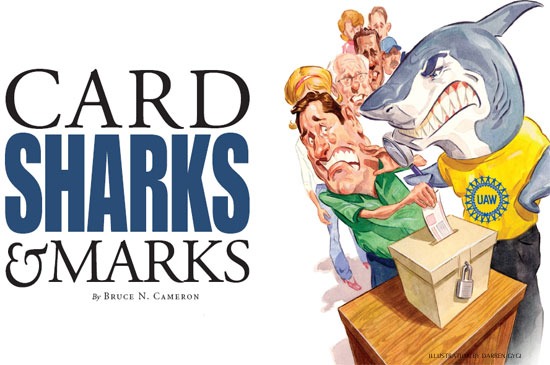

Card Sharks And Marks

Bruce N. Cameron January/February 2006

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

United States Constitution Fantasy Fight: O'Reilly v. Tyson.

If your favorite political color is blue, fantasize flipping Bill O'Reilly into a boxing ring with Mike Tyson. If your political preference runs to red, drop Dan Rather into the ring with Mike. Whatever your political orientation, you can be pretty sure Mike is going to win. Just in case you think "Bill/Dan" might have an outside chance of tricking Mike into biting off his own ear, improve your odds a bit more by having the referee agree to hold "Bill/Dan" while Mike takes his best shot.

However much you might enjoy your least favorite pundit being subjected to such a one-sided matchup, you know you are not going to be reading about this fantasy fight anytime soon in the pages of Sports Illustrated.

The bad news is that this kind of lopsided fight is going on right now, and it is not fantasy. These fights involve average workers, and you can read about these mismatches in the Daily Labor Report.

These "Bill/Dan" versus Mike contests are referred to as "neutrality and card check" agreements. Organized labor, its lawyers, and its politicians are doing their best to make them a regular feature of our national labor laws. Employees who value freedom of choice, aided by the National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation, are litigating to outlaw these agreements..

Labor Law

To better understand this current war over employee freedom, here are a few facts about U.S. labor laws. Employees have the right to join a union, and an equal right to refrain from joining a union, without jeopardizing their job.

Rarely, however, are employees allowed to make this decision on their own. In the usual case, the employees on each side of the issue have powerful allies. Those employees who want a union have available to them the huge resources of organized labor. This includes full-time union staffers, union printing presses, and union organizing experience. This professional union help is completely lawful.

The result is usually a pretty fair contest. Employees get to hear both sides and express their decision in a secret-ballot election. No one is looking over their shoulder when they vote.

Fair Fights No Longer Serve Unions

After decades of applying this "fair fight" system, unions discovered that employees generally decide they do not want to be represented by a labor union. Even worse for unions, the belief that labor unions are more trouble than they are worth appears to be snowballing. Since 1953 the percentage of private sector employees who voluntarily chose labor unions has dropped from 31.9 percent to just 7.9 percent today.

What is needed, according to organized labor and the politicians who get reelected with their help, is a new set of rules. Enter the "Bill/Dan" versus Mike fantasy fight. The first order of business is to strip employees who prefer to work union-free from any aid from sympathetic employers. Lacking any organization or funding for their union-free views, these employees find themselves in a contest with pro-union employees and professional union organizers who are aided by the money, staff, and media of organized labor.

Why would any employer want to vacate the field of contest and leave employees with union-free preferences to fend for themselves against big labor? The answer is "to stay in business."

Consider the present American automobile industry. Ford, General Motors, and DaimlerChrysler all bargain with the United Auto Workers (UAW). The employees of many of the parts suppliers for these car companies, however, are not represented by a union. To curry favor with the UAW, these three car companies signed a "Good Corporate Citizenship" agreement that pressures their suppliers to sign UAW "neutrality and card check" agreements. The nonunion employees of these parts suppliers, playing the role of "Bill/Dan" in our example, are now left alone with the UAW, which is now free to play the role of Mike Tyson.

