Cross Purposes

Matthew F. McMearty March/April 2010

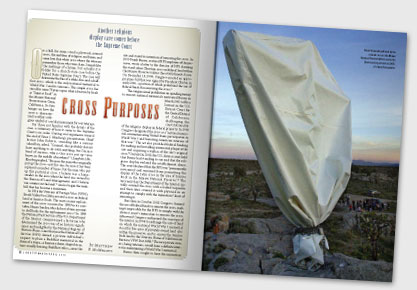

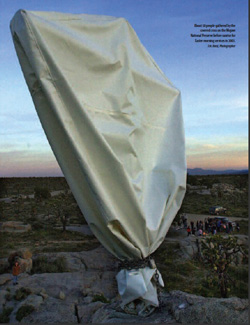

In a hill, far away, stood a plywood-covered cross, the emblem of religion and fame; and some love that white cross where the veterans remember those who were slain. Sounds like the makings of a hymn, but actually it is fodder for a church-state case before the United States Supreme Court. The case will determine the fate of a white, five-and-a-half-foot cross, which is the only national memorial to World War I and its veterans. The simple cross has stood for some 75 years upon what is known by locals as “Sunrise Rock” in the Mojave National Preserve near Cima, California. Its fate hinges on how the cross is characterized: as either a religious symbol or a secular monument for war veterans.

For those not familiar with the details of the case, a summary of how it came to the Supreme Court is in order. During oral arguments toward the end of Peter J. Eliasberg’s presentation, Chief Justice John Roberts, sounding like a curious schoolboy, asked, “Counsel, this probably doesn’t have anything to do with anything, but I’m just kind of curious, why is this cross put up—you know, in the middle of nowhere?” (Laughter.) Mr. Eliasberg replied, “Because the man who originally put up the cross—not this one, because it has been replaced a number of times, but the man who put up this particular cross, I believe was a homesteader in the area when the land was owned by the Bureau of Land Management, and I believe was a miner on the land.”1 And so began the molehill that has become a mountain.

In 1934 the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW), Death Valley Post 2884, erected a cross on federal land at Sunrise Rock. The most recent replacement of the cross occurred in 1998 by its caretaker, Henry Sandoz, who did not obtain a permit to drill holes for the replacement cross.2 In 1999 the National Park Service of the U.S. Department of the Interior commissioned a historian who determined the cross was of no historic significance and ineligible for the National Register of Historic Places. Later that year the National Park Service (NPS) denied a private individual’s request to place a Buddhist memorial in the form of a stupa—a funerary dome-shaped structure usually housing Buddhist relics—near the site and stated its intention of removing the cross. In 2000 Frank Buono, a retired NPS employee of the preserve, wrote a letter to the director of NPS claiming the stand-alone Christian cross on federal land within the Mojave Preserve violates the establishment clause. On December 15, 2000, Congress enacted an appropriations bill that was signed by President Clinton in early 2001, a portion of which prohibited the use of federal funds for removing the cross.3

The congressional prohibition on spending money to remove national memorials motivated Buono in March 2001 to file a lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California, challenging the constitutionality of the religious display on federal property. In 2002 Congress designated the cross as a “national memorial commemorating United States participation in World War I and honoring American veterans of that war.” The act also provided federal funding for making and installing a memorial plaque at the site and acquiring a replica of the site’s original cross.4 On July 24, 2002, the U.S. district court held that Buono had standing to sue and that the religious display violated the establishment clause. The court declared that the NPS was “permanently restrained and enjoined from permitting the display of the Latin cross in the area of Sunrise Rock in the Mojave National Preserve.”5 The very next day, the Department of the Interior initially covered the cross with a locked tarpaulin and then later covered it with plywood in an attempt to comply with the injunction,6 short of removing it.

But then in October 2002 Congress banned the use of federal funds to remove the cross, making it impossible for the NPS to comply with the district court’s injunction to remove the cross. Afterward Congress authorized the secretary of the interior in 2004 to exchange the acre of land on which the national World War I memorial stood for five acres of privately owned land also within the preserve, and to convey the Sunrise Rock land to the Veterans Home of California in Barstow, VFW Post 385E.7 The new private owners, being veterans, would have a definite interest in maintaining a World War I memorial. \

Buono then sought to have the injunction enforced. On June 7, 2004, a panel of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the district court’s holdings on Buono’s standing, establishment clause violation, and its injunction. Since the land transfer could take up to two years to complete, the panel also held that the land transfer did not moot the case and left “for another day” the issue of “whether a transfer . . . would pass constitutional muster.8 Consequently, in April 2005 the district court on remand addressed the constitutionality of the land transfer, asserting that “for this court, that day is today.” It held the land transfer unconstitutional and ordered that the secretary of the interior’s “agents, employees, successors, assignees, or anyone acting in concert with them are permanently enjoined from implementing the provisions” for a land transfer.9 The petitioners appealed. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in September 2007 affirmed the district court’s ruling, and then in May 2008, it denied the petitioners’ request for rehearing and en banc review.10 The petitioners appealed to the Supreme Court, which in February 2009 granted certiorari for the petitioners.11

This squabble over a small white cross out in the middle of no-man’s-land involves much more than who gets to determine how establishment clause violations get remedied. But before sinking deeper into the cold waters of technical judicial procedures that lie under the surface of this ice cube made into an iceberg, a biblical analogy will help to crystallize the issue of authority at stake in this church-state problem heightened by a legislative-judiciary dispute.

