First Freedom: The Fight for Religious Liberty - The Film

Gregory W. Hamilton May/June 2013What is the truth when it comes to understanding the constitutional principles of the separation of church and state, and the free exercise of religion? In today’s passionate melee over the Health and Human Services’ “contraception mandate,” and on other issues such as gay marriage, school prayer, the placement of Ten Commandment monuments in public buildings, or the direct funding of private and religious schools by federal and state governmental entities, factions on both the religious and political Left and Right are co-opting and invoking the nation’s constitutional Founders. Many summon them ignorantly and incredulously.

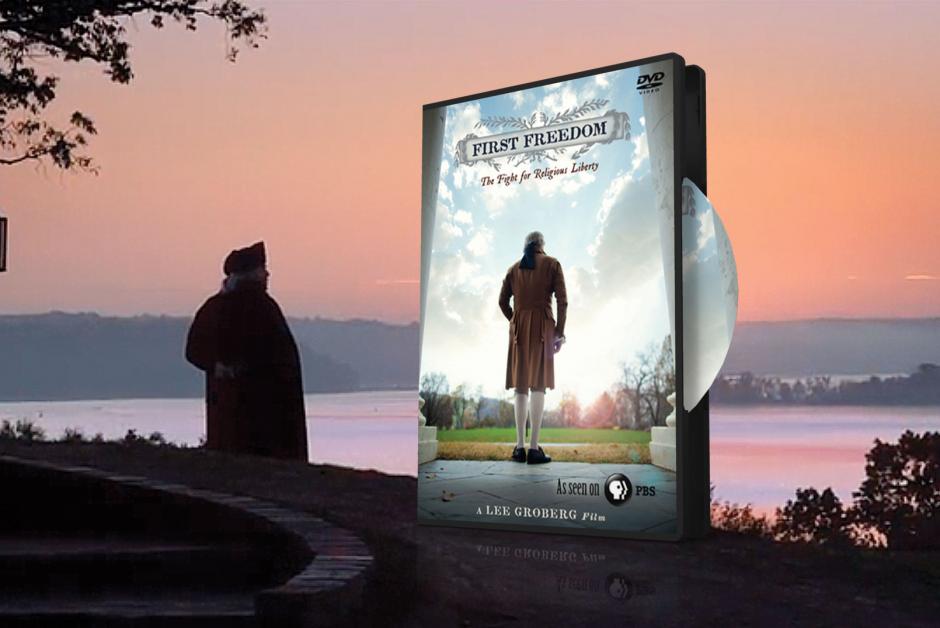

In an effort to bring clarity to the public view, the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) entered the national discussion in December last year by airing First Freedom: The Fight for Religious Liberty. The production represents a masterpiece of the blended, nuanced views of center-, center-Left-, and center-Right-leaning scholars in a unified presentation on how our country’s constitutional Founders separated the supervisory and regulatory power of the state from the church, and the manipulating and coercive power of the church from the state. The Founders recognized that a truly successful democratic republic could never survive without making both the church and the state independent and free. This distinction is worth noting because PBS, and the cast of scholars it chose, have made very clear the stark differences between America’s puritan and constitutional founding periods. The Great Awakening is presented as neccessary to make sense of the theological, cultural, and political seeds of the American Revolution and the gradual transition between these two main periods of American history.

“A City Upon a Hill”

America’s nascent journey toward religious freedom sprang from both religion and politics. It began with the English Pilgrim Separatists who settled Plymouth Colony upon their arrival on the Mayflower in 1620. They were Puritans who broke away from the monarchical Church of England because they felt they had not completed the work of the Protestant Reformation. This, they believed, was because of the church-state unity that corrupted both the state and the church’s “separate but holy” duties. The Congregationalist Puritans were given a royal charter to settle what would become the Massachusetts Bay Colony centered in Plymouth, and later in Boston. These Puritans accepted some of the customs and rights of the Church of England and defined church-state collaborations for their own holy and utopian societal purposes.

