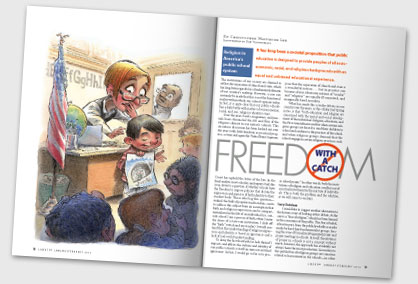

Freedom With a Catch

Christopher Whitmore Lee January/February 2012

It has long been a societal proposition that public education is designed to provide peoples of all socioeconomic, racial, and religious backgrounds with an equal and unbiased educational experience.

The institutions of our society are claimed to reflect the separation of church and state, which has long been regarded as a fundamental element of our country's makeup. However, a case can certainly be made that this is not the functional reality within which our schools operate today. In fact, it is quite clear that our public schools face a daily battle with matters of socioeconomic, racial, and, yes, religious identity issues.

Over the years books, magazines, and journals have chronicled the ebb and flow of the religious climate in our nation's schools. This circuitous discussion has been hashed out over the years with little headway or practical progress, as time and again the United States Supreme Court has upheld the letter of the law. In the final analysis most scholars and experts boil this issue down to a question of whether schools have the freedom to impose policies that dictate the expression and exercise of faith identity to their student body. Those who beg this question—indeed, the bulk of popular media today—seem to address this subject from an assumption that faith and religious expression can be compartmentalized in the life of an individual (i.e., outside school I am a person of faith; when I enter the doors of a state-run institution, I click off the "faith" switch and am secular). I would contend that this understanding of religious expression and identity is based in ignorance and a lack of real-world understanding.

To deny the fact that faith (or lack thereof) impacts and affects the culture and identity of our public schools is itself an exercise in blind ignorance. In fact, I would go so far as to propose that the separation of church and state is a wonderful notion . . . but in practice can become a farce. Moreover, notions of "secular" and "religious" are equally ill-conceived, and marginally based in reality.

What has made this a tricky debate in our country over the years, as the scholar Joel Spring notes, is that "both education and religion are concerned with the moral and social development of the individual. Religion, education, and the First Amendment conflict when certain religious groups are forced to send their children to school and conform to the practices of the school, and when religious groups demand that the schools engage in certain religious practices, such as school prayer." In other words, both the institutions of religion and education conflict out of a mutual investment in the nurture of individuals. This is both the problem and the solution, as we will come to see later.

Scary Christians

I would like to suggest another alternative to the historic ways of looking at this debate. At the core is a "fear of religion," which has been formed in the conscience of the public. This fear is fueled, at least in part, from the publicly volatile crusades made by hard-line fundamentalist groups, forcing the issue of formalized/organized prayer and prayer meetings in schools. In itself, the existence of prayer in schools is not a concept without merit; however, the approach has evidently not always been the most productive. Secondary to this public fear of religious groups are concerns related to harassment in the schools—in other words, one child condemning, antagonizing, or discriminating against another with regard to religious differences. The traditional way we have sought to address these dynamics has been to "take it to court." The result has been that the United States judicial system has ruled objectively, as only it may, according to an interpretation of the law. As humanity as a whole seems to be inclined to do, we continually frame prayer in schools, religion/education, church/state issues in black-and-white terms, setting up an antagonistic battleground. Children have their free-exercise rights protected but exist in a school environment strangely aloof from that important part of their lives. When young Johnny draws an Easter scene in art class and proudly wants to show it to others and talk about it, the teacher and administrators collectively grimace with the awkwardness of how to respond to the child. Unfortunately, more often than not, school officials respond from a place of fear (as they must to cover themselves). The result is that faith and religion are treated like the drunken uncle who never gets mentioned at family get-togethers; they are taboos with no place at school and, therefore, life as well.

Perhaps this is why the debate has dragged on for so long with little positive headway. As a society, we are trying to solve a dispute objectively, which fundamentally has to do with beliefs, perceptions, and fears—subjective issues. National, state, and school officials are promoting a policy of "religion-free zones" at schools, seeking to address the matter as an issue of constitutional law, rather than adopting a more wholistic perspective, and taking into account cultural, psychological, and political elements. Perhaps our course as teachers, school administrators, and district and state officials should be to seek the creation of a climate that affirms the validity and purpose of faith in the lives of individuals and communities, and that gives validation to the value of religious identity and expression.

Are our public schools truly institutions set apart from matters of faith and religion? How do "religion phobia," harassment, a litigious society, and ignorance contribute to the issue? Now more than ever we are in dire need of a platform where faith traditions/differences can be discussed openly, as an important component of our individual and societal framework; without this platform we are, in essence, teaching our children that faith has no place or value in our lives. It is a taboo, mystical element of our experience that should be hidden away, brought out only for the appropriate occasions—an extremely unhealthy dynamic. We are creating a generation of closet people of faith, sabotaging the purpose for creating "equal-opportunity schools," and creating instead an oxymoron.

