Clause and Effect

Martin Surridge March/April 2014he history of how the nation’s Founders empowered American religious freedom has been well documented over centuries of legal arguments, court proceedings, public discussions, and historical analyses. Lectures on the importance of Jefferson’s letter to the Danbury Baptists, or the significance of the First Amendment’s establishment and free exercise clauses are commonplace enough today, while it is taken for granted that both the federal and state governments grant far-reaching, unconquerable religious freedoms.

However, the story of one particular piece of legal framework, the nation’s first constitutional protection regarding religious freedom, prior even to that of the Bill of Rights, has had a much greater impact and a more fascinating history than many might realize.

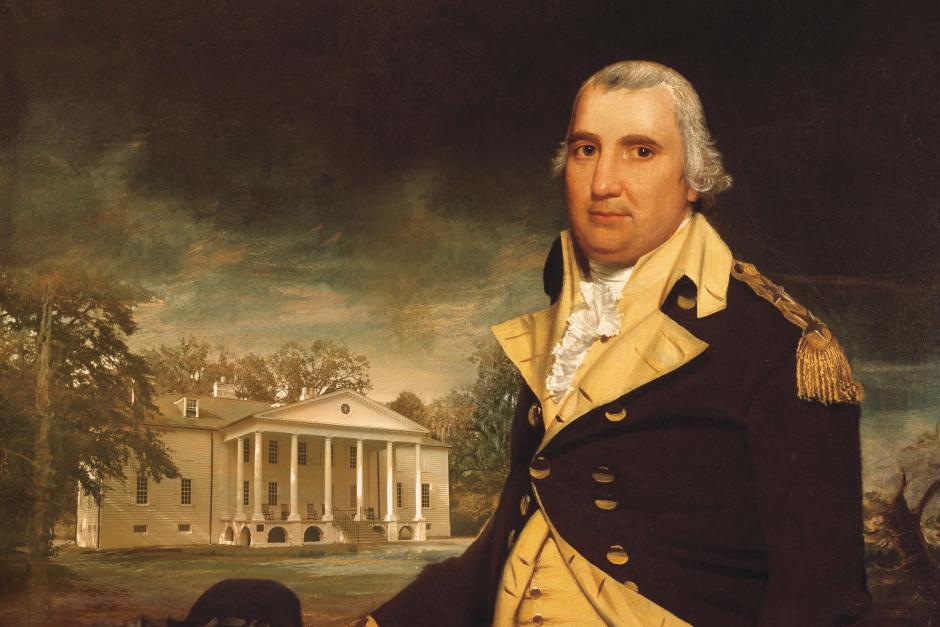

Tucked away within Article VI of the United States Constitution is a vital clause, the importance of which has become nearly as forgotten as the unheralded Founder who included it in the document and introduced it to the world more than 225 years ago. Without the addition of the “no religious test” clause, introduced by Charles Pinckney of South Carolina, the nature of the United States government and very essence of American life could have been profoundly different.

Pinckney, a lieutenant in the Revolutionary War, was captured by the British and held as a prisoner of war before eventually making a name for himself as a senator, a congressman, and the governor of South Carolina. He remains one of our least known Founders, and his defining moment may be even less well known. Even though Pinckney’s constitutional contribution of the “no religious test” clause is almost certainly his most important accomplishment, many biographical sketches of him—including those on South Carolina’s Information Highway Web site, the U.S. Army Web site, and the Biographical Directory of Congress Web site3 —fail to mention this fact.

For those of us yet to commit the Constitution to memory, the third paragraph of the sixth article is as follows:

“The Senators and Representatives before mentioned, and the members of the several state legislatures, and all executive and judicial officers, both of the United States and of the several states, shall be bound by oath or affirmation, to support this Constitution;”—so far so good, but it was the following 21 words that changed the course of world events and set the United States apart from every other civilization in human history—“but no religious test shall ever be required as a qualification to any office or public trust under the United States.”4

Until the ratification of the United States Constitution, and the implementation of a brand-new system of republican rule that it created, every form of government around the world, those that existed at time of ratification and even those during the thousands of years before, all required leaders to belong to a particular religious belief system. Heads of state and government, dating from colonial Britain and Spain all the way back to Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, had always adhered to a specific state-ordained faith. From the highest echelons of power, religious intolerance could flow down freely with such a dynamic. But the historical current was about to be reversed.

Charles C. Haynes, director of the Religious Freedom Education Project at the Newseum and a senior scholar at the First Amendment Center, explained the significance of this moment in a piece written for Civitas: A Framework for Civic Education.

