Divided By Religion

Lincoln E. Steed May/June 2004

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

As our jet descended rather noisily through thin cloud cover toward Ambon airport in the Maluku province of Indonesia, what we saw suggested a tropical paradise. Turquoise waters revealed fascinating reef patterns from the air. The jungle-covered peaks behind Ambon city matched the great curve of a bay, that in the process of defining the shoreline from the airport to town, seemed to divide the island into two. What we saw in those moments before touchdown was a very natural illusion of tranquility. But since June 2000 the area has seen mostly violence. A violence that has pitted police forces against military units, village against village, and Christian against Muslim. A violence that has left thousands of homes, mosques, churches, and public buildings burned and gutted, caused hundreds of thousands to flee the province, and killed at least 5,000 people.

Three of us had taken a more than four-hour flight from Jakarta eastward across the Indonesian archipelago to Ambon. With me were John Graz, Ph.D., secretary general of both the Christian World Communions and the International Religious Liberty Association (IRLA), and Hiskia Missah, a religious liberty specialist based in Manila, Philippines. Missah, an Indonesian, had visited the area once since the violence began and was eager to see the progress toward peace. While the government had revoked its three-year state of emergency in September of 2003, at the time of our visit in late November 2003 the province still remained closed to tourists and journalists.

While the situation in Ambon may not have attracted the notice of the general public, overwhelmed as it was in the United States by September 11 and the ensuing invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, the religious liberty community has followed it very closely. Two years ago at an IRLA world conference in Manila we received an in-depth report from the area, including video footage of religious violence that went well into the bestial.

Then about the same time Graz and I attended a U.S. government hearing on the Ambon situation. Chaired by Elliot Abrahams, the committee brought in testimony from various experts and regional officials. It was confirmed that some of the spark for the violence had been provided by outside agents with Al-Qaeda connections, and that the local Muslim jihad group Laskar Jihad was receiving help from them.

One of the more troubling moments came during the testimony of an elderly community leader from the province. He attributed some of the violence to jealousy of the fine churches and overseas aid coming to the Christian community. Then, with his palms uplifted in supplication, he said, "Please understand we are a peaceful people. In fact, we never had such troubles till the Christians came." There was a collective sucking in of breath at this self-revelation. But things are rarely so one-dimensional, and we were eager to travel to Ambon and see for ourselves.

Indonesia is a large country in more than one sense. The nation is composed of thousands of islands in the world's largest archipelago, stretching from the island of Sumatra, southwest of Malaysia, eastward to West Papua (formerly Irian Jaya), which shares a land border with Papua New Guinea. Ambon is to the west of New Guinea and to the north of Timor. Even with so many small islands over a huge area of ocean, the landmass of Indonesia is almost three times the size of the state of Texas. The population is 235 million and is approximately 90 percent Muslim and only 8 percent Christian (5 percent Protestant, 3 percent Catholic).

The religious demographic explains much about Indonesia. While the nation is not an Islamic state, laws are heavily weighted toward Islamic norms and designed to protect Islamic control. For example, it is unlawful for Muslims and Christians to intermarry. And if a Muslim attends a Christian school, the school must provide Muslim teachers for him or her. When the focus turns to Ambon, there is a very significant demographic that surely explains why the religious violence could reach such a pitch: Ambon is nearly half Muslim and half Christian. With Ambon now the provincial capital for Maluku, and separatist movements asserting themselves there, it seems self-evident that the religious component would enter the violence and indeed become the defining parameter.

Once on the ground on Ambon Island, we made our way around the bay toward the city of Ambon, nominally a center of 300,000 persons. The trail of violence is marked by thousands of burned-out homes, churches, and other public structures. Even the 30-hectare campus of the Pattimura University, the most prestigious university in Maluku, is burned out and deserted. As we traveled our guides pointed out the religious affiliation of each area: "This is a Christian village; this is a Muslim area; now we are in a Christian area . . ." To an unknowing observer the distinction is hard to see; other than the dome of a mosque or a church steeple in the neighborhood, the people look the same, the lines between areas invisible.

We interviewed many Ambonese to get some sense of what had happened. Yes, they knew about the outside jihadis coming in to provoke violence, although it was an altercation initiated by a Christian taxi driver that seems to have sparked the killing. We were told of gangs of Christians and Muslims facing off in the very center of town: the Muslims shouting "Allah Akbar" and the Christians singing "Everybody ought to know who Jesus is" before both took to slashing the other side with machetes and shooting their opponents with high-powered firearms. As the violence spread, groups of fighters from both factions fanned out into opposing neighborhoods to torch houses and kill anyone that lingered at the scene. Some Christians told us a little too gleefully of how they had sent groups of small children to harass and burn Muslim areas: they called them agats, or small insects. But atrocities kept to no religious boundary: when some Christians took to cutting across the bay in fast boats, Muslim fighters intercepted them and cut them to pieces.

