; available online at http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/scripts/getcase.pl?navby=search&case=/data2/circs/9th/9416542.html.

- Andrew J. Hull, Complete or Partial Accommodation: An Analysis of the Federal Circuit Split Over the Duty of the Employer to Reasonably Accommodate the Religious Beliefs of the Employee, Regent University Law Review, Vol. 25, No. 1, 2012.

- The Seventh Day: Revelations From the Lost Pages of History; available online at http://www.theseventhday.tv/transcript5.shtml.