“At the time of the Constitutional Convention in 1787,” Haynes wrote, “most of the colonies still had religious establishments or religious tests for office. It was unimaginable to many Americans that non-Protestants—Catholics, Jews, atheists, and others—could be trusted with public office. . . . Remarkably, the ‘no religious test’ provision passed with little dissent. For the first time in history, a nation had formally abolished one of the most powerful tools of the state for oppressing religious minorities.”5

This clause would prohibit formal litmus tests of religion from being applied to candidates for federal office, yet its scope was not applied to state governments until later. During the centuries that followed, the presence of the clause within Article IV would give the courts the legal authority to abolish religious tests in every state, with judicial decisions made during “1868 in North Carolina, 1946 in New Hampshire, and 1961 in Maryland. . . . Maryland had required since 1867 ‘a declaration of belief in God’ for all officeholders. When the U.S. Supreme Court struck down this requirement in its 1961 decision in Torcaso v. Watkins, freedom of conscience was fully extended to include nonbelievers as well as believers.”6

Was Charles Pinckney, a planter and lawyer from Charleston, truly attempting to undo millennia of discrimination and usher in a new age of freedom? Maybe not, especially given that Pinckney’s other notable contribution to constitutional liberty was the inclusion of the notorious fugitive-slave clause in Article IV. So, what was his motivation? Rob Boston, director of Communications at Americans United for Separation of Church and State, wrote in Church and State magazine that Pinckney’s passion for religious liberty “might [have derived from] something as simple as his study of America’s then-foe, Great Britain. During one speech, he blasted the British system of state-established religion for disenfranchising millions.

“Pinckney was also a strong supporter of Thomas Jefferson,” Boston wrote, “and might have been influenced by the Virginian’s strong pro-religious freedom bent.”7

Boston also cited church-state scholar Anson Phelps Stokes, who asserted in his 1950 three-volume Church and State in the United States that “during the Constitutional Convention, Pinckney showed more interest in religious liberty than any member except Madison.”

However, the Library of Congress has also pointed out that a likely reason for the inclusion of the religious test clause was simply “to defuse controversy by disarming potential critics who might claim religious discrimination in eligibility for public office.”8

Whether or not Pinckney was so selfish as to include a constitutional clause that would silence his opposition in future political fights is uncertain. However, let us not forget that this was a politician and plantation owner that, while debating the merits of the privileges and immunities clause in Philadelphia, commented that “some provision should be included in favor of property of slaves,” and moved “to require fugitive slaves and servants to be delivered up like criminals.”9 He also threatened to withdraw South Carolina from the convention if slavery was formally addressed in any way at all. Pinckney’s strong defense of slavery was unsurprising given that he was a member of the Deep South gentry and a plantation owner where 40 men, women, and children were enslaved.10 Pinckney’s support of slavery went so far as to see him protest the Missouri Compromise after he was elected to the House of Representatives almost 30 years after ratification.11

Such deep and long-lasting resistance to even the most partial abolitionist efforts may seem unusual for such a champion of constitutional freedoms, but this paradoxical nature would also have been present in other Southern Founders, including George Washington and Thomas Jefferson.

Such was the contradictory life of Charles Pinckney. A National Park Service inventory of Pinckney’s Snee Farm plantation, from 1787, the very same year as the Constitutional Convention, can afford us a glimpse into the lives of slaves who would never know the meaning of Pinckney’s contributions to freedom. While the 29-year-old delegate to the Constitutional Convention remained stubbornly undeterred by the initial efforts to ignore adoption of his no religious test clause, Cyrus—an enslaved carpenter, who was Pinckney’s most expensive acquisition—would have been carving and cutting wood back in South Carolina, fully aware of the power of his master’s stubbornness. As Pinckney continued his political maneuverings, once again introducing the proposal on the full floor, Jack the field slave would likewise have been repeating his own tasks in his master’s rice and indigo fields, again and again. And when Pinckney’s proposal was seconded by Gouverneur Morris and adopted by the other delegates, expanding the reaches of American legal freedom from that point forward, enslaved shoemaker Congaree Ned would have been able to look toward the fence line knowing exactly which post constrained the limits of his freedom.

From its inception onward, the no religious test clause has been fraught with contradictions. Even if one were to overlook the hypocrisy and double standards of Pinckney himself, there is the small matter of how six states still have language in their constitutions requiring a belief in God in order to take public office. Arkansas, Mississippi, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, and Texas have provisions that have yet to be singled out and struck down by federal courts, whereas those of Maryland and Pinckney’s home state of South Carolina were specifically overruled. While these unenforced laws may only remain on state books and contradict the federal government merely in a symbolic way, it is the pro-religious nature of American attitudes toward political candidates that poses the most significant problem. Public opinion demonstrates how despite the presence of the no religious test clause, most voters take religion into account when deciding who to support on Election Day.