At first the local police, mostly Christian, tried to maintain order—perhaps with some partiality. Then the Indonesian military entered the conflict, on occasion leading mobs in attacks on police stations, then handing out the weapons to Muslim fighters.

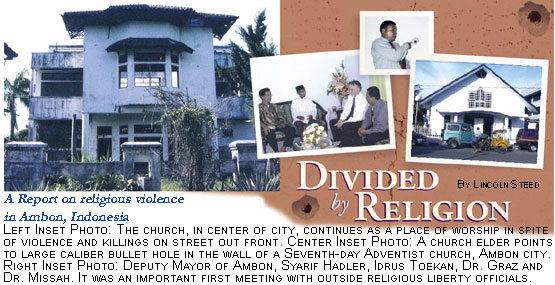

We visited a number of churches while in Ambon. The downtown Seventh-day Adventist church still stands, although there are large-caliber bullet holes in the wall and bullet-shattered woodwork behind the lectern. Members told us of many people shot down in the street outside, of snipers using the balcony to fire out of upstairs windows at a Muslim base in the hills above. There were many tales of deliverance and a recognition that without divine intervention many more would have been consumed by the violence. They told us of a young man who came and confessed to killing eight Muslims in revenge for the deaths of his parents and two siblings—he had then cut open his victims' chests and eaten their hearts. Can there be any more telling evidence of the bestial nature of religious violence!

It was the Muslim new year during our visit to Ambon. Because city offices were closed, the deputy mayor of Ambon, Sayarif Hadler, met us in his home in the Galunggung suburb, a Muslim stronghold during the violence. He welcomed us graciously, then introduced a special guest, Idrus Toekan, a Muslim community leader for the Maluku region.

"This is a very significant visit, " said Deputy Mayor Hadler after the introductions. "You are the first outside Christian leaders to visit us here. Do you realize that during the violence no Christian would dare come here? They would be killed on sight."

He then repeated what we heard many times in Ambon: that outside agitators had stirred animosity, but that within Ambon both Muslim and Christian leaders wanted peace, that they were committed to healing. He gestured toward a large floral display in his living room. "This is a gift from the Protestant Synod Headquarters downtown," he said. "They are wishing us a blessed new year. They show us Christian love." We had earlier visited the Synod leaders and had been impressed by their commitment to dialogue. General Secretary, Reverend S.J. Mailoa told us that they had kept to their post downtown even as buildings burned around them, including those of the nearby provincial legislature.

That same day in another Muslim district—Kebun Cengkeh—we met with H. Marasabessy, head of the department of religion for the Maluku province. Marasabessy was open and optimistic. "We must have the love for one another that Jesus Christ called for," he told us, borrowing from Christian teaching. "We must have dialogue. We must not allow outside agitation to interrupt the determination of our community to heal."

It is hard to predict where Ambon is headed. Is there a blossoming of dialogue and healing based on a shared commitment to community? Or are the wounds too deep, the differences too wide, the outside influences too much to resist?

In Jakarta the headlines in all the major papers warned of a "bloody Christmas" as a result of religious violence in Indonesia. That did not happen. In Ambon, reports were of several hundred jihadis in town for Christmas violence. It did not occur. Yes, there are groups who would continue to stoke the fires of religious intolerance for aims that are probably more political than religious. I note with some dismay that a Laskar Jihad commander, in a message reported by the BBC on May 16, 2002, condemned the peace efforts by both Muslim and Christian leaders in Ambon, and declared ongoing war; saying that "the second Afghanistan war will take place in Maluku."

What is hopeful for Ambon is the readiness of local political and religious leadership to work toward peaceful coexistence. What is needed is for Indonesia itself to become more protective of all religions, not just the majority faith. What is needed is for a world increasingly harassed by terrorism to avoid the trap of religious conflict that the terrorists are laying for all of us. What is needed is a "retreat" to faith solutions. While in Ambon I heard a church music group singing a plaintive chorus that translated into "Lord forgive us for what we have done, and for what we have done to others." And I must agree with Marasabessy that the solution to a community divided by religious intolerance lies in the advice to "love one another."

________________________

Photographs by Lincoln Steed

________________________

Article Author: Lincoln E. Steed

Lincoln E. Steed is the editor of Liberty magazine, a 200,000 circulation religious liberty journal which is distributed to political leaders, judiciary, lawyers and other thought leaders in North America. He is additionally the host of the weekly 3ABN television show "The Liberty Insider," and the radio program "Lifequest Liberty."