But the seeds of their own unraveling came through their lack of tolerance for dissension, usually resulting when anyone expressed a differing point of view. This led to the martyrdom of evangelical pioneer Mary Dyer, the banishment of Anne Hutchinson, the Salem witch trials, in which 20 women and girls were put to death, and the subsequent persecution and exile of Roger Williams. He was the inspiration for future Baptist pastors such as Isaac Backus and John Leland, who would go on to nurture Williams’ heretical doctrine of church-state separation in the minds and hearts of America’s Revolutionary Founders, particularly Thomas Jefferson and James Madison.

The Great Awakening and the Road to Revolution

The PBS special moves gradually from the Puritan colonial years to the First Great Awakening, in which evangelicalism began to sweep all the colonies—north, middle, and south. According to Colonial period scholar Jon Butler from Yale University, this period was particularly significant because the Congregational Puritan Church gradually became the stepchild of the government, and no longer the master. Clergy came under fire for increasingly boring sermons as the Dutch and English field preachers, inspired through the charismatic and winsome ministry of the great revivalist George Whitefield, spread the emancipating message of universal salvation through Christ. Whitefield’s sermon tracts, as well as his preaching throughout all the colonies, gave birth to America’s First Great Awakening.1

What remained constant in both the Puritan and First Great Awakening periods was the idea that America was the new Israel in a new Promised Land. What changed was the insertion of a revolutionary cause whose message was universal salvation and freedom through Christ alone, and not by way of a king, a specific denominational polity, or government. Religious pluralism, largely a Protestant phenomenon, germinated the spirit of democracy and antiestablishmentarianism.2

The Quebec Act, passed by the British Parliament in 1774, inflamed many in the colonies. It replaced the previous oath of allegiance with one that no longer made reference to the Protestant faith. It guaranteed Catholics the freedom to worship and practice their faith. It restored the Catholic Church’s right to impose tithes. American Protestants saw this act as a sign that they were becoming increasingly hemmed in and surrounded by Catholics to the north in Canada, Catholic Spaniards to the south in Florida, and Catholic Francophiles in Louisiana. It had the effect of augmenting the growing revolutionary fervor in America against Britain.

Declaration of Independence Coincides With Virginia’s Declaration of Rights

When Parliament replaced the Toleration Act of 1689 with the Coercive, or Intolerable, Acts of 1774, it represented a frontal assault and rejection of John Locke’s Two Treatises of Government,3 which had been published in London in 1689. Locke’s central premise was that individual rights, equal rights, were inalienable and came from God and not kings. The educated elite in the American colonies took immediate note of this significance. Therefore it is not surprising that the very language of Thomas Jefferson’s authorship of the Declaration of Independence had John Locke written all over it in philosophy, message, and tone, serving as a corresponding assault on King George III and the so-called divine right of kings:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”4

In this mix of heady revolutionary talk was Virginia’s Declaration of Rights, drafted by George Mason in May of 1776, with a special section emphasizing religious freedom authored by James Madison. Unanimously adopted on June 12, 1776, by Virginia’s Convention of Delegates, it too had John Locke’s name written all over it. The Virginia Declaration of Rights influenced the Declaration of Independence (drafted in June and ratified on July 4, 1776), the United States Bill of Rights, and the French Revolution’s Declaration of the Rights of Man (1789).

Section XVI of the Virginia Declaration declared: “That religion, or the duty which we owe to our Creator and the manner of discharging it, can be directed by reason and conviction, not by force or violence; and therefore, all men are equally entitled to the free exercise of religion, according to the dictates of conscience; and that it is the mutual duty of all to practice Christian forbearance, love, and charity towards each other.”5

Then, on June 12, 1788, James Madison, the unsung hero and little known father of the United States Constitution, made this brilliant observation to the delegates at Virginia’s ratifying convention regarding how freedom of religion was to be achieved and how it was the central basis for the hope of any successful experiment with a constituted democratic republic: “Is a bill of rights a security for religion? . . . If there were a majority of one sect, a bill of rights would be a poor protection for liberty. Happily for the states, they enjoy the utmost freedom of religion.” “This freedom,” Madison argued, “arises from that multiplicity of sects, which pervades America, and which is the best and only security for religious liberty in any society. For where there is such a variety of sects, there cannot be a majority of any one sect to oppress and persecute the rest.”6

