Coexistent Rights

Alan E. Brownstein May/June 2009

On November 4, 2008, California voters approved Proposition 8, a state constitutional amendment prohibiting same-sex couples from marrying. The proponents of Proposition 8 based several of their arguments supporting this amendment on the premise that same-sex marriages posed a threat to religious liberty. Many of these arguments were exaggerated and disproportionate to any real conflicts that may arise between laws recognizing same-sex marriages and religious freedom. Indeed, as I hope to demonstrate in this article, the basic premise of their argument—that the right of same-sex couples to marry and the liberty of religious individuals and institutions cannot coexist together—may be misguided and could turn out to be counterproductive.

Certainly many religious people believe that homosexual relationships violate the tenets of their faith and are concerned that a decision by the state to permit same-sex couples to marry legitimates conduct that they believe to be immoral. There is no doubt that our society is divided on this moral issue. But this moral debate is distinct in important respects from the legal question of whether same-sex couples should have the right to marry. We typically do not conflate the state permitting the exercise of a right with the state’s (or the majority’s) approval of the way the right is exercised. Freedom of speech, for example, protects the right to express messages that many people consider immoral, and it protects the right of those who are offended by such speech to criticize and challenge its expression. Similarly, state recognition of the right of same-sex couples to marry does not suggest that everyone in our society acknowledges the moral propriety of such relationships, and, more important, it does not interfere with the religious liberty of those who challenge the morality of same-sex relationships as a matter of faith.

The claimed conflicts

The proponents of Proposition 8 made two primary arguments during their campaign. First, they said if Proposition 8 was not passed, churches would be required to marry same-sex couples and would lose their tax-exempt status if they did not do so. 1 . Second, they argued that without Proposition 8, schools would be required to teach young children about same-sex marriage, even over parental objections.2

The first claim—that churches will lose their tax exempt status if their clergy refuse to solemnize the weddings of same-sex couples—is simply false. The California Supreme Court explicitly noted in the Marriage Cases that “no religious officiant will be required to solemnize a marriage in contravention of his or her religious beliefs.” 3 No evidence exists that churches have been subject to legal sanction for refusing to marry same-sex couples, interfaith couples, previously divorced couples, or anyone else for that matter. The First Amendment clearly prohibits government from regulating religious ceremonies. 4

The second claim—that children in public school will be taught about same-sex marriage even though their parents object to such instruction—ignores the California Code section providing a right to opt out of objectionable lessons related to sexual health education.5 But that isn’t its major failing.

Religious parents are often concerned about material taught in public schools today. Some parents object to lessons discussing heterosexual conduct and contraception, for example. Equally intense conflicts arise when public schools teach about religion or celebrate religious holidays.

All of these disputes raise important and difficult questions. But the same-sex marriage issue is the only one in which advocates assert the kind of disproportionate response presented by Proposition 8 supporters—that to avoid the possibility of a controversial discussion in a classroom, we should amend the Constitution to ensure that a group of adults cannot exercise the right to marry. No one would think it was reasonable or fair to contend that a dispute about teaching birth control to students justifies banning adults from obtaining access to contraceptives. Similarly, if some teachers improperly teach religion in their classes or take students to a religious service during a field trip, no one would argue that the appropriate response is to prohibit religious services by the faith in question. Put simply, it just doesn’t make sense to argue that the state should limit the rights of adults as a way of controlling the lessons taught to children in school.

The use of exaggerated and disproportionate arguments to support Proposition 8 is no small matter. Because there is no objective way to define or measure religious belief and commitment, religious liberty, more than any other right, depends on the credibility of its advocates. As anyone who has lobbied and argued for religious liberty legislation and policies knows, we are often challenged by arguments about sham claims and manufactured beliefs. Thus, religious liberty advocates must be credible and their arguments must be accurate. The campaign for, and passage of, Proposition 8 will be a Pyrrhic victory for religious liberty at best if, as I fear, it convinced many Californians that claims about religious liberty cannot be trusted.

It is not necessary to prohibit same-sex couples from marrying to protect religious liberty.

