Christian Nationalism and the Art of Flossing

Bettina Krause September/October 2023An interview with sociologist and author Andrew Whitehead.

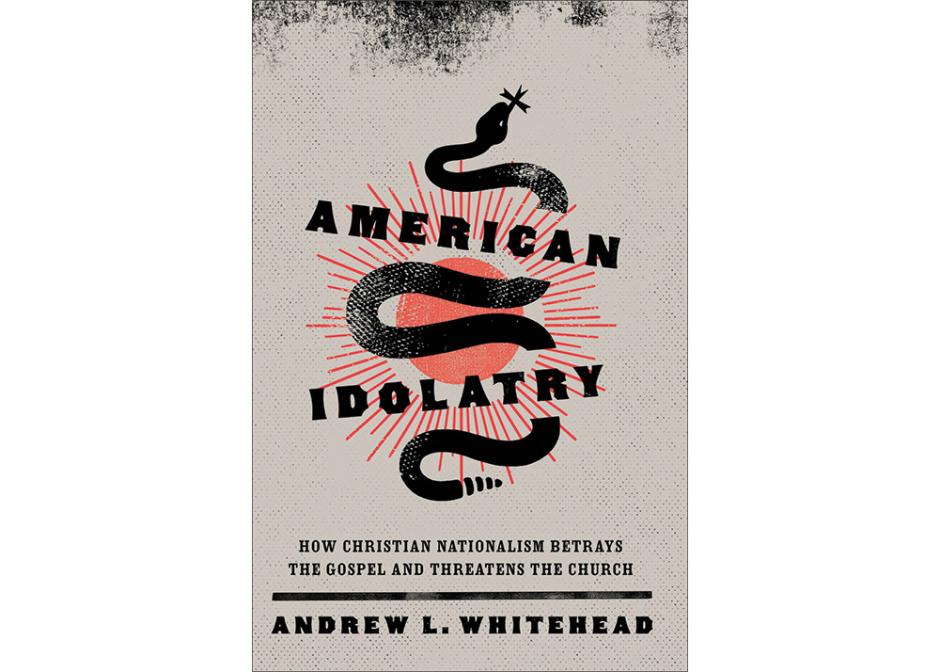

For a book written by a social scientist, Andrew Whitehead’s American Idolatry has surprisingly few statistics in the opening pages (American Idolatry: How Christian Nationalism Betrays the Gospel and the Church [Grand Rapids: Brazos Press, 2023]). Instead, Whitehead, a nationally known writer and speaker on religion in America, has a more personal story to share—a story of faith, discovery, and hope. His latest book explores the corrosive influence of religious nationalism within American Christianity, and it doesn’t always make for comfortable reading. Whitehead’s warm, relatable approach, however, helps this difficult topic feel less daunting.

Whitehead is an associate professor of sociology and director of the Association of Religion Data Archives at the Center for the Study of Religion and American Culture at Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis. His 2020 book, Taking America Back for God: Christian Nationalism in the United States, authored with Samuel Perry, won the 2021 Distinguished Book Award from the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion.

Bettina Krause, editor of Liberty magazine, recently spoke with Professor Whitehead about his motivation for wading, yet again, into the challenging and often divisive waters of White Christian nationalism.

Bettina Krause: Your last book, written with Sam Perry, gave us an in-depth look at the research and data around religious nationalism. But American Idolatry has a distinctly different tone. Why did you write this book?

Andrew Whitehead: I’m really trying to speak directly to a Christian audience. I’m a Christian, and I want to speak to those folks who, like me, grew up in largely White Christian spaces. I wanted to highlight the personal journey I’ve been on in my faith, and how that has intersected with my professional journey, studying religion in America and Christian nationalism.

For the most part, we social scientists don’t make normative claims—we’re just laying out evidence. But with this book I wanted to take that next step and say, “Hey, we claim we want to follow the way of Christ, but Christian nationalism just gets in the way. It hinders us from living our faith.”

Whenever we talk or write about Christian nationalism, I think it’s important to italicize the ism. We’re looking at Christian nationalism; we’re not trying to label folk as Christian nationalists. Christian nationalism is clearly on a spectrum. It’s not binary—something that someone either is or isn’t. People can embrace certain aspects of it strongly, and other aspects not as strongly.

So with this book I’m trying to thread that needle and say, “I’m not attacking anyone personally, but I do want us to look very closely at this belief system, this cultural framework, that we’ve been handed, and to question it.”

Krause: Your book focuses specifically on White Christian nationalism. You write that it’s important not to leave off this adjective when discussing Christian nationalism within the American context. Why?

Whitehead: I’d define Christian nationalism as a cultural framework that seeks to fuse American civic life with a particular expression of Christianity. But, of course, there are many different expressions of Christianity in America, so what are we talking about? It’s an expression that’s both ethnocentric and politically religiously conservative.

It’s important to call this White Christian nationalism because Christian nationalism, both historically and today, tends to benefit a particular group—White American natural-born citizens. It isn’t the skin color of a person who might embrace Christian nationalism that matters. I’m not talking about White Christian nationalism simply in terms of White people, but “Whiteness.” And Whiteness is made up of values, beliefs, behaviors, and attitudes that result in the organization of our society in such a way that it, by and large, benefits one group over others.

Krause: Your book is titled American Idolatry—what idols are you referring to here?

