Beaten and Chastised

David J. B. Trim September/October 2021In late-seventeenth-century England, many children of nonconformist parents experienced the horror of religious persecution. In these rarely told stories of faithful suffering, we can trace the fragile roots of a growing social acceptance of a new idea: religious tolerance.

Religious liberty in the Anglo-American tradition has its origins in the seventeenth century, but emerged only out of religious war and persecution. During this period, for the first time since classical antiquity, there was genuine religious diversity in England. Added to the Protestant majority and Catholic minority were an increasing number of competing Protestant points of view, which eventually evolved into the ancestors of assorted modern varieties of Baptists, Congregationalists, Presbyterians and Unitarians, and the “Society of Friends,” or Quakers. But it was only at the very end of the century that diversity of opinion and practice in religion received limited official approval, when Parliament passed the Act of Toleration in 1689. For much of the century those who dissented from the official church’s position struggled for freedom to practice their faith, at first literally with sword in hand, and later by faithful witness in the face of imprisonment.

Among those who peacefully maintained their faith despite harsh punishment were children. Families, as well as individuals, were the targets of repression; boys and girls, as well as men and women, had to face the sanctions of a persecuting state.

Remarkably, youngsters, as did adults, often stood firm in the face of relentless physical and mental mistreatment. Their steadfastness was extraordinary because, even by the standards of what was an ordered, hierarchical society, children were indoctrinated to accept authority. From a very early age, “children received powerful incentives to obey.”1 Nevertheless, as adults increasingly questioned traditional positions in religion during the middle years of the century, children began to do likewise.

Regime of Intolerance

For a short period after the execution of King Charles I in 1649, diversity of opinion in religion flourished. Oliver Cromwell, Lord Protector of Britain from 1653 until his death in 1658, was strongly opposed to all forms of religious persecution.2 Under his rule, Protestant sects enjoyed unprecedented religious freedom, and even though anti-Trinitarians (forerunners of the later Unitarians), “Friends” (Quakers), and Roman Catholics faced official restrictions, they suffered less persecution than in the past—or future. For with the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660 began the most comprehensive and cruel program of religious repression in English history.

Parliament passed a series of laws aimed at crushing nonconformity: the Corporation Act (1661), the Act of Uniformity and the Quaker Act (1662), the Conventicle Act (1664) and the so-called Five Mile Act (1665). These made religious observances other than those of the official church illegal and set out harsh penalties for those who worshipped as conscience, rather than crown and Parliament, dictated. They also introduced sanctions against those who, even if conforming in practice to the rites of the Church of England, would not accept that the king was sovereign in religion. Although the laws were not enforced with uniform severity across the country, nor all sects persecuted equally harshly, between 1660 and 1689 dissenters were driven into poverty, prisons, and despair.

Voiceless Victims

As parents sought liberty of conscience and worship, their children were inevitably caught up in the reaction of church and state. Many endured the anxiety of keeping secret the meeting places of illegal conventicles, of worshipping, in the words of the Baptist historian E. A. Payne, in “lonely houses … cellars [and] haylofts,” or of being set as watchers “to give notice of the dangers of arrest.” The feelings of the children of London’s Seventh Day Baptists may be imagined when one of their pastors, John James, was arrested in 1661 and brutally executed by hanging, drawing, and quartering.3 In the 1730s one Presbyterian still remembered vividly how, in the early 1660s, his father was frequently “forced to disguise himself and skulk in private holes and corners,” rarely staying long in any one place, and he recalled that “the first public matter that I can remember I took any notice of” was a wave of arrests of Puritans and Roman Catholics in 1678.4 Yet psychological strain was not all that the children of England’s religious minorities had to endure.

