Changing Times

Lincoln E. Steed November/December 2008

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

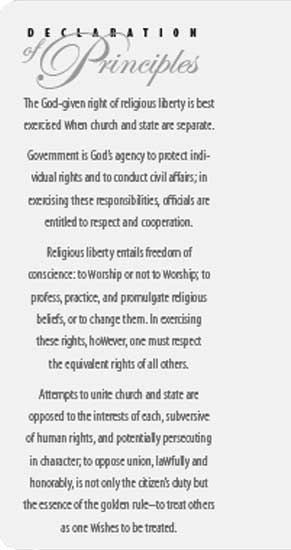

First a backup, to keep my job and our readership. Liberty has to speak to issues of great political import, and indeed call the religious liberty implications as we see them. However, we cannot, dare not, be partisan. We cannot buy into or automatically be opposed to any political agenda. We cannot support any political party. And I write this not because to do so might lose our church-related nonprofit status—not even because it would deny our overarching principle of the separation of church and state—but because it would betray the truest principles of religious liberty. If religious liberty—one of those "self-evident" realities—supposes anything, it is that it transcends political loyalty. It is a divine right and relates to the higher sphere. Why demean it by partisan squabbling?

Another backup—not to run over your sensibilities again but to explain the title—in case it was so obvious as to seem as meaningless as most political slogans. Correct me if I am wrong, but it seems to me that both major candidates in the U.S. presidential election ran on a platform of change. One as the candidate of change, the other promising "change." The electorate will obviously decide what that means. But I have news for those who base their perceptions on political "chatter": change is here to stay. "The times they are a changing" is not just a protest refrain from another era but the narrative to our careening times.

How to characterize our times? As I write this the media is saturated with news of Hurricane Ike and the biggest single point drop on the Dow Jones since 9/11. Terrors without and within it seems. And while the faraway troop surge in Iraq seems to have accomplished something, the increasing numbers of desert-fatigue-outfitted soldiers in airports and public places creates the ambience of war. Things are not quiet on the Western front!

But of course religious freedom is safe here, you might say.

And I can certainly praise God that no one has yet forbidden me to worship at my church, has yet locked its doors, or has yet denied my right to speak of my faith. I have not even been criticized for my faith outside of my own faith community. (There's often more criticism of one's faith view and particulars within a religious community than without.)

The reality is that judging an overall situation by my own case can be very misleading.

The reality is that we are in a global war against an extremist view of a particular religious view.

The reality is that a form of civil religion is rapidly coalescing around American exceptionalism.

The reality is that religious bona fides were a defining element in the lead-up to the 2008 election. "No religious test for public office" seems far distant from the attacks on the Mormonism, Pentecostalism, and supposed Islamic connections of various candidates. We have come to see religion as a very important marker of public policy, if for no other reason than that so many have pursued a religiously oriented public policy.

The reality is that the once suspect public funding of church activity has moved from constitutional debate to a bipartisan rush to facilitate the new entitlement. After all, in Hein the Supreme Court justices denied taxpayer standing to challenge Faith-Based Initiative funding.

The reality is that a triumphalist form of state religion seems to have infected even U.S. military training institutions. The reality is that a particular prophetic scenario for end-time events in the Middle East seems to be adding an extra frisson to overseas missions. Great powers are always tempted to use military power—some may argue that they are required to. But salting the need with religious justification always risks devaluing faith and extending the conflict.

The reality of our present economic meltdown is that it found much of its genesis in a theology of wealth, sprinkled as a type of holy water on the capital markets and called a moralizing force. We seem to have forgotten that man is a rather selfish creature; and that just as the supposed workers' paradise of communism foundered on inequality, so aggressive capitalism can dry up even a trickle-down effect of concern for the man on the street.

The reality of our present spiritus

mundi—in the United States at least—is a willingness to agree to any mistreatment of fellow human beings, so long as they are accused terrorists, prisoners of war, detainees under suspicion of antisocial sympathies, murderers; and one gets the impression from talk radio that included on the list are political opponents. In short, the old dislikes have now been imbued with the state theology of evil. No wonder waterboarding seems mild! Such deserve the eternally burning fires (not really in my Bible, by the way). Tell me how the rabid, constantly repeated radio talk show denunciations of this type differ from the barrage of radio incitements that goaded Rwandans to genocide and I'll accept only answers that acknowledge a difference of degree and frequency, not of underlying message. This is not the type of civil discourse that protects religious freedom. When the other is theologically recategorized as nonhuman—as was done during the years of slaveholding, for example—even lynching takes on a redemptive aspect in moments of crisis.

Back in the Vietnam era, when vast crowds of war protestors flooded the Washington Mall, there was active debate about the direction our society was taking. In retrospect we can see, I think, that it was healthy to have a public debate about the issues of life and death in our world. Maybe some of the protesters just wanted to shirk their civic duty. Maybe some of the National guardsmen unthinkingly equated their longer-haired peers with Soviet menace. The upshot was a reasonable recognition that the United States was on a course that was at odds with its own creation myth.

Is it significant that back in that era religious yearnings and secular dissent came together in the Jesus Movement—a somewhat new age, free-form Christian revival? Is it significant that this time around dissidence is both legally frowned on and eschewed by a passive population stirred on many fronts by a sense of disease but not clear about the issues? Is it significant that this time around our spiritual yearnings settle so much on the state?

That, I hold, is a change we should regard with deep dread. It is a societal shift that is dragging our very mindset away from the constitutionally mandated disestablishment of religion.

Back a few years ago, I often saw bumper stickers carrying the message "America: love it or leave it." I saw them on Hondas, Cadillacs, and pickups. Thankfully that was actually an era when we would embrace the refugee who had crossed a wall under gunfire. Usually they were leaving a country that was giving them such an ultimatum. They came to the U.S. because they believed that in this new world context they would have freedom to differ on all the important issues: politics to be sure, but worldview, culture, and religion equally.

More recently I have spotted bumper stickers with the message "My country, right or wrong." I do not find these so much belligerent as misguided. After all, these might still be England's North American colonies if that had been the attitude to perceived injustice. It certainly confuses the admirable trait of patriotism with a nationalism that can be enlisted to almost any cause.

I am still hoping to see a bumper sticker with something to this effect: "My Country—setting right the wrong."

Change is here to stay, even as it moves on. Let's make sure that we take our moral compass with us on our journey.

Lincoln E. Steed, Editor

Liberty magazine

Please address letters to the editor to

lincoln.steed@nad.adventist.org

Article Author: Lincoln E. Steed

Lincoln E. Steed is the editor of Liberty magazine, a 200,000 circulation religious liberty journal which is distributed to political leaders, judiciary, lawyers and other thought leaders in North America. He is additionally the host of the weekly 3ABN television show "The Liberty Insider," and the radio program "Lifequest Liberty."