Desperate Faithful

Lawrence F. Kaplan September/October 2006

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Fadi has had it with Iraq. At his family's home in Baghdad, the Christian university student (whose last name has been withheld to protect his family) elaborates in fluent English. "There is no future for Christians here," he says. He knows this firsthand. Last year, four men drove up to his family's house and snatched his twelve-year-old nephew off the street. Targeted for riches that few of them actually possess, Christians routinely disappear from the sidewalks of Baghdad. "We have no militia to defend us, and the government—they do nothing," Fadi says. A day after the abduction, the captors phoned Fadi's family, demanding $30,000. If his family failed to cobble together the ransom, Fadi knew what would come next. His nephew would be shot or beheaded.

After Iraq's Baathists seized power in 1968, they celebrated by stringing Jews up in a Baghdad square. With the remnant of Iraq's Jewish population having long since fled the country, Christians have become today's victims of choice. Sunni, Shia, and Kurd may agree on little else, but all have made sport of brutalizing their Christian neighbors, hundreds of whom have been slaughtered since the U.S. invasion. As a result, Iraq's ancient Christian community, now numbering roughly 800,000 and consisting mostly of Eastern rite Chalden Catholics and Assyrian Orthodox Christians, dwindles by the day. According to Iraqi estimates, between 40,000 and 100,000 have fled since 2004, many following their own road to Damascus across the Syrian border or to Jordan, while many more have been displaced within Iraq. As for the country that loosed the furies against them, the United States refuses to provide Iraqi Christians protection of any kind.

From his synod in Baghdad, the most prominent Christian clergyman in Iraq, Chaldean Patriarch Emmanuel Delly, denies the obvious. "There is no persecution of Christians," the septuagenarian archbishop insists. "All Iraqis have problems." The fiction has become canonical among Iraqi Christian leaders, who maintain it to avoid inciting their tormentors. Many members of Iraq's clergy, for example, dismiss as gross exaggeration reports that tens of thousands of Christians have fled Iraq.

But, however much the clergy may deny it, Iraqi Christians suffer for their faith. Along with kidnappings and assassinations, church bombings—beginning with the destruction of five churches in August 2004—have become a staple of Christian life in Iraq. To disguise their faith, Christian women, particularly in Iraq's south, tuck their hair under hijabs

, while fewer and fewer attend church, performing Mass in homes and sometimes, like their ancient Christian ancestors, in crypts instead. Even the Kurds, so often depicted as saints in Iraq's morality tale, have taken to pummeling Christians; the Kurdish religious affairs minister said last year that "those who turn to Christianity pose a threat to society." Commenting on a recent pogrom against Christian students in Mosul, Yonadam Kanna, the only Christian elected to Iraq's new parliament, says, "The fanatics blame us for doing nothing. They blame us for being Christian."

The blame accrues, in part, because of real and imagined ties to the West and to the Western power occupying Iraq. There is, in truth, a cultural affinity between Iraqi Christians, many of whom speak English (and, as such, account for a large percentage of the U.S. military's interpreters), and the mostly Christian soldiers occupying their country. "[Local Christians] were very supportive of having us in Mosul," says Colonel Mike Meese, who served with the 101st Airborne Division in the heavily Christian city. "They'd have our soldiers go to Mass with them." But, as soon as their American protectors departed, the city's Christians became targets—their churches sacked and their archbishop kidnapped. In Baghdad, too, insurgents routinely execute Christians who work alongside the Americans. Threatened by her neighbors, a Christian friend of mine who worked in the Green Zone quit her job and today rarely leaves her house.

To the lengthy indictment of Christians, their persecutors have also added the charge of proselytizing. Unlike American soldiers, who mean to save Iraqi lives, the American evangelicals who follow on their heels mean to save Iraqi souls. There is deference. Evangelizing to Iraqis carries with it risks that evangelizing to, say, Latin Americans does not. The infusion of pamphlets and missionaries from organizations like the International Mission Board of the Southern Baptist Convention enrages Iraqi Muslims, who, Iraqi Christians leaders claim, increasingly conflate their congregants with "the crusaders"—and, too often, treat them as such. "The evangelicals have caused such problem for us," says Kanna. "They make the Sunni and Shia furious."

Even though Iraq's Christians suffer in the name of their American co-religionists, their fate seems not to have made the slightest impression on much of the evangelical establishment. Their websites and promotional literature advertise the importance of creating new Christian communities in Iraq while mostly ignoring the obligation to save ancient ones. Nor, with a few exceptions, have mainstream church leaders in the United States broached the subject, either. Dr. Carl Moeller, the president of Open Doors USA, an organization that supports persecuted Christians abroad, pins the blame on Christianity's own sectarian rifts. "The denominations in Iraq aren't recognized by Americans," he explains. "The underlying attitude is, 'They're not us.'"