Now, in theory, those under 16 years of age could not legally be arrested. The very language of the Conventicle Act, which declared illegal any religious gathering of more than five persons age 16 years and over, not of the same family, reveals that it was targeted at adults. But these illegal meetings tended to be held in private properties, and the children of participants were often present with them and so were caught up in their fate.5 Those arrested were widely regarded as “religious fanatics . . . whose actions upset the country both socially and politically,” and thus officers of the law were not overly concerned about what befell their prisoners’ children.6

For example, on December 7, 1662, a Quaker meeting in Worcestershire was disrupted by a party of militiamen.7 The lieutenant in command bade those present disperse immediately, and when one, Robert Baylis, did not move, “the lieutenant suddenly drew his sword at which the wife of the said Baylis, then big with child, was so terrified that she miscarried and was in great danger of her life.” Similarly, on June 17, 1665, the authorities in Northamptonshire showed “no interest in the fate of [the] dependent children” of 11 women dragged from a Friends’ meeting in the village of Findon. One “was great with child; another having a sucking child, and several poor widows, having diverse small children to care for.” Even so, they were fined severely and imprisoned for six weeks. In Bedfordshire, informers took the law into their own hands, attacking the Quaker Sarah Baker. Despite the fact that she had two sick children, they destroyed her “few household goods,” including the pan in which she was boiling milk for her children. In Cheshire, several Quaker widows had their household goods removed “till they had not a skillet to boil their children’s food in.”

The suffering of children in these cases, unborn as well as born, was unintentional, the result of persecution aimed at adults. As persecution of dissenters intensified, however, children increasingly did not merely witness persecution—they also had to suffer it.

Persistent Faith

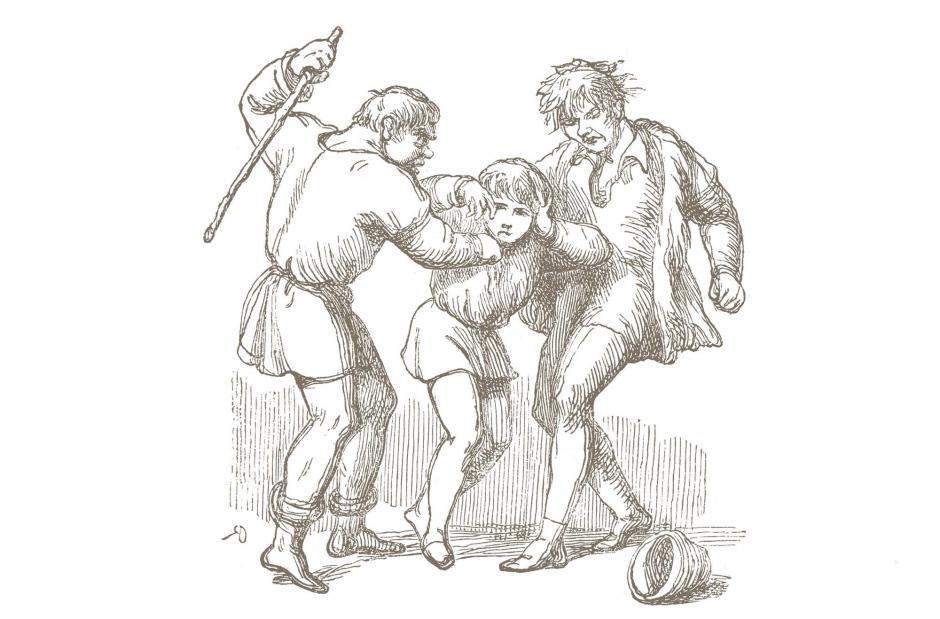

Some suffered simply because of their parents’ principles, afflicted by neighbors and peers. In 1671, 10 boys of Baptist families were expelled from Roysse School, Abingdon. An 8-year-old Quaker child, Thomas Chalkley, was beaten and stoned as he walked to school. “Pinching, beating and chasing became common forms of terrorizing children of dissenters.”

Most, however, endured persecution because they were active participants in their family’s faith. As persecution failed to end religious diversity, children found in attendance at clandestine church services were increasingly singled out for mistreatment.

In 1662 two Quaker boys age 13 and 16 were among those taken from London’s Mile End meeting and put for two hours in the stocks in Bridewell Prison. The same year, 11-year-old Rachel Fell was in the dock beside her Quaker mother, who was standing trial.

