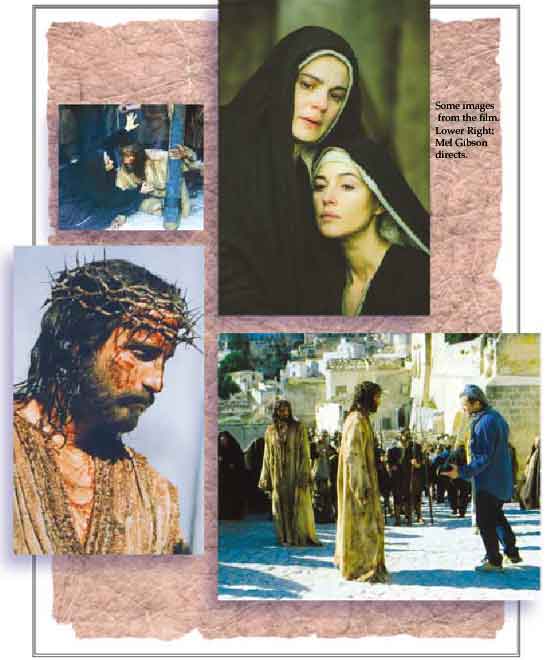

Forbidding Passion

Steven Mosley March/April 2004

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

What is likely the most controversial movie of this year doesn't come with the usual suspects. It doesn't feature some searing inside look at crime or crackheads; it's not about kinky sex or twisted relationships. It's about a 2,000-year-old itinerant rabbi named Jesus.

And yet Mel Gibson, the man behind Passion, and a man with extraordinary Hollywood pull, has had a very difficult time getting his film distributed. No one wanted to touch it for some time—too hot to handle for major studios.

The Passion of the Christ is violent, to be sure. It takes viewers so close to the sufferings of Jesus during His last 12 hours that they almost feel the blood splatter on them. In early screenings many people sobbed unashamedly through much of the movie.

But that's not what almost squelched the project before it could reach theaters. The problem was this: the bad guys were identified. The bad guys were intolerant, oppressive religious leaders. And in this instance they happened to be Jewish. That unleashed a firestorm of indignation—immediately after select audiences previewed a rough cut of the film last summer. It stirred up passions around the world.

Rabbi James Ruden, in the Los Angeles Times, called the movie "radioactive material." The New York Times attacked Gibson's octogenarian father, a man unfortunately given to revisions of history and Holocaust denial. This was offered evidently to prove the apple didn't fall far from the tree.

Writing in Esquire, Kim Masters told readers Gibson would not be able to find a studio to distribute the movie.

The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops weighed in against it, then apologized for attacking a film that is still unreleased.

I asked Paul Lauer, marketing director for The Passion, whether the people behind the film were surprised by the reaction. "Mel expected some degree of controversy," he said, "but the anti-Semitic accusation—that was not at all expected." Mr. Lauer referred to the strong belief in Hollywood that a filmmaker has a right to express his artistic vision. "This is a right that has been battled for fiercely by some of the same people who are trying to keep this film from coming out. It's a very strange twist."

The Anti-Defamation League issued a press release stating that Gibson's film was "replete with objectionable elements that would promote anti-Semitism." What elements? "The unambiguous depiction of Jews as the ones responsible for the suffering and crucifixion of Jesus"; the "exploitation" of "New Testament passages . . . to weave a narrative that does injustice to the Gospels, that oversimplifies history, and that is hostile to Jews and Judaism."

Well, to be sure, anti-Semitism remains a big problem in our world—just as many other brands of bigotry do. And even the Catholic Church has admitted that medieval Passion plays often fueled hatred against Jews by making the Temple priests especially loathsome. So it's certainly legitimate to ask if The Passion follows in that tradition. Does Mel Gibson's movie treat the Jewish characters in this story unfairly? Does it turn them into caricatures?

A few details from the film suggest otherwise.

