Gallileo in Reverse

Jonathan Gallagher May/June 2006

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

When Pennsylvania Judge John Jones wrote his opinion that "ID [intelligent design] is not science" in the case of Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District (December 20, 2005), all sides of the argument grabbed his words for their cause.

To those keen to maintain the "scientific integrity" of the evolutionary argument, this was indeed good grist for the mill. Here was a judge concluding that the only acceptable definition of science was evolution-based, they said.

On the other side, activists pointed to the strange spectacle of a nonscientist defining science. How was it, they wondered, that scientists needed case law to bolster their position? Was this not a case illustrative of legal dogmatism rather than the supposed openness of scientific quest?

Add to the mix the issue of separation of church and state regarding intelligent design ideas (one argument that to many seemed a stretch too far); the moral conclusions that are inevitably dependent on origin perspectives; and the continuing battle for the minds of the young and innocent, and it's no wonder that this verdict has brought an avalanche of varied observations.

Yet in all the infighting, it's tragic that the essential freedom of belief and the right to choose seem lost. Those on each side are so sure of the correctness of their respective positions that this is the point of debate, and not the opportunity to calmly and reasonably examine the evidence before making one's decision.

Dictating the Meaning of Science

Take another look at Judge Jones's affirmations regarding science. First, what it is not:

The esteemed judge surely makes a historical error in point 1. Newton, while establishing his laws of motion, was also writing a commentary on the book of Revelation. He saw no contradiction between natural laws and the supernatural actions of the Creator. Similarly, many scientists over the centuries have not dismissed supernatural causation in such a cavalier manner as did Judge Jones.

For Newton, his investigations were "thinking God's thoughts after him." More recently no less a scientist than Einstein wrote, "I want to know how God created this world. I am not interested in this or that phenomenon, in the spectrum of this or that element. I want to know His thoughts; the rest are details."

It all depends on the definition of science, as we shall see later. For the moment, let us simply observe that the "centuries-old ground rules of science" do not speak in either religious or secular terms. Scientific methods relate to observable facts and determinations. It is in the realm of interpretation that concepts differ.

The judge's out-of-hand dismissal of irreducible complexity in point 2 is more an illustration of a belief position than a reasoned examination of the evidence. His comments sound more like a prejudged opinion than a desire for openness to differing ways of reading the evidence, as is required by scientific inquiry.

Similarly the assertion in point 3 that the attacks on evolution have been refuted by the scientific community is such a broad generalization that it is unacceptable. (Who agrees that refutation has occurred? Who decides on the standard for refutation? By whose interpretation of the evidence has the concept been refuted? Etc.) Even if such an assertion were true, does this mean that the debate on the question of origins must then be silenced and only one view advanced?

What Is Science? Who Decides?

The judge goes further in his delineation of what science means: "This self-imposed convention of science, which limits inquiry to testable, natural explanations about the natural world, is referred to by philosophers as 'methodological naturalism' and is sometimes known as the scientific method. . . . Methodological naturalism is a 'ground rule' of science today which requires scientists to seek explanations in the world around us based upon what we can observe, test, replicate, and verify."

He continues: "NAS [National Academy of Sciences] is in agreement that science is limited to empirical, observable and ultimately testable data: 'Science is a particular way of knowing about the world. In science, explanations are restricted to those that can be inferred from the confirmable data—the results obtained through observations and experiments that can be substantiated by other scientists. Anything that can be observed or measured is amenable to scientific investigation. Explanations that cannot be based upon empirical evidence are not part of science.'. . . This rigorous attachment to 'natural' explanations is an essential attribute to science by definition and by convention."

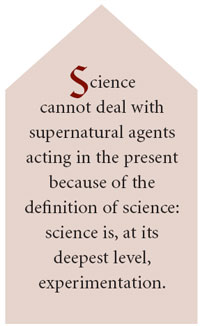

All well and good. In the words of the famous scientist Lord Kelvin: "Science is measurement." The problem at issue is, however, not over scientific methodology or measurement, but over how scientific facts are understood and interpreted. When it comes to concepts and mechanisms of origins, science as so precisely defined by Judge Jones totally fails. There is no possibility for measurement or observation, since it is a past event. It cannot be reproduced. It cannot be studied in a laboratory. So by very definition, all theories about origins are just that—theories. They cannot be established by science. Scientific facts noted in the current universe may lead to some postulations as to what occurred, but these are based on inference, not on scientific methodology of observation, hypothesis, experiment, and demonstration.