Some persecutors had children squarely in their sights. Although the law mandated children aged less than 16 could not face trial or be jailed, its provisions were often simply ignored. At Reading, in Berkshire, Quaker children suffered at the hands of William Armourer, a justice of the peace and equerry to King Charles II. After a meeting was disrupted on May 22, 1664, Armourer struck out with his staff and threatened the children present with imprisonment “if they came thither anymore.” The following month he “struck a lad, under age [that is, under sixteen], with a great cane and pulled him by the nose, so that his nose was much swelled.” On November 6, discovering children maintaining their own secret meeting in a granary, without adults, he had them seized and tormented them—“pricking some of them with a staff, having a sharp iron at the end, so that their flesh was very sore and black,” and others with a “sharp bodkin or packing needle.” A month later, finding the same children again engaged in a meeting, he threatened them with flogging. William Penn, who declared that Armourer was “always in armour for the devil,” also recalled that “for his diversion, and the punishment of little children, he [poured] cold water down their necks.”

In August 1666 three Quaker girls, Lydia Herfant, Mary Kent and Sarah Kent, were each fined a shilling and sent to jail, “where they lay a long time.” On June 5, 1680, six sons of Quaker parents were put in stocks at Bristol, while a number of girls were threatened with the same punishment. In addition, the boys had their hats forcibly removed from them and taken away for a time—a punishment for their Quaker habit of refusing to take their hats off to authority figures. In all, about 30 children were involved in the incident.

Two years later Bristol, the second-largest city in England, was again the scene of brutal—and this time sustained—persecution of Quaker children. Seven were confined in the city’s Bridewell Prison on June 11, but despite this and the imprisonment of all the adults, the children, unassisted, maintained their Meetings regularly over the next several months, “undergoing on that account many abuses with Patience.”

At the Bristol Quarter Sessions on July 16, Judge Tilly “caused five of the boys to be set in the stocks three quarters of an hour. A week later eight of the boys were put in the stocks two hours and a half.” In August Tilly personally, “with a small faggot-stick, beat many of the children, but they bare it patiently and cheerfully.” Beatings were continued three days later, this time with a twisted whalebone stick, and Tilly sent four boys to Bridewell Prison. They were released that night with threats of further whippings if they continued to meet.

On August 13, 1682, one lad fell afoul of John Hellier, a notorious persecutor. In the words of one historian, Hellier was “the most active and merciless enemy of nonconformists” in the area; contemporaries dubbed him “‘brutish Helliar’ and [described] his ‘diabolical rage’ against Quakers.” Although he was a lawyer, no legal niceties restrained him: he “beat Joseph Kippin, a young lad, about the head till he was ready to swoon; he also sent eleven boys and four girls to Bridewell.” Nevertheless, the children still would not yield to threats or persuasion, and stubbornly persisted in their faith.

The response of Bristol authorities was to up the ante. On the morning of August 27, six of the boys were sent away to London’s infamous Newgate Prison. Three months later two of them, the Watkins brothers—Joseph, age 14, and Samuel, age 11—were still confined in Newgate, as were two girls in their early teens, Mary Gibbons and Joanna Taylor. Back in Bristol, eight Quaker girls from 8 to 12 years old were in Bridewell. Thirteen more children were sent to Newgate and Bridewell prisons in September 1682. Those who remained in Bristol and were not imprisoned were subject to further mental and physical abuse.

Transformative Witness

All in all, as one scholar observes: “The story of children of persecution is a tragic account of pain inflicted on young lives, yet the children knew the possible price of their dissenting faith and were prepared to pay it.”8 But do the sufferings and steadfastness of youthful Quakers, Baptists, and other dissenters have any wider significance?

The answer is yes, because they helped create the climate in which the Act of Toleration became possible. The Act’s significance must not be overstated. It granted only limited liberty and only to Protestant denominations. Roman Catholics and Unitarians were excluded, while Baptists, Congregationalists, Presbyterians, and Quakers continued to endure informal persecution into the eighteenth century. It was, however, a critical first step—but why was it taken?

As John Coffey, an historian of toleration, has recently argued, the widespread view that proponents of deism, skepticism, and secularism were chiefly responsible for the advent of religious toleration is a fallacy. Thinkers such as Baruch Spinoza and Thomas Hobbes felt that confessional unity aided political unity and therefore argued that a prince could compel conformity to one faith—they did not particularly care which, since for them the arguments were not about what was right, but what was expedient. This cynicism is a world removed from the ordinary, often simple, people who refused to do what was expected of them by the church-state consensus in seventeenth-century England. Instead, they continued to believe and act as conscience dictated—as they thought was right.

