Final Summum

Holly Hollman March/April 2009

In November the Supreme Court of the United States heard a case that presents an interesting twist on the persistent constitutional problem of religious displays on government property. Typically, the question is whether a particular display, such as a depiction of the Ten Commandments or a Nativity scene, violates the establishment clause of the First Amendment.

Pleasant Grove City, Utah v. Summum involves a dispute over a religious display that defied the usual order of events. Instead of challenging a religious display on city property as unconstitutional, a small religious group claimed they had a right to display a monument reflecting their beliefs, as well. While the case offers a compelling factual setting for examining the proper relationship between religion and government, it will be decided without reliance on the constitutional provision best designed to protect that interest.

The Case at Hand

The dispute began when Summum, a New Age religious sect based in Utah, sought to display a monument depicting its teachings, known as “Seven Aphorisms,” in Pleasant Grove City’s Pioneer Park. According to news reports, Summum was established in 1975 and operates out of a pyramid building in Salt Lake City. The group is known for a belief system steeped in meditations and for practicing mummification, as well as for its litigation in several Utah cities. Summum designed a monument similar in size and appearance to other privately donated monuments in the park, including a Ten Commandments monument donated by the Fraternal Order of Eagles in the 1970s. When the city denied their request, Summum sued, arguing that the city had discriminated against them in violation of their rights under the First Amendment’s free speech clause. From Summum’s perspective, Pioneer Park was a “public forum,” the kind of open space traditionally used by individuals to distribute messages

In November the Supreme Court of the United States heard a case that presents an interesting twist on the persistent constitutional problem of religious displays on government property. Typically, the question is whether a particular display, such as a depiction of the Ten Commandments or a Nativity scene, violates the establishment clause of the First Amendment.

Pleasant Grove City, Utah v. Summum involves a dispute over a religious display that defied the usual order of events. Instead of challenging a religious display on city property as unconstitutional, a small religious group claimed they had a right to display a monument reflecting their beliefs, as well. While the case offers a compelling factual setting for examining the proper relationship between religion and government, it will be decided without reliance on the constitutional provision best designed to protect that interest.

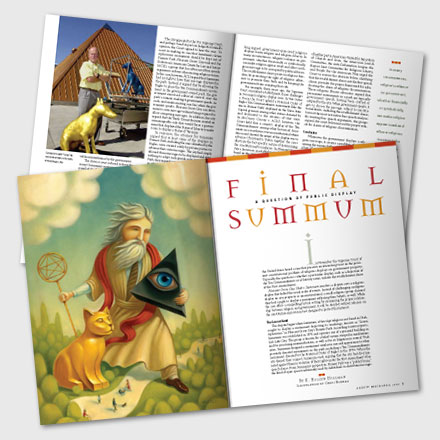

Summum founder “Corky” Ra and some artifacts of his faith. AP Photo/Douglas C. Pizac

The Case at Hand

The dispute began when Summum, a New Age religious sect based in Utah, sought to display a monument depicting its teachings, known as “Seven Aphorisms,” in Pleasant Grove City’s Pioneer Park. According to news reports, Summum was established in 1975 and operates out of a pyramid building in Salt Lake City. The group is known for a belief system steeped in meditations and for practicing mummification, as well as for its litigation in several Utah cities.

Summum designed a monument similar in size and appearance to other privately donated monuments in the park, including a Ten Commandments monument donated by the Fraternal Order of Eagles in the 1970s. When the city denied their request, Summum sued, arguing that the city had discriminated against them in violation of their rights under the First Amendment’s free speech clause. From Summum’s perspective, Pioneer Park was a “public forum,” the kind of open space traditionally used by individuals to distribute messages without interference by the government.

The district court refused to force the city to accept Summum’s monument. But a three judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit reversed, holding that Pioneer Park was a traditional public forum and that the city had unlawfully excluded Summum. Under the public forum doctrine, the government is strictly limited in its ability to restrict speech, and discrimination based on the viewpoint or identity of the speaker is prohibited.

At a glance, the result of the Tenth Circuit’s decision appears only fair: if the city allows a religious monument offered by some of its citizens, how can it reject one from others? The rationale for the decision, however, obscured the point. The court’s holding that Pioneer Park was a traditional public forum threatened to have far-reaching consequences. It was interpreted as opening the door to a parade of horribles, possibilities such as requiring governments to “either remove the . . . memorials or brace themselves for an influx of clutter,” as Judge Michael McConnell, an influential expert on the law of religious freedom, said in his dissent from the denial of rehearing by the full court.

The city appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, and perhaps based in part on Judge McConnell’s opinion, the Court agreed to hear the case. To assist in making its case that Summum’s Seven Aphorisms monument should be kept out of Pioneer Park, Pleasant Grove City enlisted Pat Robertson’s American Center for Law and Justice (ACLJ), a group that has often used free speech arguments in favor of protecting religious voices. In this case, however, ACLJ argued that Summum had no right to have their message displayed in the park. Instead, it argued that by allowing the Eagles to place the Ten Commandments monument in the government-owned park, the government exercised editorial control over the park’s content, making it government speech. As such, and under existing case law, when the government speaks, Pleasant Grove City can determine its own message without being required to allow competing messages. In addition, the city argued that the Tenth Circuit decision created an unmanageable rule that would force a government that displayed the Statue of Liberty to make room to display a Statue of Tyranny.

