Candor And Civility

Thomas J. Zwemer March/April 2008

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Paradoxically, nothing has shaped our ethos more than religion and learning. For centuries, the history of the church and the university have been on the same course—a seemingly endless stream of confrontations orchestrated by closed, vindictive, even murderous minds. Not even an ocean voyage could clear evil surmising from the minds of the "good church- and schoolmen of New England."

None other than the writings of Increase Mather, the first American-born president of Harvard, helped spawn the Salem Witchcraft Trials. In his 1684 paper An Essay for the Recording of Illustrious Providences,1 Mather presents an extended defense of the Puritan belief in witches and apparitions. He blamed the lustful and sinful ways of the Colonials for everything from the Indian wars to the unusual weather patterns. His polemic against the devil and sin served as a misguided theological defense for the "players" fomenting the Salem hysteria. After their deeds were done, and his own wife rumored to be named a witch, he presented a second paper, Case of Conscience , in which he tempered his former radical position. 2 Seven years after being appointed president of Harvard, he chaired a committee of seven that calmed the hysteria over witchcraft, and the hunt was abated and his wife spared.

More than 100 years later, Thomas Jefferson, a student of the Enlightenment, founded the University of Virginia as a secular institution with the stated principle of "illimitable freedom of the human mind." 3 Although Jefferson championed limitless freedom for the human mind, he cautioned against unbridled tongues and pen. 4

In keeping with Jefferson's vision, the University of Wisconsin-Madison, one of the first land-grant universities, set its mission to "provide a learning environment in which faculty, staff, and students can discover, examine critically, preserve, and transmit the knowledge, wisdom, and values that will help ensure the survival of this and future generations and improve the quality of life for all." 5

The freedom of the mind and the proper discipline and courtesy of the tongue and pen remain the purpose of academic freedom. Candor with civility in the areas of one's competence and commission are dear to the hearts and minds of the academic.

It wasn't until 1957, in the immediate aftermath of the McCarthy era, that the United States Supreme Court issued its first opinion in support of academic freedom. 7 Sweezy v. New Hampshire:

"Paul Sweezy taught American economics with a socialist twist. He campaigned in New Hampshire for Henry Wallace's run for the presidency on the Progressive Party ticket. While in New Hampshire, he gave a lecture on Marxism at the University of New Hampshire. Attorney General Louis C. Wyman subpoenaed Sweezy, demanding he reveal his personal political view and political activities. Rather than "take" the Fifth Amendment, Sweezy refused to comply with the subpoena on the basis of the First Amendment. Of course, he was charged and convicted of contempt of court. It was finally resolved by the United States Supreme Court in favor of Sweezy."

It took another 10 years in the midst of the Vietnam era for the Court to reaffirm that right.

In the second of two landmark cases, Keyishian v. Board of Regents , 8Justice Brennan in delivering the opinion of the Court wrote, "The classroom is peculiarly the 'marketplace of ideas.'" 9

Keyishian was an instructor at the University of Buffalo when it became part of SUNY (State University of New York). As a state employee, he had to sign a loyalty oath. He failed to sign by the end of his annual term and was thus terminated. He took legal action. The case finally reached the United States Supreme Court. A major issue being addressed in the 1967 session was the use of loyalty oaths in faculty employment. Justice Brennan expanded the Court's opinion by writing: "Our Nation is deeply committed to safeguarding academic freedom, which is of transcendent value to all of us, and not merely to the teachers concerned. That freedom is therefore a special concern of the First Amendment, which does not tolerate laws, that cast a pall of orthodoxy over the classroom" (italics added). 10

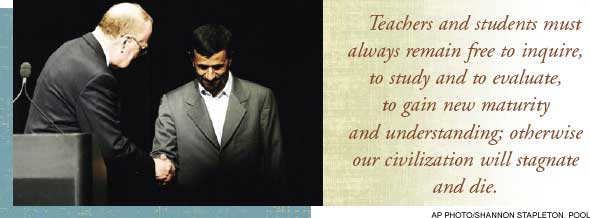

Justice Brennan continued with a quote from Sweezy v. New Hampshire , 354 U. S. 234, 250 (1957): "'No one should underestimate the vital role in a democracy that is played by those who guide and train our youth. . . . Teachers and students must always remain free to inquire, to study and to evaluate, to gain new maturity and understanding; otherwise our civilization will stagnate and die.'" 11

But these concepts did not spring full bloom from the pen of the associate justice. It took 40 years of development by the American Association of University Professors to capture the attention of the Court.

