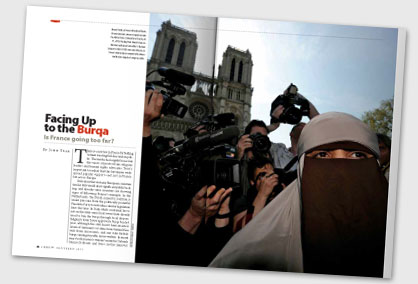

Facing Up to the Burqa

John Graz July/August 2011

There is a new law in France forbidding women wearing full-face veils in public. The media has largely focused on the voices of protest from religious leaders and human rights advocates. Yet it's important to realize that this law enjoys widespread popular support—not just in France, but across Europe.

Polls show that in many European countries similar bills would draw significant public backing, and already some countries are showing signs of following France's example. In the Netherlands, the Dutch minority coalition is under pressure from the politically powerful Freedom Party to introduce similar legislation later this year. In Italy, while a national law is not on the table some local towns have already tried to ban the burqa through local decrees. Belgium's lower house approved a burqa ban last year, although this still hasn't been enacted. Seven of Germany's 16 states have banned face veils from classrooms, and one state forbids burqas among its public sector workers. In recent years both Austria's women's minister Gabriele Heinisch-Hosek and Swiss justice minister Eveline Widmer-Schlumpf have been quoted as saying that a ban on public face veils should be considered if there's a significant increase in the number of women who wear them.1

So What's Driving This Trend?

According to French president Nicolas Sarkozy, the burqa ban represents an attempt to protect the dignity and equality of French women. Yet it's clear that the move to ban public veiling in France also contains a strong element of political calculation. President Sarkozy faces elections soon, and polls show he'll contend with strong competition from the far right. Many see this new law as a means by which Mr. Sarkozy can steal back support from this crucial voting bloc.

But there's more than just political strategy at work. France—and indeed, much of Europe—has a checkered history when it comes to dealing with religious minorities.

I recall the notorious "sect list" developed under France's anti-cult laws in the early 2000s—a list that on occasion was used by government agencies to deny rights to even well-recognized and long-established religions. Every minority group became a suspicious organization, and the result was not so much discrimination, but rather equality in discrimination.

And then there was the 2004 amendment to the French Education Code that effectively banned headscarves in public schools. Its enforcement became a media circus. Teenage girls who refused to take off their veils became "a national threat for the republic and the democracy."

Is the Burqa Different?

It's interesting to recall the reaction of the French government in November 2009 when the people of Switzerland voted in a referendum to ban the new construction of minarets. French foreign minister Bernard Kouchner said at the time that the minaret ban was "intolerant," "prejudiced," and amounted to "religious oppression."2

Yet now Mr. Sarkozy's government says banning the burqa has nothing to do with religion.

Is the burqa different? Is it a religious symbol or a symbol of female repression? Do women choose to wear the covering, or are they forced? Does the "burqa law" release women from an "oppressive, medieval practice"? Does it create a freer, more equitable society? Does it defend the rights and dignity of women?

Some would argue that a democratic state has not only the right but the responsibility to limit religious expression where this contravenes core cultural or social values. They reason: If the burqa ban can be questioned on the grounds of religious freedom, then what next? Could polygamy be protected? Or stoning those who decide to change their religion? Surely there must be a point where the state can say, "Stop. There is a limit."

Others argue that the new French law protects women from those who would force them to wear the burqa or niqab against their will. Few people would question the need for the law to defend the free choice of women in this way. But what about women who clearly assert that wearing the veil is an essential part of their religious expression, and they choose freely to wear it? In forcing women not to wear the burqa, is the French government also engaged in coercing women to act against their individual free choice?

And then there are the perennial issues of "culture" and "integration." When I go to the Middle East, or Asia, or Africa, I try to comply with some basic cultural norms. Could the French be right to say: "This is our culture, and we love it as it is. Nobody has forced you to come to our country, so if you come, don't impose your culture on us." Or as Damien Green, the immigration minister for the United Kingdom, said: "If you come to Britain, you have to accept British values." (Although it's very interesting to note that even though two out of three Britons support an outright ban on the burqa, the government refuses to propose a law.)

Enforced Integration?

I understand the concern of the French, but I believe that attempting to legislate cultural change is a hazardous enterprise that all too often steps on the toes of fundamental human rights. It raises the question: Who in society should have the task of arbitrating between competing social or cultural values? Who gets to decide which values should be promoted and protected, or which should be quashed? And if a religious practice happens to clash with another cultural value, should the "winner" be decided by majority opinion? Should the clash be decided by whichever political force is currently in power? Or are there deeper considerations to take into account?

The burqa law targets a specific population: the 6 million Muslims in France and, more specifically, the very small minority of women who wear the burqa or niqab. But attempts to integrate this group through legislation won't have the desired effect. This minority will simply grow in number and in frustration. True cultural integration can't be implemented through force; only education, encouragement, and the passage of time will ultimately prove effective.

And then there are purely practical problems associated with implementing this new law. Even if some agree with the assessment of Eric Besson, French minister of industry, that the burqa is a "walking coffin," how should the police proceed to make sure the law is respected? Will the police simply fine or arrest every woman wearing the burqa? And will the government choose to prosecute these cases, even if the women insist that wearing the burqa is a personal choice and an integral expression of their religious faith?

Too Far?

The French believe in integration. "You want to live with us, so follow our ways." American society believes in integration also, but it takes a less-demanding form. "You want to join us? You can keep your traditions and your religions, but obey our laws."

Religious freedom has a price and carries some risks. But in the long run a nation that attempts to protect its minorities rather than target them produces a society that is less polarized and, ultimately, more free.

Is France going too far? Is Europe going too far?

My answer is yes. Stripped of its fine-sounding rhetoric, this law simply codifies religious intolerance. It's religious prejudice masquerading as a defense of human rights. Simply put, President Sarkozy's government is saying to those women who wish to wear the burqa, "Our [majority] values are inherently superior to yours, and they trump your right to practice your faith."

But the inclination to fear or dislike that which is different is not just a French failing—it's a common human tendency. Before casting the first stone, every country should look at the way it treats its religious minorities.

1 "The Islamic Veil Across Europe," BBC Europe News, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-13038095, retrieved Apr. 19, 2011.

2 "European Politicians React to Swiss Minaret Ban," http://www.dw-world.de/dw/article/0.,4946616,00 retrieved Apr. 18, 2011.

Article Author: John Graz

John Graz is secretary-general of the International Religious Liberty Association.