This endurance of nonconformists and dissenters in the face of repression was vital. Once it became clear that these dissenters would not go away and would not conform, mainstream Anglicans faced a prospect of perpetually imprisoning, flogging, and even executing people who were in most respects good citizens, and with whom they actually agreed on most points of theology. It was a future they repudiated. England took the first step toward religious liberty not because the proponents of the radical Enlightenment had convinced the English nation to abandon religion, but rather because a Christian people decided that punishing others for differences of opinion, even on crucial points of doctrine, was unchristlike.9 They came to agree, even if unconsciously, with the essence of Quaker teaching as summarized in a classic historical account—“that Christian qualities matter much more than Christian dogmas.”10

All in all, then, the persecuted children of late-seventeenth-century England are of interest for several reasons. They are historical examples of patient and peaceful endurance of persecutory brutality. They also illustrate a point of enduring importance: that repression, once initiated, can take on a momentum of its own, leading to the harassment and punishment even of those originally meant to be excluded from the provisions of persecution. “Limited persecution” is always likely to be a contradiction in terms.

In addition, however, the faithful witness of nonconformist boys and girls in England during the reigns of Charles II and James II helped to shape—and to change—the views of wider society on persecution and toleration. For how could beating and imprisoning mere children ever be consistent with the teachings of Christ? It is notable that when, on one occasion late in 1682, the merciless John Hellier seized a 4-year-old boy “violently by the arms,” “lifting him from the ground” and threatening him with “You rogue . . . come no more to meeting,” he was stopped by “crying spectators.” The persecutors’ own severity was starting to discredit their efforts.11

The willingness of late-seventeenth-century English children to maintain their faith in the face of callous and often calculated brutality was thus a factor in the eventual shift in opinion that led to the rejection of persecution, and the official enactment of religious toleration in 1689. The physical pain and mental anguish endured by the young members of dissenting families helped to ensure that, eventually, people of all ages in Britain and North America would enjoy a more complete religious liberty.

1 Alison Wall, Power and Protest in England, 1525-1640 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), p. 114.

2 For a concise overview of Cromwell’s policy and the ideas underpinning it, see D. J. B. Trim, “Oliver Cromwell and the Intolerant Inheritance of America’s Religious Extreme,” Liberty, November-December 2006, pp. 12-15, 22, 23; January-February 2007, pp. 8-13, 26, 27.

3 E. A. Payne, The Free Church Tradition in the Life of England (London: SCM Press, 1944), p. 46.

4 Quoted in Mary Trim, “ ‘Awe Upon My Heart’: Children of Dissent, 1660–1688,” in D.J.B. Trim and P. J. Balderstone, eds., Cross, Crown and Community: Religion, Government and Culture in Early Modern England, 1400-1800 (Oxford, Bern, and New York: Peter Lang, 2004), pp. 261, 262.

5 E.g., see records of trials for breaches of the Conventicle Act, Hertford Quarter Sessions, October 1668, in Bodleian Library, Oxford, MS Rawlinson C. 719, pp. 1-6.

6 M. Trim, “Children of Dissent,” p. 275.

7 The examples of persecution and quotations from contemporary sources that follow are drawn from ibid., 260-270, and Mary Trim, “ ‘In This Day of Perplexity’: Seventeenth-Century Quaker Women,” in Richard Bonney and D.J.B. Trim, eds., Persecution and Pluralism: Calvinists and Religious Minorities in Early Modern Europe, 1550–1700 (Oxford, Bern, and New York: Peter Lang, 2006), pp. 190-192.

8 M. Trim, “Children of Dissent,” p. 269.

9 John Coffey, “Scepticism, Dogmatism and Toleration in Seventeenth-Century England,” in Bonney and Trim, eds., Persecution and Pluralism, pp. 149-176; cf. John Coffey, Persecution and Toleration in Protestant England, 1558–1689 (New York: Longman, 2000); Nicholas P. Miller, The Religious Roots of the First Amendment: Dissenting Protestants and the Separation of Church and State (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), chap. 2.

10 G. M. Trevelyan, English Social History (London, New York: Longmans, Green and Co., 1942), p. 267.

11 Quoted in M. Trim, “Children of Dissent,” p. 268.