The AAUP was founded in 1915 by John Dewey of Columbia, formerly of the University of Chicago, and Arthur Lovejoy of Johns Hopkins. The provocation was fourfold: (1) the dismissal of the noted economist Edward Ross of Stanford University simply because Mrs. Stanford didn't agree with his views on immigrant law and railroad monopolies; (2) the dismissal in 1915 of Edward Bemis from the University of Chicago for advocating the public ownership of railroads and utilities; (3) the dismissal of Scott Nearing from the University of Pennsylvania because he publicly agitated against child labor; and (4) the baseless retaliation against German- and Austrian-educated professors during the First World War. At least 23 professors lost their jobs simply because they held doctorates from German and Austrian universities. 12

Because of the overreaction to German academics during the 1914-1918 hostilities, the American universities were particularly restrained in their criticism of German scholarship during the 1933-1945 Nazi perversion of scholarship.

To illustrate the changing academic/political environment, one need but follow the comments of Nicholas Murray Butler, Nobel Prize winner and president of Columbia University for the unprecedented tenure from 1901-1945.

In 1917 he wrote: "There is no room for any among us who are not with the whole heart and mind and strength committed to fight with us to make the world safe for democracy."

Dr. Butler followed these words with firing three German-trained faculty members.

However, by 1935, he wrote: "The world cannot do without [the intellectual leadership] of Germany, no matter how preposterous and reactionary may be its ruling policies and doctrines at the moment."

It is interesting to note that Dr. Butler's 1935 statement was made in spite of the letter to him from George Norlin, former president of the University of Colorado, who stood in the door against a KKK governor. In 1935 Norlin was the Theodore Roosevelt professor of American History and Institutions at the University of Berlin when he wrote to Dr. Butler at Columbia:

"Truth was being made to order in Germany resulting in mental prostitution and a form of madness."

In contrast, Lawrence Lowell, president of Harvard and a contemporary of Dr. Butler's, when threatened with the loss of a $10 million bequest unless he fired a pro-German professor, said:

"If a university or college censor what its professors may say, if it restrains them from uttering something it does not approve, it thereby assumes responsibility for that which it permits them to say. This is logical and inevitable. If the university is right in restraining its professors, it has a duty to do so, and it is responsible for whatever it permits. There is no middle ground. Either the university assumes full responsibility for permitting its professors to express certain opinions in public, or it assumes no responsibility whatever, and leaves them to be dealt with like other citizens by the public authorities according to the laws of the land."

Unfortunately, the courage of the American Association of University Professors in fighting senseless retaliation during the First World War was absent during the hyper-vigilance of the early Cold War years. Scores of faculty lost their jobs in that reign of terror with hardly a peep out of the AAUP. It wasn't until Senator Joe McCarthy of Wisconsin was discredited in June 1954 that the AAUP took of advocacy in the cases of Sweezy and Keyishian.

The burning issue before the academy remains: Can we, as Jefferson so desired, speak softly yet carry a big idea?

Since 9/11, we are again in times of tension and suspicion. Words, behavior, and associations are carefully monitored, and for good reason. Yet to prevent a fifth or sixth round of witch hunting, let us remind ourselves not only of our constitutional rights and duties, but as professionals "to do no harm!" We would do well to remind ourselves of the standards of freedom and civility that teachers have established in the spirit of Thomas Jefferson. Sections b. and c. of the American Association of University Professors Standards state:

"Teachers are entitled to freedom in the classroom in discussing their subject, but they should be careful not to introduce into their teaching controversial matter which has no relation to their subject. Limitations of academic freedom because of religious or other aims of the institution should be clearly stated in writing at the time of the appointment.

"College and university teachers are citizens, members of a learned profession, and officers of an educational institution. When they speak or write as citizens, they should be free from institutional censorship or discipline, but their special position in the community imposes special obligations. As scholars and educational officers, they should remember that the public may judge their profession and their institution by their utterances. Hence they should at all times be accurate, should exercise appropriate restraint, should show respect for the opinions of others, and should make every effort to indicate that they are not speaking for the institution."

If academic freedom is to survive, it needs to be perceived as the champion of civil discourse in the pursuit of great ideas. Nevertheless, it is the crass affronts to civility that make the news and the courts. Unfortunately, issues of great pith and moment seldom find their way into federal courts.

In the time between the end of the Vietnam conflict and 9/11, the courts have been largely occupied by the peripheral, the trivial, the contentious, the venial, and the vulgar aspects of First Amendment issues. A prime example is Urofsky v. Gilmore, U. S. Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals : 13

"Melvin Urofsky and five others employed by various public colleges and universities in Virginia brought suit against the governor of the state of Virginia challenging the constitutionality of the Virginia statute limiting or restricting state employees from accessing sexually explicit material on state-owned or leased computers. The district court found in favor of the plaintiffs, agreeing that the statute infringed on the state employee's First Amendment rights. The Fourth Circuit Court reversed the finding of the district court, stating that the six professors were state employees not acting on a bona fide approved research project, nor were they acting on an issue of public concern. Therefore, the commonwealth as an employer could regulate their "speech" in this context without infringing upon any First Amendment protection."