The Bible gives historical details from the period of Israel’s judges, and the overlap of that period overlapped with the beginning of the era of the kings. The Bible records in 1 Samuel 15 the story of what on the surface seemed a trivial dispute over whether or not some things under the divine ban were completely destroyed. Deep down, what was at stake was whether the word of the Lord spoken to Saul by the prophet Samuel was carried out by Saul as the Lord had commanded. Israel’s constitutional authority was its maker—Yahweh and His Ten Commandments. The prophetic office served as the judiciary, issuing clarifications of the divine will/word. It issued commands to ensure the divine will was carried out. King Saul was the executive branch, implementing the divine commands.

The Lord declared through Samuel, “Now go and strike Amalek and utterly destroy all that he has, and do not spare him” (1 Samuel 15:3).* This is a bit too much for our modern ears, but nevertheless, after Saul defeated the Amalekites, he “and the people spared [King] Agag and the best of the sheep, the oxen, the fatlings, the lambs, and all that was good, and were not willing to destroy them utterly; but everything despised and worthless, that they utterly destroyed” (verse 9).

After the Lord told Samuel that Saul “turned back from following Me and has not carried out My commands” (verse 11), Samuel later met and confronted Saul. Saul greeted Samuel and declared unabashedly, “Blessed are you of the Lord! I have carried out the command of the Lord” (verse 13). To which Samuel retorted, “What then is this bleating of the sheep in my ears, and the lowing of the oxen which I hear?” (verse 14). After declaring the “hearing” test, Samuel questioned Saul: “Why then did you not obey the voice of the Lord ?” (verse 19). To which Saul defiantly asserted, “I did obey the voice of the Lord, and went on the mission on which the Lord sent me, and have brought back Agag the king of Amalek, and have utterly destroyed the Amalekites” (verse 20).

To justify his course, Saul gave his rationalization for carrying out, in part, the Lord’s command to destroy everything: they spared the best for the purpose of eventually destroying the banned items when they would be sacrificed to the Lord (verses 20, 21). By focusing on sparing the sacrificial items, Saul had overlooked the fact that King Agag and the other secular items of the spoils were preserved contrary to Samuel’s judiciary injunction to remove all of the Amalekites and their possessions from existence.

Like two ships passing in the night, so went the dialogue between the two briefs presented to the Supreme Court in Salazar v. Buono prior to oral arguments heard by the Court on October 7, 2009. On behalf of the petitioners, Department of Justice solicitor general Elena Kagan argued that the actions of Congress merely attempted to preserve a national monument on behalf of war veterans while remedying—at least eventually—the violation of the establishment clause and by complying with the court’s injunction not to display the cross by covering it over with plywood.12 On behalf of Frank Buono the respondent, Peter J. Eliasberg, lawyer for the American Civil Liberties Union Foundation of Southern California, argued that all of Congress’s actions revealed a consistent pattern designed to preserve a Christian cross as a religious symbol in the same location in order to circumvent a district court’s injunction to remove it, while claiming—erroneously at least—Congress remedied the violation of the establishment clause by engineering a land transfer contrary to standard process. There is just one problem: the lower courts and the Supreme Court continue to hear the “bleating of the sheep” in their ears because the cross still stands while the court’s injunction in terms of ordering the removal of the cross is under dispute.

The lower courts held that the stand-alone religious symbol on federal property violated the establishment clause, and therefore, must be removed by the NPS. Congress’s actions are similar to the teenager being told by his parents to immediately clean up his room by putting everything away. He proceeds to do so over the next six hours by throwing his messy “stuff” into the closet and under the bed. Congress basically argued, like King Saul, that there are different ways of complying with the injunction to no longer “display” the cross and for “cleaning up” establishment clause violations. It just takes extra time to comply.13 Besides, the establishment clause does not dictate “how” its violation needs to be remedied, and Congress’s right to interpret the Constitution does not make it subject to the district court’s discretion.