Whitehead: I focus on three really important idols, and the first is power. When we talk about White Christian nationalism in the United States, when we really get down to it, it’s absolutely focused on gaining privileged access to power. This is power in the sense of using it for self-interested ends to benefit only “us,” the people who are in the “in group.”

The second idol that I talk about is fear. And as we look through American history, but especially during the past 40 or 50 years with the rise of the Christian Right, fear has been used as a political tool to help draw lines of distinction between the “us” and the “them.”

For instance, in my book I talk about fear of immigrants and how they might raise the crime level in our communities. Well, let’s investigate this claim. And in doing so, social science is a powerful tool. When we look at the data, we find that there’s no evidence of increased crime in communities with higher levels of immigrants. In fact, some studies show lower levels of crime.

And then the last idol that I talk about in the book is violence. When Christian nationalism is focused on gaining privileged access to power for self-interested ends, and when it draws lines of distinction between “us” and “them” based on fear, then the natural outcome is violence. We can see, throughout our history, that violence—whether enacted or threatened—is the result of our efforts to defend access to power from those we’re supposed to fear.

Krause: One of the many practical sections of your book is your “field guide to Christian nationalism,” and it identifies certain red flags we may not otherwise notice. I wanted to focus on just one of those—the tradition of having an American flag displayed in church sanctuaries. I spent my early years in Australia, where I’d never seen flags in churches. So when I moved to America 25 years ago, this was jarring for me. Now I don’t notice it at all. Tell me why something as commonplace as a flag in a sanctuary is a warning sign.

Whitehead: I think your experience gets at an important point. In many ways American Christians have become blind to certain practices, and our Christian brothers and sisters from other countries can help us see our blind spots.

In our most recent data collection, where we asked congregations if they have flags in their sanctuary, around 60 percent of congregations said, “Yes, we have a national flag in our sanctuary space.”

That’s a lot of congregations. As I talk with pastors, they tell me that a sure way to anger half their congregation is to move the flag or take it out of the sanctuary. So my question becomes, “Why would people be angry if the flag gets moved? What does that tell us about what that flag stands for within our main worship space?”

As you shared, the American flag in a worship space represents something very different for our Christian brothers and sisters in Australia. It wouldn’t fit, because they’re not American. So why is the flag of just one nation in the sanctuary if Christianity is a global community that spans all nations and people groups? What purpose does it serve?

I certainly don’t want to demonize anyone who has a flag in their worship space, but I do want us to at least wrestle with it, and to think through the implications. Elevating one nation, implying that we’re in some way unique, or that God’s plan for the world in some ways depends upon the greatness of the United States—I think those are very dangerous assumptions.

Krause: One of my favorite metaphors in your book is related to how Christians can confront Christian nationalism in their own lives. You say that it’s not like performing an amputation—simply cutting off a limb. It’s more like flossing. Please explain.

Whitehead: I heard this metaphor used in relation to how we can respond to racism. It isn’t as though White Americans can simply say, “Oh, I am now free of any racist assumptions.” We can’t just “amputate” racism from our lives and society, and it’s done.

I think it’s the same for Christian nationalism. It isn’t that one day we see the light, and so now it’s all over. It’s more like flossing, where every day on our journey we need to faithfully take what seem like little steps. Flossing isn’t big, but if you don’t do it for months or even years, then our teeth can start to rot.

But consistent, faithful work can ensure that we’re moving forward and confronting Christian nationalism in small but important ways.

Krause: What are some of those little flossing actions you talk about?

Whitehead: Throughout the book I tried to provide examples of folk who are confronting Christian nationalism in their daily lives. When we talk about religious freedom, for instance, we should talk about religious freedom for everyone. We should say, “All people of all faiths or no faith at all have an equal right to fully participate in our democracy.”

Or it might be defending the right or access to vote. If there are movements in your county or state, or even nationally, that are trying to limit people’s access to voting, I think that, as Christians invested in the flourishing of all society, we could defend that right to vote.

A friend of mine runs a nonprofit that helps refugees who are relocated to her community. As she interacts with these groups, she’s able to see the barriers they face, such as being able to take a driver’s test in their own language. She found that the manual wasn’t offered in their language, so they couldn’t study for the test. So she partnered with them to make the manual available in their language and some other languages as well.

These are just small things, but the through line that connects them is this: we need to decenter ourselves and locate ourselves instead with different marginalized groups. We need to listen to these people and try to see the world from their perspective. Ask, “What’s creating hardships for them and preventing them from flourishing? How can I partner with them to help overcome that?”

Krause: You tell the story in your book of watching two students, many years ago, debating whether America’s invasion of Iraq was somehow sanctioned by God—an American student and an Australian student. And you say it was like watching two people talk about the same thing but using completely different dialects.

How optimistic are you that Christians are going to learn to speak the same “language” when it comes to Christian nationalism?

Whitehead: It’s a fair question, and to be honest, my level of optimism probably depends on the day, or even the time of day. But as a Christian I have to practice hope. If there’s no hope, then the forces of evil and oppression have won. I do have hope, and I believe we can make a difference for the future.

We can be very patriotic. We can love our country and be proud of our country’s achievements. But at the same time, we can also refuse to shy away from uncomfortable questions, such as “Well, how did that wealth get built?” It didn’t just happen. We can be real about that, and then we can be prepared to do the reparative work going forward. That’s what I hope to be a part of.

Article Author: Bettina Krause

Bettina Krause is the editor of Liberty magazine.