It's certainly reasonable to assume that there were Jewish higher-ups at the time who spoke out passionately against the irregularities of Jesus' trial. There were figures like Nicodemus who were sympathetic to Jesus. There were voices of moderation like that of Gamaliel who would later, as Acts tells it, counsel his peers to stop harassing the apostles for proclaiming their faith. But the fact is that none of the four Gospels specifically portray anyone in the Sanhedrin walking out in protest at the time of Jesus' trial. That is a dramatic element The Passion adds. And its addition shows Jewish leaders at the time in a more favorable light—not as caricatures.

The ADL has charged: "The film relies on sinister medieval stereotypes, portraying Jews as bloodthirsty, sadistic, and money-hungry enemies of God who lack compassion and humanity."

Yes, The Passion does show Jewish leaders working to get rid of the Man they perceived as their rival and enemy. It shows them offering money to Judas to betray his Master with a kiss. And it shows a Jewish mob before Pilate demanding that Jesus be crucified. None of this is an invention of the movie, of course. All of the Gospels lay out these events in their straightforward narrative.

But the movie shows a very different Jewish population once it moves out into the streets of Jerusalem. As Jesus stumbles along under the burden of His cross, people express sympathy; many are weeping. And in one of the more imaginative scenes in the movie, Jesus'

The movie also has an interesting take on the man Roman soldiers forced to carry Jesus' cross after He collapsed. He is identified in the Gospels as Simon of Cyrene. Cyrene was a city in North Africa, and scholars have debated this individual's ethnic background, some picturing him as a Black man. But in The Passion he is portrayed as a Jew, a man mistreated by the Roman soldiers as a Jew—just as they were abusing the hero of the story as a Jew.

It is the Roman soldiers who are the bloodthirsty sadists of the movie. Their flogging of Jesus is perhaps the most physically wrenching scene ever put on film. When these soldiers drive Him through the streets and Jesus drops under the weight of the cross, the viewer almost feels crushed beneath Him. It is the Romans who coldly pound spikes through His limbs at the place of crucifixion. Gibson heightens the violence of that event by having the soldiers flip the cross over—with Jesus attached to it. They then flatten the ends of the spikes against the wood.

The ADL has protested that The Passion inaccurately portrays "Jews physically abusing Jesus before the crucifixion." Yes, the Temple guards do arrest Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane; there's a scuffle; He's tied up and dragged away. At one point Jesus stumbles off a bridge and must be pulled up by the ropes attached to Him.

This may well be a more violent arrest than anything specifically depicted in the Gospels. But it pales before the gory abuse of the Romans. If any group has cause to worry about being caricatured, it's their descendants. But of course people understand that crucifixion was indeed a gruesome, violent ordeal in the first century. And fortunately most of us have sense enough not to hate the Italians because their imperial ancestors practiced that form of execution.

It seems quite a stretch to paint this movie as anti-Semitic, as something that will ignite hatred and bigotry. The good guys are Jewish. The bad guys are Jewish. The hero is Jewish. What exactly is the problem?

Critics have tried to back up their objections to the movie with claims that it distorts the Gospels. Paula Friedrickson, one of a group of Catholic and Jewish first-century scholars who examined a draft of the screenplay, wrote this: "That script . . . represents neither a true rendition of the Gospel stories nor a historically accurate account of what could have happened in Jerusalem, on Passover, when Pilate was prefect and Caiaphas was high priest."

Quite a claim. Where exactly does the movie go astray? Critics have been pretty sketchy. What the average viewer sees is a rendition of events clearly laid out by Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John.

The movie does take some cinematic liberties. It imagines details here and there to color the story. It even pictures a shadowy, sinister, androgynous figure who pops into this and that scene as an embodiment of evil. But none of these elements do violence to the Gospel narrative.

What the critics come back to, over and over, is the claim that The Passion is historically inaccurate and anti-Semitic because it makes the Jews responsible for Jesus' death.

What the critics come back to, over and over, is the claim that The Passion is historically inaccurate and anti-Semetic because it makes the Jews responsible for Jesus' death.

Well, the fact is that a group of intolerant, oppressive religious leaders of that time did indeed plot against Jesus. Historians seem to agree on that. And those leaders happened to be Jewish. Jewish people sometimes do bad things, just like Brazilians and Mongolians and Swedes sometimes do bad things. But what those who came down hard on The Passion seem to believe is that in order to fight against bigotry, we must never portray Jewish people doing really bad things.