The abysmal plight of Iraq's Christians, needless to say, long predates the arrival of the Americans. Since the first century, when Christianity first came to Nineveh province, Iraqi Christians have been cursed by geography. With its fields of mud burnt red by the sun, much of Nineveh—the ancestral home to a large number of Assyrian Christians that runs from Mosul to the Syrian border in Iraq's northwest corner—resembles a Martian landscape. Thousands of feet above the plains, a small U.S. outpost atop the Sinjar mountain range shines at night, a beacon to many of the Christians, Yazidis, and other persecuted minorities who populate the province below, a number of whom initially greeted the Americans as their saviors. But, having been massacred over the centuries by Ottomans, Kurds, and Arabs alike, most Christians know better than to rely on the goodwill of others.

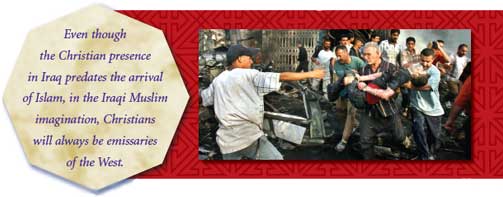

Nor is this knowledge merely the result of their experiences under foreign rule. Even though the Christian presence in Iraq predates the arrival of Islam, in the Iraqi Muslim imagination, Christians will always be emissaries of the West. Because they operate a disproportionate share of Iraq's liquor, music, and beauty shops—industries deemed sinful in various interpretations of Islam—insurgents accuse them of embodying the licentiousness of all things American and have burned hundreds of liquor stores to the ground. Where Iraq was once awash in pop music CDs sold by Christian vendors, a more recent CD circulating in Mosul features the beheading of Christians.

It was against this backdrop that Fadi's family raced to save his kidnapped nephew from a similar fate. Luckily, Fadi's father, a doctor, was able to produce the $30,000 ransom. Eight days after his abduction, the captors released Fadi's nephew. But the ordeal shook his family so badly that, a month later, they spirited the boy off to Jordan. "If, today, we all had a place to go, tomorrow there wouldn't be a Christian left in Iraq," Fadi says.

As for Fadi himself, who first applied to leave Iraq in 1998 while Saddam Hussein was in power, last year's kidnapping made him even more anxious to flee. With the doors to the United States sealed shut, he placed his faith in other Western countries. While over 40,000 Iraqi Christians have fled their homeland since the invasion, last year the United States permitted fewer than 200 Iraqis to immigrate. As for the thousands of remaining Christian refugees, until recently, the U.N.'s High Commissioner for Refugees didn't even bother referring their cases to the United States, knowing we had no inclination to take them in.

Their case files amount to proof of Washington's callousness. There is the Iraqi American whose Christian sister saw her husband gunned down in the street. Following the assassination of two more family members, the sister fell into a crippling depression, unable to care for her two-year-old child. Caught up in a bureaucratic tangle, her American relatives have gotten exactly nowhere. Another sister of an Iraqi American, a Christian woman with four children, lost her husband, killed while serving as a U.S. military interpreter. Her family, too, has been reduced to pleading her case before unconcerned State Department officials. A heartfelt advocate for Iraqi Christians, Representative Jan Schakowsky, a Democrat from Illinois, calls embassies, by her account, "at all hours of the night," but "the policy since the war began is, 'We're not granting asylum.' . . . There is no processing of refugees from Iraq." The reasons derive from post-September 11 security restrictions and, in the telling of a senior administration official, from the fiction that Iraqis, now liberated, no longer endure systematic persecution.

Fortunately for Fadi, other Western governments have offered a more candid assessment, and, after seven years of waiting, one just informed him he will be granted his visa. He can barely contain his glee. "I feel happy because I go to a new place where I feel free," he says.

But his case counts as a rare exception. Before leaving Baghdad last month, I got a taste of the desperation felt by Iraqi Christians left behind. Samira, a sad woman in her fifties who comes once a day to cook for an Iraqi friend, showed me a photograph of a woman in her thirties. She had a favor to ask: Would I marry her daughter? The proposition had nothing to do with me, per se. She simply wants to get her Christian daughter out of Iraq. Last year, insurgents murdered Samira's son. As a sign of respect, his Muslim friends transported the body to Najaf for burial in the Shia holy city. A kind gesture, to be sure, but Samira wants her son buried in a Christian cemetery. The son's Shia friends refuse to surrender his body, and, not being Muslim herself, there is no one to whom she can effectively—or safely—plead her case. Like most Iraqi Christians, she has nowhere to turn.

Lawrence F. Kaplan is a senior editor of The New Republic, and a well known author. He first wrote this piece for that magazine's April 3, 2006, issue. He writes from Washington, D.C.