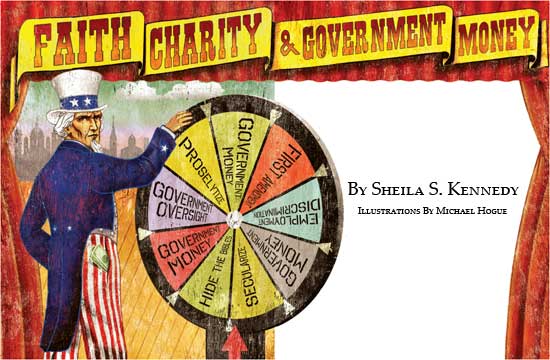

Faith, Charity and Government Money

Sheila S. Kennedy November/December 2008

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

In 1996, as part of a massive welfare reform bill, Congress enacted a provision that came to be known as "Charitable Choice," requiring government to partner with "faith-based" organizations (FBOs) on the same basis as other nonprofits to deliver services to the poor. The legislation was hotly debated, and later became the basis of President George W. Bush's much-touted "Faith-Based Initiative."

Whatever the merits or demerits of Charitable Choice, and whatever the rhetoric surrounding it, government partnerships with religious organizations are anything but new. Federal and state governments have partnered with religious organizations to provide social services since the beginning of government welfare programs.

A bit of history may be in order here: In 1965 a survey of 406 sectarian agencies in 21 states found that 70 percent of them were involved in some type of purchase-of-service contract with the government. A 1982 study of Protestant social service agencies in one Midwestern city found that some agencies received between 60 and 80 percent of their support from the government, and that approximately half of their combined budgets were government-financed. In 1994, still two years before enactment of the first Charitable Choice provision, government funding accounted for 65 percent of the nearly $2 billion annual budget of Catholic Charities USA, and 75 percent of the revenues of the Jewish Board of Family and Children's Services.

Given this history, we might have expected Congress to address several important questions in connection with Charitable Choice legislation: What kind of FBOs was this legislation targeting? How do the targeted organizations differ from religious organizations that have partnered with government for years? What are the barriers to their participation in social service delivery? To what extent are those barriers constitutionally required? What is the level of availability and interest, and what are the capacities, of these organizations? (Are there really "armies of compassion" just waiting to be asked to help the needy?) Few of these questions, however, were raised, let alone answered. In contrast to other portions of the welfare reform legislation, the record contains very little debate over Section 104.

Most of the congressional testimony supporting Charitable Choice reflected two assumptions: first, that government contracts had required FBOs to "secularize"—to remove religious icons and "hide the Bibles." Actually, studies show that this is simply not the case—very few religious contractors have experienced such demands. Second, support for Charitable Choice was based on the assumption that religious providers are more successful, that they do a better job at lower cost. In fact, there was no data either confirming or rebutting that presumption, because there was virtually no scholarship addressing the issue. Such evidence as existed was entirely anecdotal—and the plural of "anecdote" (congressional testimony notwithstanding) is not "data."

The most basic question raised by Charitable Choice legislation was "What's new?" It was quite obvious that the intended beneficiaries of this initiative were not the more traditional FBOs that had been doing business with government for decades. But how were the YMCA, Salvation Army, Catholic Charities, Jewish Welfare Federation, and countless other religiously-affiliated organizations that had historically partnered with government different from the glowing "faith-based" examples cited by supporters of the legislation? The answer seemed to be that government's traditional partners had been motivated by religion to provide purely secular social services—in other words, their religious beliefs led them to feed, clothe, and house the poor. The organizations cited by supporters of Charitable Choice, on the other hand, were in the business of spiritually transforming individuals. (Usually, this was euphemistically described as giving them "middle class" values.) What the champions of government funding for these organizations seemed not to understand was that using tax dollars for religious or spiritual transformation is forbidden by the establishment clause of the First Amendment.

In 1998 my research team began a three-and-a-half-year study of Charitable Choice. We compared the performance outcomes of faith-based and secular job training organizations.1 We looked at issues of capacity and accountability—the capacity of the targeted organizations to provide the services in question, and the capacity of state governments to work with and monitor them. We also wanted to understand how contracting with government affected smaller religious organizations. A number of ministers we talked to expressed concern that "with the government's shekels come the government's shackles," and it is certainly true that with government contracts come rules, regulations, and reports. How would small religious organizations cope with the fiscal and management burdens imposed by government reporting requirements? What about the dangers of becoming too dependent on government for funding? Would such dependence mute the church's prophetic voice?

Our final area of inquiry was constitutional. The media had focused primarily on the danger that social service contracting with unsophisticated providers might lead to proselytizing of vulnerable populations or to religious discrimination in providing the services in question. While those were understandable concerns, Charitable Choice raised a number of equally important but less obvious constitutional issues.

- Are nonmainstream and minority religions treated equally in this newly aggressive bid process? When government dollars are at stake, religious power struggles are inevitable. That was one reason the Founders separated church and state.

- Will government fiscal or programmatic monitoring rise to the level of entanglement for purposes of the Lemon test (or what is left of it?), thus infringing on the free exercise rights of religious contractors?