ADL national director Abraham Foxman referred to a Catholic Church pamphlet on combating anti-Semitism and interpreted it to suggest: "Correct Catholic teaching of the passion is one that portrays the Jews accurately, sensitively, and positively." In a letter to Mel Gibson, Foxman maintained: "The church understands that only teachings which promote understanding and reconciliation toward the Jewish people can represent religious truth and the word of God."

Reconciliation and understanding are the best of goals. After all, that was the whole point of Jesus' Passion, according to the New Testament. He died to bring reconciliation and forgiveness to all humanity. But does that mean we should never picture people doing bad things? Is reconciliation dependent on us pretending that particular people or particular groups are sinless? Isn't the opposite true?

Sometimes human beings scream bloody murder. And you just can't portray that in a sensitive, positive light. Sometimes we're cruel. Sometimes we're intolerant. And that's not just a problem for people with certain well-defined prejudices. That's a problem for every individual born on this planet. No one is immune. No one can claim to be without fault because they belong to a victim class. Blacks can be racist. Women can be oppressors. Jews can be intolerant. But what Foxman seems to suggest is that only facts that picture Jewish people doing good things can possibly be "religious truth" or "the word of God."

There is a lot more going on behind the passion against The Passion than a protest against anti-Semitism or historical inaccuracy. The real issue is that Mel Gibson, a practicing Catholic, has expressed religious beliefs that others simply don't agree with. He wanted to convey "the full horror of what Jesus suffered for our redemption." He even told Charisma News: "I hope the film has the power to evangelize. Everyone who worked on this movie was changed."

As a director, Gibson has made the sufferings of Christ more visceral and compelling than any filmmaker in history. Few people will walk away from this movie without being deeply affected. And some will disagree with its content. Many individuals do not believe that Jesus' Passion, played out in Palestine 2,000 years ago, has anything to do with their spiritual well-being or eternal destiny. And an honest and fair response might be to say, "I don't buy the whole atonement thing," or "I just don't see Jesus as the Messiah," or "I think the Gospel writers made a lot of it up."

People have a right to their opinions. In America they have an inalienable right. But what many of The Passion critics have done instead is to claim that Mel Gibson's opinions are out of bounds, that they're so dangerous that they don't belong in the marketplace of ideas. Instead of simply disagreeing, they want to forbid.

As just one example, take this message sent in to the Urban Legends Web site: "I believe in free speech, but not when it fosters hatred and gives our enemies ammunition to perpetuate the greatest crime of the century and the continued persecution of Jews . . . . We will not tolerate this additional insult."

Gibson's movie does identify some bad guys in the story. But the truth is that according to Gibson's own faith, we're all the bad guys. We're all complicit in the death of Christ as human beings desperately in need of God's pardon. That matters infinitely more than who happened to be among the heavies as the drama of the atonement played out.

What Gibson hopes to accomplish is to "inspire, not offend. . . to create a lasting work of art and engender serious thought among audiences of diverse faith backgrounds."

According to Paul Lauer, that has already started to happen. He told me about an early screening in Houston attended by a very eclectic mix of rabbis, priests, and ministers. "In follow-up meetings," Lauer said, "there was a tremendous amount of discussion and debate. Even though there are different ways people receive the film, the dialogue it has generated has been extremely positive for that community, for these different bodies of believers."

In many other places, however, the passions aroused by The Passion have shown how easily it is to fracture the ideal of religious liberty and freedom of expression. If this movie can be branded as something evil that fosters hatred and persecution, imagine what else may be forbidden; imagine how narrowly the politically correct may choose to define what is "sensitive and positive" communication.

We've come a long way from the wisdom of Gamaliel, who, in advising his less-tolerant colleagues to leave the apostles alone, said in effect: "If this is of human origin, it will fail. If it's from God, you won't be able to stop it" (Acts 5:38, 39, paraphrased).

________________________

Steven Mosley, an author and television producer, livers in Westlake Village, California. His latest book is Secrets of Jesus' Touch.

________________________