The church-state establishment clause controversy is the tip of the iceberg, but that issue will not be the basis of the Court’s decision, at least if Justice Antonin Scalia’s view that crosses as war memorials are only secular symbols of the dead falls short of majority support.14 The basis of the decision will most likely turn on procedural matters. It would seem that a majority of the Court would have little difficulty with the legitimacy of Buono’s standing or right to bring a lawsuit. If they revisit Buono’s right to sue, then the case will end up like Hein v. Freedom From Religion Foundation, resulting in Salazar becoming a repetitive waste of the Court’s time and wisdom.15 Justice Stephen Breyer voiced his concern that from a procedural perspective, the case “is a little boring,” and questioned why the Court even heard the case.16

Will the Court uphold the lower courts and stop the congressional “wife swap” land transfer, resulting in the NPS destroying the cross just as the prophet Samuel destroyed Agag and the sacrificial livestock? That depends on how the Court clarifies whether or not the congressional land transfer legislation modified the lower court’s injunction to remove the cross. Of course, such procedural geek posturing hinges on whether or not the Court’s Conservative majority, a priori, wants the cross to remain.

On the one hand, one thing is certain: if the land transfer is overruled, the cross will be removed. But that will mean destroying an emotionally invested symbol of those who gave their lives in battle. It also will determine that Christian symbols united with ostensibly secular legislative purposes, per Smith, are uniting church and state. On the other hand, another thing is equally certain: if the land becomes private land, then the cross remains. That holding will mean Congress retains its own authority to interpret the Constitution to which the Supreme Court in principle acquiesces to the petitioners’ claim that lower courts cannot limit congressional authority to choose its own remedy for establishment clause violations. It also would mean the lower court’s permanent injunction amounted merely to a temporary “cover-up,” so to speak, until the land and the cross end up as private property. If the latter is the outcome, it only goes to prove, you can’t get around what the Lord means and what He says, but Congress might get around what a lower court says and means.

* Bible texts in this article are from the New American Standard Bible, copyright ©1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995, by The Lockman Foundation. Used by permission.

- Ken Salazar, Secretary of the Interior, et al., v. Frank Buono, oral arguments, Peter J. Eliasberg, Esq., on behalf of the respondent, p. 54. (www.supremecourtus.gov/oral_arguments/argument_transcripts/08-472.pdf. Accessed November 30, 2009.) Hereafter, Salazar v. Buono, oral arguments.

- Buono v. Kempthorne, 527 F.3d 758 (9th Cir. 2008), 11798-11799.

- 2001 Act App. D, § 133, 114 Stat. 2763A-230.

- 2002 Act § 8137(a-c), 115 Stat. 2278. The amount of funding was up to $10,000 from the NPS budget.

- Buono v. Norton, 212 F. Supp. 2d 1202, 1217 (C.D. Cal. 2002).

- Buono v. Norton, 364 F. Supp. 2d 1175 (C.D. Cal. 2005).

- Department of Defense Appropriations Act 2004 § 8121(a), (b), 117 Stat. 1100: see also, Pub. L. No. 108-187, 117 Stat. 1054 (2003).

- Buono v. Norton, 371 F.3d 543 (9th Cir. 2004), at 550.

- Buono v. Norton, 364 F. Supp. Ed 1175 (C.D. Cal. 2005).

- Buono v. Kempthorne, 527 F.3d 758 (9th Cir. 2008).

- Salazar v. Kempthorne, 129 S. Ct. 1313 (U.S. 2009).

- This argument’s approach on the one hand denies the cross is a religious symbol because Congress is trying to preserve a secular war memorial, while on the other, Congress by its actions acknowledges it is a religious symbol per the courts’ perspective that it needs to be covered up and removed from federal land. The truth is that the cross is simultaneously a war memorial and a religious symbol, which all the differentiating in the world will not separate the fusion of both into a complete union of religion and governmental authority.

- Salazar v. Buono, oral argument transcript, petitioners: pp. 3, 10, 11.

- Ibid., respondents: pp. 38, 39. Justice Scalia asserted that the cross is the “most common” symbol for all war dead. This implies the cross does not symbolically represent the deceased soldiers’ personal religious perspectives and is not a religious symbol per se. If Justice Scalia has his way, crosses as war memorials for deceased soldiers could stand alone on federal property. Of course, only those of a Christian perspective would think nothing wrong with a cross representing non-Christians as well. I mean no disrespect, being a Christian myself, but I sometimes have wondered about the incongruence between employing a cross to represent those who sacrificed their lives in battle in killing others for their country and the cross as a symbol of Jesus sacrificing His life for the sins of humanity in a cosmic battle without killing anyone in the process. Isn’t there a difference between justifiably fixing blame on others to kill them and taking the blame for others to save them?

- Hein had the practical result of leaving in tact a questionable cooperation between the executive branch and religious institutions with proselytizing motives performing social services for the public at government expense. Basically, no one has sufficient standing to contest practice, and it continues from presidency to presidency.

- Salazar v. Buono, oral argument transcript, petitioners: pp. 8, 9.