In the fall of 1788 Madison, in his extensive correspondence with Thomas Jefferson, said that he was “in favor of a bill of rights” if it was “so framed as not to imply powers not meant to be included in the enumeration.”7 In other words, it was assumed that since Congress possessed no power to interfere with basic rights, the Constitution alone would be enough. The problem remained, Jefferson argued, that such basic rights had yet to be spelled out in a formal guarantee. But Madison persisted in reasoning that certain essential rights, particularly the rights of conscience, could never be fully guaranteed by law.8

James Madison—Getting It Right

At the first session of Congress in 1789, the House of Representatives and the Senate wrote separate draft language for what they thought should be the wording of the establishment and free exercise clauses of the First Amendment.

On the House side, James Madison led the way, bringing to the table his vast experience in drafting the religious freedom section in Virginia’s Declaration of Rights, Section XVI, and from his long fight with Thomas Jefferson to pass Virginia’s Statute for Religious Freedom. Madison had also defeated Patrick Henry’s “Bill Establishing a Provision for Teachers of the Christian Religion.” Madison’s leadership produced drafts that avoided language that would open the door to nonpreferential or so-called nondiscriminatory types of funding for churches and private religious schools, or for constitutional amendment language stating that the nation was a “Christian nation.”

The religion clauses of the U.S. Constitution continue to produce the same divide between those who seek to keep church and state as separate as possible and those who seek to have government both sponsor and fund faith-based charities, institutions, and schools. In the PBS special, Professor Robert George of Princeton University subtly but clearly argues that the religion clauses were meant by the constitutional Founders to foster “the right to bring faith into the public square.”9

“How far, how little?” are the obvious questions that remain with us today. Does this mean government sponsorship of prayer in public schools, or government funding of religious ones? Professor Robert Alley of the University of Virginia, Jefferson’s creation, makes this extreme statement: “To whatever degree a form of [religious] establishment, no matter how mild, enters the Constitution through the amending process, free exercise of religion is dust.”10 Really? The truth—as former Associate Justice Sandra Day O’Connor continually revealed in her balanced opinions and rulings on the Supreme Court—continues to lie somewhere in between.

The Founders did get it right, as did the rest of the United States of America. Charles Pinckney of South Carolina introduced the “no religious test clause” for public office holding and oath taking in Article VI of the Constitution,11 which directly influenced the outcome of the presidential election of 1800 and the emergence of Thomas Jefferson as president. The constitutional Founders sought an Enlightenment-influenced separation from Puritan and medieval standards of church domination of the state. The religion clauses of the First Amendment set in motion an America that became even more enthusiastically religious, pluralistic, powerful, and free. They empowered the Second Great Awakening.12 As Jon Meacham observed in the PBS special, America emerged in a way like no other country in history—a country in which its citizens could privately and publicly honor its civil-religious traditions without government endorsement or support, financially or otherwise.13

When it comes to government funding, today’s reality may seem to defy the intent of the Founders, but Jefferson’s and Madison’s proverbial “wall of separation” continues to hold back today’s zealous tide of state-sponsored puritanism, while the free exercise of religion continues to hold back the forces of extremism in the form of state-sponsored godlessness.

Ultimately, America’s constitutional Founders believed in freedom of religion, not freedom from religion or freedom to enforce religion on others based on their beliefs, or anyone’s beliefs, particularly acts of worship. This meant upholding both the establishment and free exercise clauses of the First Amendment to a high constitutional standard against powerful forces. Using this standard, government neutrality means that religion and religious institutions must be allowed to thrive freely, but without official endorsement.

The First Amendment, in part, states that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” Today, some seek to reinterpret the no establishment provision separating church and state in ways that would require government to financially support their institutions and enforce their dogmas so as to solve the moral ills of the nation.