Recall that in the fantasy fight the referee held "Bill/Dan" to ensure an already predictable outcome. The same is true with neutrality and card check agreements. Employers give unions access to their facilities and aid union organizers in soliciting workers' support. Worse, some employers agree to "captive audience" speeches by the union. During worktime, employees are required to attend what is essentially a union rally at which union and company officials explain what a very good thing it would be for the union to represent employees.

You would think that with the full resources of organized labor pitted against those individual employees who do not want a union, and with the employer conducting worktime union rallies, the outcome of the union election would be certain.

Apparently not. Even under these circumstances, union officials are not content with elections that are premised on the basic democratic principles of our political system. Neutrality and card check agreements give unions a loophole around the secret ballot.

Union Label Ballots

While employees have historically been able to express their opinion on union representation through a secret-ballot vote, organized labor is fighting to move employees out of the shelter of the ballot booth and into the alley, where union agents can "help" them with their vote. Neutrality agreements substitute the signing of a "union authorization card" for the casting of a secret ballot on the question of union representation. This is called a "card check."

This is where the "card sharks" enter the water with employees. Over the many years of my litigation, the legal team with whom I work has represented employees who were shot, beaten, had their homes burned or riddled with bullets or stones, their property destroyed, their families threatened, or their pets killed. One employee found a severed cow's head on the hood of her car.

Card checks allow the same friendly union fellows with a historical connection to mayhem against dissenters to "discuss" with employees whether or not they will sign the union card. Signing the card is a vote for union representation. The employee's signature on the card, if all goes well from the union's perspective, will take place while the employee and the friendly union fellow(s) are standing next to each other.

To be fair, the vast majority of my litigation does not involve union violence. There is no reason to believe that if unions are allowed to substitute "card check" for a secret ballot, employee signatures will regularly be the result of the fear of pistol-whipping.

It is reasonable, however, that the card sharks will use pressure to convince employees to sign a card for the union—and not just pressure at work. As part of a "neutrality agreement," employers provide the home addresses of employees. Consider a sworn declaration from an employee in litigation pending before the U.S. Supreme Court:

"[After my employer gave the union my name and home address], two union representatives came to my home and made a presentation about the union. They tried to pressure me into signing the union authorization card, and even offered to take me out to dinner. I refused to sign this card as I had not yet made a decision at that time. Shortly thereafter, the union representatives called again at my home, and also visited my home again to try to get me to sign the union authorization card. I finally told them that my decision was that I did not want to be represented by this union, and that I would not sign the card.

"Despite the fact that I had told the union representatives of my decision to refrain from signing the card, I felt like there was continuing pressure on me to sign. . . .I also heard from other employees that the union representatives were making inquiries about me, such as asking questions about my work performance. . . . Once, when I was on medical leave and went into the hospital, I found that when I returned to work the union representatives knew about my hospitalization and my illness."

This kind of close and personal lobbying would make the average voter cringe—even if it ended in a secret ballot. But, under the card check system, the "ballot" is cast under the watchful eye of union representatives.

Proof of the hands-on approach to card check appears on the face of the current UAW card:

"It is UAW policy that if an employee requests the return of their authorization form prior to the form being sent to the Neutral Third Party, the form will be destroyed in the presence of the employee."

The potential for foul play and violence in the card check system is not simply based on organized labor's unfortunate history of violence. One union partisan soliciting union cards told a reluctant employee that "the Union would come and get her children and slash her car tires."

The specter of violence is part of current news. Jeff Ward is an employee who wants to be union-free. When his employer and the UAW entered into a neutrality agreement, he filed a legal challenge that resulted in their giving up the agreement in favor of letting employees vote the old-fashioned way—with a secret ballot.

But, while Jeff's work to restore a secret ballot was ongoing, in March 2005, flyers started circulating in the plant that read in part: "Jeff Ward lives here. Go tell him how you really feel about the union." The flyers listed Jeff Ward's phone number and provided detailed driving directions to his home.

The benefit of a secret ballot is that no one knows how you voted. There is no need for union supporters to call you or make personal visits to your home to share how they really feel about your vote.

It Could Happen in America

Most of the time when something seems grossly unfair, we don't worry because it could not happen in America. Don't be so sure. Organized labor already has the political and judicial muscle to exempt itself from most of the basic human rights we take for granted.