Religion Phobia and the Fear of Harassment

Religious freedom? Prayer in school: right or wrong? Maybe we're asking the wrong questions. In their wisdom our forebears sought to define a principle that would achieve balance and unity among the people of the United States of America. From this quest a First Amendment was forged. Could they have fathomed how the words stated in that one amendment would be defined and redefined, upheld, appealed, and overturned, hashed out and hair-split? After years seeking to come up with a definitive position to solve issues of church/state balance, I wonder if we have spent in excess of 200 years asking the wrong question. The question is indeed a "how" question, not a "who is right, who is wrong" question. The real issues that must be addressed are how to cope with a fear of diversity (and inherently, religious diversity), and maintaining the integrity of one's religious identity and beliefs in the school arena. The answer here, I believe, is really quite simple: schools need to adopt a policy that is something close to what the author Paul Blanchard coined "friendly neutrality," but to take it a step further. Schools need to adopt—as part of their mission clauses that promote the acknowledgment and acceptance of religious and spiritual identity as a valid and core component of healthy human development—a policy of religious tolerance and support.

For too long what we have sought to do as a nation is run away from or avoid the reality that religion and our identity as a nation are intimately intertwined. We have sought, instead, to separate these two entities rather than embrace their oneness. We have given lip service to "protecting the religious freedoms of this country," when truly the goal has been to protect people from religion as it has been fleshed out on public school campuses across the country. The state of our nation at the current time is one of religious intolerance, almost the reverse of what it was when the framers drew up our Constitution in the 1700s.

This intolerance has been exacerbated by the vehement push of extreme religious lobbying groups using force and scare tactics to promote their agenda for "allowing prayer in schools," as if prayer can be accomplished only when organized and officially pronounced. As the extreme Religious Right has pushed the "school prayer" matter into media attention, the collective national response has been repulsion; and what has been promoted is increasing anger and further divisiveness instead of engendering support and appreciation for people of faith to express themselves openly in all venues of life.

Evidence of the nation's growing split was seen in the Supreme Court's rejection of an appeal supported by Alabama governor Fob James on June 22, 1998. James made school prayer his own personal election platform and, in his most embarrassing display, used it to point a finger of blame at the U.S. Supreme Court judges.

The result of the governor's caustic approach to getting his agenda across was a court rejection that barred teacher-led devotionals and vocal prayer at assemblies. What the ruling displayed was the gradual disintegration of tolerance for expression of religious identity in our schools, fueled by the inflammatory statements of an abrasive and vocal minority. Vocal prayer and devotionals could be used as tools to bring about greater unity and understanding across faith lines and in the midst of school community. Instead, they have become fodder for anger and hate. This is the truly unfortunate aspect of the current trend in the religion/schools dialogue: that all religious bodies are defamed on account of the stupidity of a vocal minutia.

Now we hear of people bringing cases to our courts citing "religious harassment" in schools; one person "infringes upon the rights of another" by openly expressing their religious identity. Supposedly this is happening even at the elementary school level, where children don't even know who they are yet, let alone how to spell their name or remember a street address. Is it religious harassment that is truly being experienced? Or rather, could the root stem from a lack of knowledge about diverse religious traditions that make up our society? And if it truly is harassment, how do we define it?

Time and again, when talking about the matter of dealing with religion in our schools, we come back to the question of definition. Time and again, the traditional solution to the issue provides no helpful answer.

Toward a Common Ground

What we need now are school classes and policies that seek to educate students about another kind of tolerance: religious tolerance. What is needed is, ironically, more education! With increased understanding and wisdom, perhaps fewer cases will make their way to the Supreme Court's docket. Unfortunately, this brand of a prevention strategy is not likely to occur anytime soon. We have become very good over the past 200 years at being reactionaries; avoid the conflict, ignore it, control it. One who is engaged in a prevention approach to questions of faith expression and education sees the promise and possibility in action: have principals and school officials support assemblies in which the theme is sharing a variety of religious histories and perspectives complete with explanation of ceremonial dress, and information about beliefs and traditions. Provide avenues for discussion groups to talk about faith/religious difference in an intentional format during school hours, and study groups after school hours for those interested who want to discuss in more depth. We have assemblies for better dental hygiene and stopping drug abuse, so why are we so afraid to talk about religious diversity and the importance of understanding others?

As an educator in the Florida public schools and an ordained Lutheran pastor, I will witness to the fact that all too many school principals and officials now avoid the subject of religion like the plague. Nobody wants to touch it when the subject of religion rears its head in the educational arena. Ultimately, those who suffer will not be the administrators, teachers, or elected officials who get sued and taken to court—it will be the kids.

With luck (or help from God—depending upon your religious convictions), perhaps, we will one day soon see that the key to the "should religion be in schools" debate has nothing to do with whether or not it should exist, but rather, how we, as children of God, will become better students of understanding and acceptance ourselves.