Others seek to marginalize the free exercise of religion in favor of placing a higher level of protection on lifestyles destructive to universal moral principles sustaining all societies. Both are harmful to our constitutional health. The nation’s Founders anticipated this tension. That is why they created an internal check and balance within the very wording of the First Amendment in order to prevent the country from being overrun by either extreme in the great church-state debate (a puritanical versus godless society). They believed that if this balancing safeguard were somehow removed by overzealous politicians or the fickle masses, our nation’s constitutional guarantees would be lost, and with it our civil and religious freedoms. As former Associate Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor put it in a speech at the University of Ireland: “The religious zealot and the theocrat frighten us in part because we understand only too well their basic impulse. No less frightening is the totalitarian atheist who aspires to a society in which the exercise of religion has no place.”14

PBS is to be applauded for its special production of First Freedom: The Fight for Religious Liberty. It will help to restore our country’s understanding of its first freedom.

1 See Jon Butler, Awash in a Sea of Faith: Christianizing the American People (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1990). See also Richard L. Bushman, ed., The Great Awakening: Documents on the Revival of Religion, 1740-1745 (Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 1989); and Joseph A. Conforti, Jonathan Edwards, Religious Tradition, and American Culture (Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 1995).

2 See Karen Ordahl Kupperman, ed., Major Problems in American Colonial History: Documents and Essays (Lexington, Mass.: D. C. Heath and Co., 1993).

3 See John Locke, Two Treatises of Government, ed. Peter Laslett (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994).

4 Thomas Jefferson, Writings (New York: The Library of America, 1984), pp. 19-24, final draft version of “A Declaration by the Representatives of the United States of America, in General Congress Assembled.”

5 James Madison, Writings (New York: The Library of America, 1999), p. 10.

6 Saul K. Padover, ed., The Complete Madison: His Basic Writings (Norwalk, Conn.: The Easton Press, 1953), p. 306.

7 Pauline Maier, Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010), p. 444.

8 Letter to Thomas Jefferson, Oct. 17, 1788; in Padover, The Complete Madison, p. 253.

9 First Freedom: The Fight for Religious Liberty (Public Broadcasting System, 2012).

10 Robert S. Alley, Without a Prayer: Religious Expression in Public Schools (New York: Prometheus Books, 1996), p. 56.

11 Philip B. Kurland and Ralph Lerner, eds., The Founders’ Constitution, vol. 4, p. 638. “Mr. Pinckney moved to add to the art:—‘but no religious test shall ever be required as a qualification to any office or public trust under the authority of the U. States.’”

12 See Greg Hamilton, “The Revolution of 1800: Jefferson and the Puritan Assault on the Constitution,” Liberty, March-April 2001, pp. 2-5.

13 See Jon Meacham, American Gospel: God, the Founding Fathers, and the Making of a Nation (New York: Random House, 2006).

14 Sandra Day O’Connor, “Religious Freedom: America’s Quest for Principles,” Northern Ireland Legal Quarterly 48 (1997): 1.

Article Author: Gregory W. Hamilton

Gregory W. Hamilton is President of the Northwest Religious Liberty Association (NRLA). Established in 1906, the Northwest Religious Liberty Association is a non-partisan government relations and legal mediation services program that champions religious freedom and human rights for all people and institutions of faith in the legislative, civic, academic, interfaith and corporate arenas in the states of Alaska, Idaho, Montana, Oregon and Washington. Mr. Hamilton wrote the seminal work, "Sandra Day O'Connor's Judicial Philosophy on the Role of Religion in Public Life," published in 1998 by Baylor University. From time to time, Greg publishes Liberty Express, a journal dedicated to special printed issues of interest on America's constitutional founding, church history and its developmental impact on today's church-state debates, and current constitutional and foreign policy trends. He is available to speak in North America and internationally about these subjects and related issues. To become familiar with the Northwest Religious Liberty Association, please visit www.nrla.com.