In the great majority of situations, the state recognizing same-sex “marriages” will not burden religious liberty in any way. But on some occasions conflicts will arise. In other contexts in which conflicts arise between religious liberty and important interests and public policies, we use appropriately limited legal tools, such as religious accommodations and exemptions, to resolve the problem.

Protesters against Proposition 8 demonstrate in front of the California State Capitol in Sacramento.

In thinking about such situations, it is important to remember that all antidiscrimination laws create some risk of conflict with religious freedom. Laws prohibiting gender-based and religious discrimination in hiring risked serious interference with the autonomy of many religious institutions and employers. These concerns did not prevent our society from prohibiting religious and gender-based employment discrimination, however. Nor do similar concerns justify prohibiting a large class of individuals from marrying the persons with whom they want to share their lives. There is no basis for rejecting a public policy that may result in occasional burdens on religious liberty when carefully drafted accommodations can be employed to reconcile those conflicts that do arise.

Some may argue that I understate the danger to religious liberty. The model used for recognizing same-sex marriages, they say, has been racial equality. Gays and lesbians have been analogized to African-Americans. This means that protecting same-sex marriages against discrimination will constitute a sufficiently compelling state interest to justify intruding into the autonomy of religious institutions. The controlling case here is Bob Jones University v. United States.6 If a fundamentalist religious college can lose its tax-exempt status because it denies admission to participants in an interracial marriage and prohibits interracial dating, religious institutions that adopt similar rules relating to same-sex relationships may be similarly sanctioned.

This argument is unpersuasive. First, we need to understand the cultural foundation on which the Bob Jones decision is based. Bob Jones University was an extraordinary outlier in its beliefs. By 1983 virtually every religious denomination of any size in the United States rejected racism as a religious tenet. Without that kind of normative consensus among religious faiths, the decision in Bob Jones would have been untenable. No similar religious consensus exists with regard to sexual orientation.

Second, sexual orientation is not race. Nothing is. Race discrimination is the quintessential evil that has plagued American history. No other antidiscrimination interest carries with it the force of eradicating racial discrimination from our society. The goal of prohibiting gender discrimination, for example, carries far less weight. Gender exclusive private colleges are not treated the same way as racially exclusive schools. Thus, the likelihood that race and sexual orientation discrimination cases will always parallel each other seems speculative at best.

Third, there is a much more accurate analogy for dealing with discrimination based on sexual orientation than race discrimination. For liberty and equality purposes, gays and lesbians are not like African-Americans. Liberty and equality rights based on sexual orientation share common foundations with rights based on religious identity and belief. Like religion, a person’s sexual orientation is a core aspect of his or her identity.

In fact, analogizing the right of same-sex couples to marry to religious liberty and equality rights resolves many of the supposed “threats” to religious liberty alleged by Proposition 8 proponents. Our commitment to religious liberty and equality has never been understood to interfere with a religious institution’s decisions to reserve its spiritual activities for those individuals who adhere to the tenets of its faith. That principle should protect a church’s decision not to honor or solemnize same-sex marriages as well.

Arguments can be counterproductive for the cause of religious liberty.

Not only does same-sex marriage present much less of a threat to religious liberty than Proposition 8 proponents claimed, but arguments asserted in opposition to same-sex marriage actually undermine many of the foundations on which religious liberty is based.

One of the primary grounds for opposing same-sex marriage is the argument that there is no history or tradition recognizing such marriages. This position—that Western traditions determine the scope of fundamental rights—has been rejected by people of faith committed to religious liberty, and for good reason. Free exercise rights would be unreasonably narrowed under this model. Traditionally, Jews, other religious minorities, and indigenous peoples have received little respect for their religious beliefs and practices.

Another argument against recognizing same-sex marriages insists that there is a religious dimension and a sacred quality to the institution of marriage—and that it is unacceptable for government to permit same-sex couples to marry when God reserves marriage for a man and a woman. But if religious liberty and equality mean anything, it is that the theological understanding of majority faiths as to what is sinful and sacrilegious cannot be imposed by government on minorities. We cross an important line when we contend that some faith communities’ understanding of the sacred nature of marriage should be enforced by government.