What is your most fundamental human right? The right to be free from violence? Did you know that for more than 30 years unions have been exempt from federal prosecution for "the use of violence to achieve legitimate union objectives." Imagine if Democrats or Republicans got immunity from federal prosecution for "the use of violence to achieve legitimate party objectives"—such as getting you to vote for John Kerry or George Bush. Impossible, right? Not for labor unions.

Unions also have a pass on damaging reputations. In Old Dominion Branch No. 496, National Assn of Letter Carriers v. Austin, 418 U.S. 264 (1972), the Supreme Court gave labor unions the same license to defame individual workers—private citizens—as the press is given to defame public figures such as the president of the United States.

For more than 150 years one basic human freedom in the United States has been that no citizen can be required to join or financially support a church. The general rule is that no one can make you join or financially support any purely private organization.

On this basic human liberty, unions are given federal immunity. Unless specifically prohibited by state law, federal law allows unions to negotiate contracts that require that employees either join the union or pay compulsory fees as a condition of employment.

Unions hit the perfect trifecta when it comes to denying the most basic human rights of employees under federal law. They can violate their person, steal their reputation, and take their money.

The fight to keep unions from taking away yet another fundamental right—a secret-ballot vote—is going to be tough. Where is that Tyson guy when you need him?

___________________________

Bruce N. Cameron writes from Springfield, Virginia. He is a litigator for the National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation and directs its Freedom of Conscience Project. He is active in writing and lecturing on the topic of religious freedom and constitutional law.

1 29 U.S.C., Sect. 157.

2 29 U.S.C., Sects. 152(3), 157, 158(c).

3 N.L.R.B. v. Gissel Packing, 395 U.S. 575, 618 (1969); 29 U.S.C., Sect. 58(c).

4 Friedman, Labor Unions in the United States, E.H.Net Encyclopedia, http://eh.net/encyclopedia/?article=friedman.unions.us (Table 4).

5 U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2005/02/lmir.htm#2 (Feb. 2005).

6 Since 1982, UAW membership has been in a free fall from 1.14 million (http://appropriations.senate.gov/releases/messenger%20testimony.pdf [note 11]) to 625,000 at the end of 2003 (www.thecarconnection.com/index.asp?article=7265).

7 See, for example, www.uaw.org/contracts/99/saturn/sat07_2.html. Mike Taylor, a former long-term employee of the National Labor Relations Board, reported, "In a neutrality clause situation a corporation cannot use second- or third-tier suppliers, even though they are not involved in a labor dispute, unless they also agree to card checks and sign neutrality clauses" (www.gentrylocke.com/attorneys/photo/100_Union+Article+BRBJ.pdf).

8 Dana Corporation and UAW Letter of Agreement, August 6, 2003, Article 2.1.3.5.

9 Ibid., Article 3.

10 Ibid., Article 2.1.3.1.

11 Declaration of Faith Jetter in Support of Brief Amici Curiae to the U.S. Supreme Court in Sage Hospitality Resources v. Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees Union, Local 57 (No. 04-1216, April 2005).

12 www.nrtw.org/20050215letter.pdf (see form following

p. 17).

13 HCF, Inc., 321 N.L.R.B. 1320 (1996).

14 www.nrtw.org/b/nr_386.php.

15 U.S. v. Enmons, 410 U.S. 396, 400 (1973).

16 Virginia's 1786 Act for Establishing Religious Freedom ended compulsory support for churches in Virginia. However, compulsory support in the United States did not end until 1833, with the disestablishment of the Congregationalist Church in Massachusetts (Pfeffer, Church State and Freedom, p. 253 [Beacon Press 1967]).

17 Twenty-two states, called right-to-work states, prohibit compulsory union support (www.nrtw.org/rtws.htm).

18 Abood v. Detroit Bd. of Educ., 431 U.S. 209 (1977); Ellis v. BRAC, 466 U.S. 435, 455 (1984); Communications Workers v. Beck, 487 U.S. 735 (1988).

___________________________