Far From Home

Giacomo Sini March/April 2019Every morning in a quiet village of Nordrhein, Germany, a few miles from Belgium, Khder after breakfast embraces his wife Nadjat, gives a kiss to their 4-year-olds sons and goes by bus to Nideggen train station. A local train, after winding through woods and fields dominated by wind turbines, leads him in an hour to Düren, where he attends German-language classes in a class reserved for asylum seekers only.

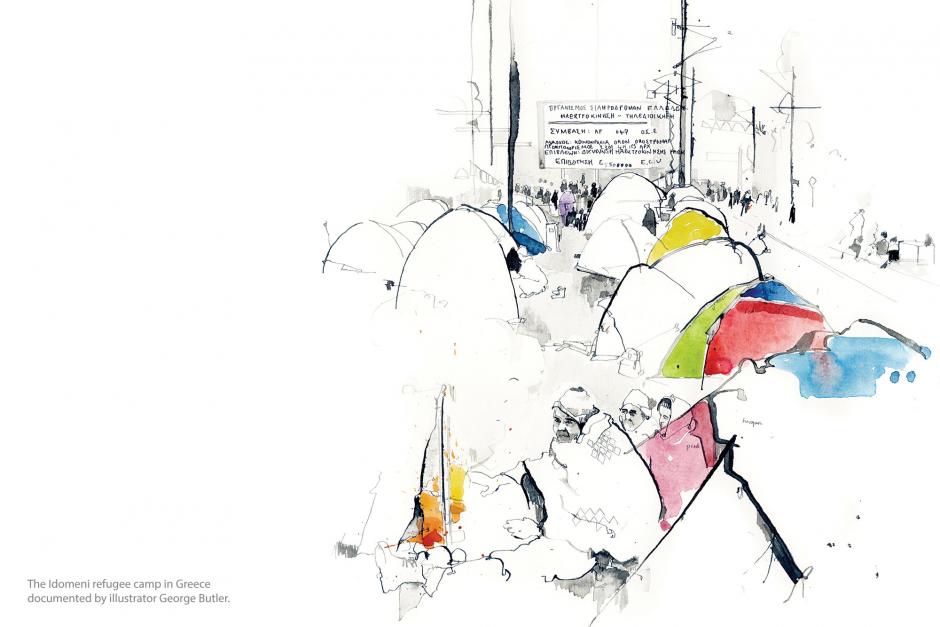

Khder is 27 years old and belongs to the Yazidi (or Êzidi) religion; he comes from the Sinjar plateau in northern Iraq. Three years ago he was stuck with other coreligionists in the infamous Idomeni refugees’ camp, between Greece and Macedonia.He had recently arrived with his family in Lesbos from Turkey by way of one of the many overflowing barges. Before leaving his homeland, he was a security guard.

The religious group of the Yazidis to which Khder belongs is composed of more than 1 million people, and is originally from the northern Iraqi province of Nineveh, sharing the same language and much of the Kurdish culture of Turkey and northern Syria. This cult, centred on the veneration of Seven Angels, precisely because of its Gnostic and pre-Islamic nature has become one of the main goals of the ethnic cleansing operated by Daesh in the region. As with both the Shiites and Christians, Yazidis are a special target .

During an August 2014 offensive aimed at conquering northern Iraq, the jihadist militias besieged the Sinjar plateau, committing a massacre that claimed the lives of more than 5,000 people, enslaving thousands of women and forcing many to convert to Islam. Those who, like Khder, survived the attacks, managed, after being trapped for days on the mountains without food or water, to take the road to Europe, thanks to a humanitarian corridor—opened by the Kurdish guerrillas of Ypg-Ypj, “People’s Protection Units and Women’s Protection Units”—toward Rojava, in northern Syria, governed by them.

Thejourney to Germany was anything but easy for Khder. He spent almost four years in tent camps, first in Turkey and then in Greece. It was a time of constant emergency, and he lived under precarious conditions. After trying several times to cross borders illegally, he managed to obtain permission from the German state to get on a plane and land in Monaco, where he then obtained asylum valid for one year. Through the BAFM—“Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge,” the German federal office that deals with refugees, directly managed by the Ministry of the Interior—Khder received a room and a shared kitchen with two other refugee families from the Middle East, in a modern home nestled in the countryside of Nideggen. Now with his wife, Nadjat, and two children he is happy and relaxed, with the intent to do everything possible to become a full European citizen; although with the constant fear of being repatriated to Iraq, where some of his relatives still live, unable to leave.

“Every six or seven months I am called for talks for the renewal of asylum, where we are registered with a video camera. If there is any inconsistency between one registration and the other, the risk of repatriation is highly expected,” says Khder over tea and a Kurdish-style lunch prepared by Nadjat. “A Yazidi family we know has been sent back to Sinjar. More than 1,000 others are instead in Greece waiting for the relocation.”