In response, the attorney for Summum argued that at least some of the displays in Pioneer Park, including the one submitted by the Eagles, were created solely by private parties to advance their own messages. The city had simply allowed those messages to be displayed and done nothing to adopt such speech as its own. Pioneer Park, they argued, was a traditional public forum in which the city may not discriminate among speakers based on the content of the speech or identity of the speaker. Summum argued that the city’s “government speech” claim was simply a theory conveniently adopted to keep Summum out of the park.

The Establishment Clause: The Elephant in the Courtroom

Conspicuously missing from the pleadings in the case was the question of whether the city had violated the establishment clause. For reasons having to do with peculiarities of Tenth Circuit case law, Summum pursued its lawsuit based on the free speech clause of the Constitution, not the establishment clause. As a general matter, reviewing courts are not free to introduce legal theories that have not been raised by the parties, even when those theories may be more obviously relevant to the case at hand.

This is unfortunate because the establishment clause provides the proper framework for considering government-sponsored religious displays, as well as adjudicating claims of denominational preference and religious animus. As many religious liberty advocates have long argued, government-sponsored religious displays harm religion and religious liberty. In many circumstances, religion’s reliance on government, whether financially or symbolically, can make religion appear weak and allow a religious message to be corrupted by political forces. The establishment clause protects religious freedom by protecting the right of religious adherents to promote their faith and by keeping the government from usurping that role.

For example, three years ago, the Supreme Court considered establishment clause challenges in two major religious display cases. In Van Orden v. Perry, the Court upheld a Fraternal Order of Eagles Ten Commandments monument (like the one in Pioneer Park) displayed on the Texas State Capitol grounds among other statues donated by and dedicated to the citizens of that state.

In McCreary County v. ACLU, however, the Court held that a county’s display of the Ten Commandments among other historical documents in a courthouse was unconstitutional where the record showed the intent of the display was to advance Christianity. Taken together the cases illustrate the fact-specific nature of determining the constitutional boundaries. In Pleasant Grove City v. Summum, an establishment clause challenge based on the city’s posting of one religious monument, paired with the rejection of another, could have made a stronger case for unconstitutionality.

Even though establishment clause concerns were missing from the parties’ briefs, they quickly appeared during oral arguments. As Chief Justice John Roberts said to counsel for Pleasant Grove City, “You’re really just picking your poison, aren’t you? I mean, the more you say that the monument is government speech to get out of the . . . free speech clause, the more it seems to me you’re walking into a trap under the establishment clause. If it’s government speech, it may not present a free speech problem, but what is the government doing speaking—supporting the Ten Commandments?”

Other questions from the bench indicated that the justices were dissatisfied with a result that would deem the monuments private speech and lead to the government having to display all kinds of bizarre messages of its citizens if it allowed any displays. The justices also expressed skepticism that the city could avoid discrimination by simply applying the label of “government speech” to preferred monuments. While the parties offered approaches that appeared to be all or nothing, Justice David Souter suggested that some monuments may be a mixture of private and public speech that defied the purely “private” or “government” categories the parties proposed.

In a friend of the court brief filed on behalf of neither party, Americans United for Separation of Church and State, the American Jewish Committee, the Anti-Defamation League, the

Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty, and People For the American Way urged the Court to reverse the decision below, clarifying that the establishment clause, not the free speech clause, provides the proper framework for adjudicating the claim of religious discrimination. These religious liberty advocates argued that permanent monuments in a park are typically government speech, having been crafted or adopted by the city. When government speaks, it gets to choose the message, subject to constitutional limits, including the establishment clause, but not the most restrictive free speech analysis. By inviting free speech arguments, the groups argued, the court below missed the proper vehicle for claims of religious discrimination.

Conclusion

Whenever the government displays a religious message, it creates a problem of picking among the various faiths of its citizens. Even displays of widely accepted teachings such as the Ten Commandments involve the theological decision of which version (Jewish, Catholic, or Protestant) will be represented. A government bound to serve its citizens without regard to religion is hardly the appropriate authority to make such decisions. Even in those contexts in which religious displays have been upheld, it is hard to avoid the sense that government is showing a denominational preference, violating a central concern of religious liberty law. That concern is explicit in the facts alleged in Summum’s case.

As the Court heard its only religious liberty case this term, many listeners regretted that unless and until the case is reversed and pursued under a different theory, Summum cannot win under the clearest command of the establishment clause—prohibiting denominational preference. The path for the parties remains muddled. Perhaps the city will win, despite concerns that government may have acted out of religious animus. Perhaps the Court will clarify the “government speech” doctrine in ways that limit the ability to exclude messages based upon the substance or speaker. Perhaps the Court will establish a hybrid theory to analyze cases that have aspects of private and government speech. In any event, while the case offers little opportunity to impact religious liberty law, it stands as an important reminder to those who value religious liberty that a government that promotes the religion of some of its citizens threatens the religious liberty of others.

Article Author: Holly Hollman

Holly Hollman serves as general counsel and associate executive director of the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty, where she provides legal analysis on church-state issues that arise before Congress, the courts, and administrative agencies. She is a member of the U.S. Supreme Court, D.C. and Tennessee bars.