Religious liberty and equality is predicated on the right to be different. Its underlying principle is that we do not have to accept the truth or value of someone else’s religious beliefs in order to agree that those beliefs and practices deserve protection against discriminatory treatment. Followers of faiths we consider to be false may be sinners in our eyes, but we still protect their right to be free from government coercion and discrimination. For example, the Ten Commandments state that “You shall have no other gods before Me.” Yet the Constitution and religious liberty statutes clearly protect religions that violate this commandment. Doing so neither undermines the meaning of the Ten Commandments nor expresses government approval of nonmonotheistic faiths. It simply recognizes the importance of religious autonomy to human dignity and personal liberty.

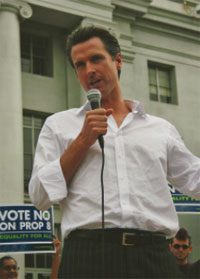

san francisco mayor gavin newsom speaks at an anti-Proposition 8 rally.

The willingness of opponents of same-sex marriage to accept the disparagement of same-sex couples by assigning them the subordinate status of civil unions also clashes with basic religious liberty and equality principles. Even when there is no material discrimi¬nation among religions, we don’t dismiss the dispar¬agement of minority faiths. Thus, for example, if the government declared that from now on Judaism and the Seventh-day Adventist faith would be classified as “belief systems” rather than religions, but they would still receive the same legal protections provided to recognized faiths, I doubt that I or many readers of this magazine would find that declaration acceptable. Similarly, even if the government protects the free exercise rights of non-Christians, it cannot declare

the United States to be a Christian nation. Yet opponents of same-sex marriage minimize the stigmatic consequences of the government imposing a badge of inferiority on gays and lesbians by restricting their relationships to civil unions.

What is most tragic about Proposition 8 is that it will make it even harder for people to understand that instead of being seen as inconsistent values, religious liberty and gay and lesbian rights should be understood to reinforce each other. Both religious individuals and gays and lesbians seek personal autonomy. They want to be able to live their lives based on who they are—not on someone else’s idea of who they should be. The best way to resolve conflicts between the right of same-sex couples to marry and free exercise rights is for advocates from both sides to recognize the basic truth that the best way to persuade someone to respect your rights is to demonstrate that you are willing to respect their rights.

- Laurie Goodstein, “A Line in the Sand for Same-Sex Marriage Foes,” New York Times, Oct. 27, 2008, A12 (noting that “in television advertisements, rallies, highway billboards, sermons and phone banks, supporters of Proposition 8 are warning that if it does not pass, churches that refuse to marry same-sex couples will be sued and lose their tax-exempt status”).

- Jessica Garrison, “A Prop 8 Fight Over Schools; Gay Marriage Will Be Taught if Item Fails, Say Backers,” Los Angeles Times, Oct. 19, 2008, B1.

- 183 P. 2d. 384, 451-452 (2008).

- 59 constitutional law professors from 14 California law schools signed a statement affirming that the First Amendment “protects a religion’s decisions about whether to solemnize or recognize particular marriages.” Michael Gardner, “Law Professors Enter Prop 8. Fray on Church’s Tax-Exempt Status,” San Diego Union-Tribune, Oct. 30, 2008, A3.

- California Education Code Section 51240.

- 461 U.S. 574 (1983).

Article Author: Alan E. Brownstein

Alan E. Brownstein, a nationally recognized Constitutional Law scholar, teaches Constitutional Law, Law and Religion, and Torts at UC Davis School of Law. While the primary focus of his scholarship relates to church-state issues and free exercise and establishment clause doctrine, he has also written extensively on freedom of speech, privacy and autonomy rights, and other constitutional law subjects. His articles have been published in numerous academic journals, including the Stanford Law Review, Cornell Law Review,UCLA Law Review and ConstitutionalCommentary. In 2008, Liberty was privileged to recognize Professor Brownstein for his passion and dedication to religious freedom at its annual Religious Liberty Dinner in Washington, D.C.