Vulgarity was the issue at the turn of the century. John Bonnell lost his appeal to the Sixth Circuit Court for using gratuitous, repetitive vulgarities and obscenities in his English classes at Macomb Community College. 14 Kenneth E. Hardy won his case on appeal before the Sixth Circuit Court for using "trigger" ethnic words in one class period on interpersonal communication. 15

Of course, the courts have limited ability to choose their litigants. Thus the courts, in recent academic freedom cases, have essentially established the lower reach of academic speech. Law can only establish a bottom line. It remains for the academy and its champions, and not the law, to demonstrate the higher reaches of self-expression.

Prior to 9/11, Dr. Anthony Diekema, president emeritus of Calvin College, pointed to four causes for the diversion of the academy from preparing a new generation to explore, to examine, to poke, to prod, to challenge, and to question issues of great pith and moment: "1. The ever present ideological enthusiasts who have plagued the academy since Mather, 2. The political correctness kick that is championed by single-issue special interests, 3. Postmodernism that rejects objective evidence and embraces power, and 4. The drift of the AAUP from the founding principles of John Dewey et al." 16

The importance of the Sweezy and Keyishian decisions looms larger in the face of the hypervigilance of ideological enthusiasts in our post-9/11 environment. This "search and destroy mind-set" is once again threatening to place us under a "pall of orthodoxy."

Never in the history of the United States of America have self-discipline, civility, and objectivity been more essential than in a time when "terror stalks the land." Fear haunts the White House, the halls of Congress, city hall, and the schoolroom. Objective thinking is at a premium. We must remember that religious liberty is but a subset of civil liberty, which has as its substrate the kinship of all mankind. To berate other belief systems is to foment strife—even civil war! Some may call it a crusade, an intervention, even redemption, but at the point of a gun or a stockade?

The current international crisis poses serious academic problems. It pervades history, geography, energy, government, sociology, psychology, the graphic and the performing arts. Moreover, it has explicit religious components attended by outspoken Christian, Hebrew, and Islamic proponents who find bloodletting a divinely appointed mission.

We face the question: Can the Academy carry out its civic responsibilities by merely pledging allegiance to the flag? Surely not, but how far can it go in parsing out the parameters of the present conflict without trampling on the "civil rights" of those of contrary view? Let us hope we never arrive at a "Committee of Public Safety!"

When we have university presidents speaking provocatively toward invited guests, can tyranny be far behind?

Our problem is not the bombast of desert chiefs, the greed of captains of industry, or the forecast of every student of Schofield. Our problem is safeguarding civility and due process while under extreme duress. With a form of religion at the core of the problem, with the public classroom so restrained, with the press exuberant but easily led, and with the legislature in irons of its own making, can we reasonably expect the courts to withstand the tsunamis of civil cases flooding their doors?

The answer lies in the First Amendment. It is now time to act toward one another as if we were sharing the same foxhole. Close quarters require the maximum of civility and courtesy in order to survive. We did it without fanfare for ten days to two weeks after 9/11, until the ideologues threw their personal agendas into the cauldron.

"It's a small world after all!" Let us be neighbors in our conversation, in our work, in our play, in our worship, and certainly in our civic duties. After all, we each pledge allegiance to liberty and justice for all!

Thomas J. Zwemer is vice president emeritus for academic affairs at the Medical College of Georgia in Augusta, Georgia.

1 Robert Middlekauff, The Mathers: Three Generations of Puritan Intellectuals, 1596-1728 (Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1999).

2 "Increase Mather" www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/salem/asa_inc.htm

3 Edwin S. Gaustad, Sworn on the Altar of God: A Religious Biography of Thomas Jefferson (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1996).

4 University of Wisconsin-Madison Almanac , p. 3, 2003.

5 www.wisc.edu/about/history

6 Land-Grant Colleges and Universities www.nrcs.usda.gov/technical/land/meta/m2783.html

7 Sweezy v. New Hampshire, 354 U.S. 234 (1957).

8 Keyishian v. Board of Regents, 385 U.S. 589 (1967).

9 Ibid., 385 U.S. 589, 603 (1967).

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 AAUP Statement of Principles 1940/1970 www.aaup.org/com

13 Urofsky v. Gilmore, 216 F.3d 401 (4th Cir. 2000).

14 Bonnell v. Lorenzo et al., 241 F.3d 800 (6th Cir. 2001).

15 Hardy v. Jefferson Community College et al., 260 F.3d 671 (6th Cir. 2001).

16 Anthony J. Diekema, Academic Freedom and Christian Scholarship (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2000).