An asylum seeker in Germany has the opportunity to study or work. The state takes charge of economic maintenance according to the needs and the type of family. Language lessons are daily and do not last more than four hours, but a delay may be enough to reduce the incentives received on a monthly income that in the case of Khder does not exceed 700 euros.

Khder finds relations with Turkish or German neighbors excellent. They pass him books for his lessons, often give a lift or invite him to their homes. Nadjat cannot attend the same courses as her husband because the children do not yet attend kindergarten. The two children, however, while conversing with their parents, repeat numbers and words in German, in English, in Greek, in Turkish: all languages listened to while on their endless exodus. When he is not at school, Khder offers himself as a volunteer translator to help other Yazidis or Muslim refugees in bureaucratic or health-related practices. Otherwise his days are occupied by games in the yard with the children or punctuated by calls from family members still in tents in Zakho refugee camp in Iraqi Kurdistan or Diyarbakir in Turkey, or scattered between Germany and the Benelux.

He is part of a transnational community that, like others, keeps alive thanks to the networks offered by the new means of communication. If someone reminds Khder of the homeland he fled, he suddenly changes the topicor his face darkens: “I would lie if I said that I’ve not been missing Sinjar, but nothing can ever change there. I’m just trying to forget the past and build a new life for me and my family.”

One Sunday Khder managed to get in touch with Saed, another 23-year-old Yazidi he met in Idomeni. The young man now lives in Euskirchen, a medium-sized town an hour and a half away from Nideggen. He works as a warehouseman for the DHL company. Saed’s father was kidnapped by Daesh, and there has been no news of him for four years. But Saed’s cousin Jamal managed to get to Germany, through the Balkans, before the borders were closed in 2015.

To facilitate integration and hinder the division between ethnic groups, the Yezidis have been placed, as other asylum seekers, in many regions of Germany. Each city or village, depending on their size, is allocated a certain quota of refugees. Saed says, however, that it is sometimes almost impossible to make friendships and create relationships with local people, because many continue to be suspicious of newcomers or equate all of them under the stigma of Islamic fundamentalists, “Often someone asks me why I fled from Iraq or why I’m not going back there,” he says.

Away from the industrial areas of the Ruhr and near Schwandorf, a medieval village crossed by the Naab, within the region of Bavaria, is a center that temporarily houses more than 100 refugees. Here are Saif and Aylan, both 24 years old and Yazidis. The structure they live in is a prefabricated building, onlya year or two old.Here other Iraqi Kurds, Syrian Christians and Muslims, Afghans and families from the Horn of Africa, live harmonically. The kitchen and bathrooms are shared, and everyone is free to enter and exit when they wish: there are no checks at the entrance, and the police are rarely seen.

Saif, in Germany for two years, has already achieved a B2 level in German language.His life story has excited even a Breton film director, who included him in a documentary entitled “Open the Border,” done in association with television channel France 3.

During the siege of Sinjar, Saif fell into the hands of the militiamen of the Islamic state. The following day he miraculously managed to escape with the help ofKurdish guerrillas from Rojava. Then on the sea voyage from Turkey to Greece he witnessed six of his compatriots die. At the airport checkpoint in Greece his false Greek passport was refused and he was sent back to Turkey.Paying another 3,000 euros, he shaved, got a tattoo on his neck, bought a German passport, and with this finally managed to board a flight for Italy. He landed in Milan with a Syrian girlfriend; he managed to take a train for Germany and elude customs inspections. When he arrived in Munich,Saif immediately initiated asylum application procedures.

Now Saif dreams of reaching his parents (who live in the United States), even if it means losing the chance to return to Germany, where he now feels at home and has many friends, both Yazidis and Germans. “Who knows, one day here I could also resume my studies interrupted in Iraq. I wanted to become a biologist,” hesays while walking in the streets of Schwandorf .

Three years ago when Yazidis were stalled in Greece and living in tents, theycelebrated a New Year’s Eve, the Çarşema Sor, a spring festival that, like the Newroz Kurdish, celebrates the birth of the world, the awakening of life and nature. Today this idea of rebirth takes even greater significance for those who have succeeded in reaching Europe.

But despite the fact that almost 120,000 Yazidis have been sheltered in Germany, many have been killed by Daesh, are missing, or are still struggling between life and death in refugee camps in the Middle East, sharing the same fate as thousands of other refugees from wars. Perhaps one day the West will better remember the tragedy and genocide of this people for centuries persecuted.Somehow humanity needs to be able to give a new future, a real rebirth, to all its children who are exiled in this tumultuous world.

Article Author: Giacomo Sini

Giacomo Sini is a photojournalist writing from Italy.