When former U.S. Representative Barney Frank (D-Mass.) casually and humorously admitted that he was an atheist on Real Time With Bill Maher back in August, the news was that the 16-term retired congressman had divulged yet another personal secret, and had waited until after he was out of office when voters couldn’t hold his lack of religion against him. Frank had come out as gay in 1987 and served openly while in Congress, but had waited until his retirement to admit his atheism. Covering the story for Politico Magazine, Jennifer Michael Hecht, in an article titled “The Last Taboo,” pondered the question “Was it really harder to come out as an atheist politician in 2013 than as a gay one 25 years ago?”12

Hecht believes that it is more difficult, and she strengthened her argument by pointing to the total absence of self-described atheists in Congress, in addition to a recent Gallup poll that “found (once again) that atheists are the least electable among several underrepresented groups. Sixty-eight percent would vote for a well-qualified gay or lesbian candidate, for example, but only 54 percent would vote for a well-qualified atheist”—and Muslims did not fare much better, polling at only 58 percent.14 Hecht argues that since approximately “6 percent of Americans say they don’t believe in a higher power”, according to a 2012 Pew Report, “at least 15 million Americans are without any elected officials to represent their point of view” and that “atheism is still as close as it gets to political poison in American electoral politics.”

Rob Boston lamented the contradiction of the no religious test clause, writing that “today, Pinckney barely rates a mention among the founding fathers. And, sadly, many Americans don’t appreciate his handiwork. In fact, Americans seem to have imposed a de facto religious test for public office. Voters seem most comfortable with candidates who embrace a faith that is considered part of the mainstream.”15

“Thus, we find ourselves in a curious situation,” Boston continued. “The Constitution mandates no religious test for public office, yet much of the voting public seems to want one that says that at the very least, a candidate must believe in God and be willing to incorporate religious rhetoric in public pronouncements.”

Pinckney and his fellow Founders were right to fear the idea of the religious test; what they didn’t know was that the questions on the test wouldn’t be asked by the judges of the United States, but by its pollsters.

- www.sciway.net/hist/governors/cpinckney.html.

- www.history.army.mil/books/RevWar/ss/pinckneyc.htm.

- bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=P000354.

- United States Constitution Article VI.

- Charles C. Haynes, “History of Religious Liberty in America”, inCivitas: A Framework for Civic Education. (Council for the Advancement of Citizenship and the Center for Civic Education, 1991); Available online at www.firstamendmentcenter.org/history-of-religious-liberty-in-america.

- Haynes, “History of Religious Liberty in America”, inCivitas: A Framework for Civic Education; available online at www.firstamendmentcenter.org/history-of-religious-liberty-in-america.

- Rob Boston, “Pinckney’s Promise: ‘No Religious Test’ for Public Office in America!”, in Church and State, June 2011; available online at www.au.org/church-state/june-2011-church-state/featured/pinckney%E2%80%99s-promise.

- “Religion and the Founding of the American Republic”, Library of Congress; available online at www.loc.gov/exhibits/religion/rel06.html.

- Matthew Spalding, ”Fugitive Slave Clause,” The Heritage Guide to the Constitution, www.heritage.org/constitution/#!/articles/4/essays/124/fugitive-slave-clause.

- “African Americans at Snee Farm,” National Park Service, Charles Pinckney National Historic Site; available online at www.nps.gov/chpi/planyourvisit/upload/African_Americans_at_Snee_Farm.pdf.

- United States Archives, “Charles Pinckney”; available online at www.archives.gov/exhibits/charters/constitution_founding_fathers_south_carolina.html#Pinckney.

- Jennifer Michael Hecht, “The Last Taboo,” Politico Magazine, December 09, 2013; available online at www.politico.com/magazine/story/2013/12/the-last-taboo-atheists-politicians-100901.html.

- www.gallup.com/poll/155285/atheists-muslims-bias-presidential-candidates.aspx.

- Hecht, “The Last Taboo.” Politico Magazine; www.politico.com/magazine/story/2013/12/the-last-taboo-atheists-politicians-100901.html.

- Boston, “Pinckney’s Promise: ‘No Religious Test’ for Public Office in America!” Church and State, June 2011; available online at www.au.org/church-state/june-2011-church-state/featured/pinckney’s-promise.

Article Author: Martin Surridge

Martin Surridge has a background in teaching English. He is an associate editor of ReligiousLiberty.TV, an independent news Web site. He writes from Calhoun, Georgia.