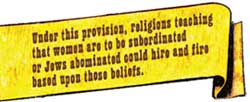

- What about the one provision of Charitable Choice that is undeniably new—the provision that allows FBOs to engage in employment discrimination even when the jobs in question are being funded by tax dollars? Under this provision, religions teaching that women are to be subordinated or Jews abominated could hire and fire based upon those beliefs. While religious organizations are already exempt from certain civil rights laws, those exemptions generally apply when they are spending their own money, not when they are using tax dollars.

The employment discrimination issue goes to the heart of the debate over what we mean by a "level playing field." First Amendment separationists and accomodationists both will agree that religion should not be disfavored by government. The ideal is neutrality, with religion receiving neither extra burden nor special benefit. Despite considerable evidence to the contrary, supporters of Charitable Choice insist that FBOs have been the victims of antireligious bias, and that the legislation was necessary to correct that situation.

This element of the debate has become particularly fascinating, because what many proponents of Charitable Choice are advocating is essentially "affirmative action" for religious nonprofits. When Massachusetts, for example, declined to do special outreach to FBOs and continued to apply the same rules to all bidders, religious and secular, the Center for Public Justice criticized the state for failing to "affirmatively act" to implement Charitable Choice. In this view, implementation requires "special" outreach and rules rather than equal treatment.

Some Charitable Choice supporters have argued that faith organizations should be exempted not just from antidiscrimination laws, but also from licensing requirements that apply to all other bidders. Les Lenkowsky, for example, has argued that "pastoral counseling" certification should be considered the equivalent of social work degrees or drug treatment credentials. (What makes this even more interesting is that virtually all of the proponents of special rules for FBOs are adamantly opposed to affirmative action for racial minorities. This is noteworthy on two levels: the philosophical inconsistency, and the fact that the vast majority of FBOs we talked to don't believe that bending licensing rules to benefit religious entities is either necessary or desirable.)

None of this, no matter how interesting, gives us an answer to the underlying question: If numerous FBOs were already participating in the provision of welfare-related social services, and if there was little or no social science data addressing comparative effectiveness, what was the real impetus for Charitable Choice?

Some commentators dismiss the enthusiasm for faith-based partnerships as a cynical attempt by Republicans and President Bush to play to the Christian Right, an important constituency. But I think this explanation ignores the bipartisan embrace of these initiatives, their timing, and the general political context within which they have emerged. It is far more illuminating—and arguably more accurate—to view Charitable Choice and its progeny as part of the "reinvention" trend that has been reshaping governments, particularly at the state and local level, for at least the past 25 years. "Reinvention" and "privatization" have involved the vastly increased use of private for-profit and nonprofit providers to deliver government services.

While governments have always purchased goods and services—including social services—in the market, the enormous growth of contracting out, where services are increasingly provided and paid for by government but delivered by for-profit or nonprofit contractors, raises significant constitutional and public policy issues.

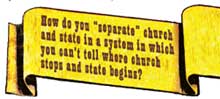

- Are these public sector partnerships with businesses and nonprofit organizations creating a new definition of government? Is this form of privatization extending, rather than shrinking, the state? That is, does the substitution of an independent contractor for an employee really mean there has been a reduction in the scope of government, as proponents believe? Or does the substitution operate instead to shift the location but not the scope of government activities, blurring the boundaries between public and private and making it more and more difficult to decide where "public" stops and "private" begins?

- If we are altering traditional definitions of "public" and "private" by virtue of these new relationships, what will be the effect of that alteration on a constitutional system that depends upon the distinction to safeguard individual rights? If workers in nonprofit agencies are executing government contracts, logic would compel us to consider them government agents. Current law rarely does so. But in our constitutional system, only the government can violate the Bill of Rights. When we fail to identify contractors—religious or secular—as government agents, we lose the right to hold them to constitutional standards. How do you "separate" church and state in a system in which you can't tell where church stops and state begins?

- When government is providing a service—whether directly or through an intermediary—government must ultimately be accountable for that service. Public officials can't simply give tax dollars to organizations—no matter how saintly they may seem—and just trust that good things will happen. There is a fiscal and constitutional duty to confirm that public dollars are appropriately spent. What is appropriate, of course, depends upon our goals. And that takes us nearly full circle.

In a very real sense, this whole debate is a throwback to some of our oldest conflicts about social welfare policy, and the "deserving" and "undeserving" poor. If poor people need help because they are disabled, or because the factory closed, or because other problems have disadvantaged them, then we focus on giving them food, jobs, or shelter. If, however, poor people are poor because they lack virtue, because they are morally defective, then the goal is not merely to feed, house, or educate them; it is to transform them.

Whatever the underlying dynamics, the question is not whether government should cooperate with faith communities. It always has, and presuming the continuing vitality of both the religious sector and the equal protection doctrine, it always will. The real questions are: When? How? Under what circumstances? With which providers? For what purposes?

Those questions may not be useful when devising handy political slogans, and they don't adapt well to bumper stickers. But we need to answer them if we are going to serve people in need while remaining faithful to the Constitution.

Sheila S. Kennedy is professor of Law and Public Policy at the School of Public and Environmental Affairs at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis.

1 Our findings and methodology, as well as the sources for other information contained in this article, are detailed in Charitable Choice at Work : Evaluating Faith-Based Job Programs in the States, published in 2006 by Georgetown University Press. In brief, we found that religious and secular organizations placed a similar number of clients in jobs at comparable rates of pay; however, those placed by secular organizations worked more hours each week and were much more likely to have jobs offering benefits such as health insurance.