"Science cannot deal with supernatural agents acting in the present because of the definition of science: science is, at its deepest level, experimentation. We cannot experiment on a supernatural process; neither can we experiment on the past. Only the present and the physical processes currently at work are testable.. . . Thus, by definition, intelligent design is not science, because the act of design no longer occurs and is not testable. But the theory of evolution is not science either" (student Jake Morris commenting on the Kitzmiller decision in the York Daily Record).

Directly contradicting such an observation is this from the University of California at Berkeley's Web site: "Evolution is observable and testable. The misconception here is that science is limited to controlled experiments that are conducted in laboratories by people in white lab coats.

Actually, much of science is accomplished by gathering evidence from the real world and inferring how things work. Astronomers cannot hold stars in their hands and geologists cannot go back in time, but in both cases scientists can learn a great deal by using multiple lines of evidence to make valid and useful inferences about their objects of study." (As an aside, perhaps the most interesting aspect of this piece of dogmatic assertion is the use of the words "inferring" and "inference.")

In a World Peace Herald piece, Lloyd Eby, a lecturer at George Washington University with a doctorate in the philosophy of science, blasts the judge in seeking to define science, and then extrapolate to denying anything other than natural causation:

"Judge Jones went beyond both his competence and the proper bounds of his office when he propounded an answer—and a tendentious one at that—to the question, 'What is science?' and then went on to declare that science must be restricted to methodological naturalism. . . . But many people, among them a lot of today's proponents of neo-Darwinist evolution, move from the scientific stance of methodological naturalism to metaphysical naturalism. In other words they make a leap—a leap that is not supported by either good logic or good observation—from a method of science in which only natural explanations are to be accepted as scientific, to a declaration that only natural phenomena exist and that all natural phenomena can be explained without reference to extra natural (supernatural) phenomena and existence(s). . . . Thus, in the stance of many of its proponents, Darwinian and neo-Darwinian evolution frequently becomes a semi-religious view because it is given as a support for the view that no supernatural reality exists, and because it is offered as an answer to the question of 'ultimate things.' Such answers are, by their nature, at least semi-religious if not fully so."

But the judge claims, on the basis of this trial, to represent the best authority: "After a six week trial that spanned twenty-one days and included countless hours of detailed expert witness presentations, the Court is confident that no other tribunal in the United States is in a better position than are we to traipse into this controversial area."

Free Expression?

The real issue here is openness. If different theories about origins cannot be discussed in the classroom, then where? The goal of education is to provide not just information—the factual evidence—but also mechanisms for interpreting evidence. Questioning, examining, analyzing—all these are essential tools. But if scientific dogmatism is allowed to close the door to alternatives, then it is not surprising that there is a negative reaction. The idea that "science" always provides the answer is increasingly difficult to maintain in a world plagued by some of the results of scientific and technological "developments," and it demeans good science if some are allowed to dictate one particular view on any subject.

It is interesting that the case of Galileo and his treatment by the church is often used as an example of overreaching dogmatism. Certainly in the end Galileo was proved right, not through dogmatic assertion, but through the demonstration of the truth of his observations—this despite the persecuting power of the church that branded him and his views heretical. Indeed Cardinal Bellarmine, judge at Galileo's "trial," affirmed that "to assert that the earth revolves around the sun is as erroneous as to claim that Jesus was not born of a virgin."

But now the dogmatic boot is on the other foot. Judge Jones has ordered that intelligent design not be referred to as an alternative theory of origins in the classrooms of the Dover School District. The Skeptic's Society trumpeted the verdict as "Not Intelligent, Surely Not Science." Even the American Institute of Physics issued a news bulletin with the headline "Judge Concludes Intelligent Design Should Not Be Taught as Science."

Instead of wondering what a judge is doing in defining science, it seems that such defenders of dogmatism in the scientific community are only too happy for a legal "No Trespassing" fence that prevents entrance and discussion by those of differing views.

The most disturbing aspect of the whole debate is that under the guise of supposed church-state separation issues, the opportunity for investigation and debate about origins is chilled. Required academic uniformity is enforced, and good learning goes out the window. Instead of a healthy debate in a respectful environment we have the imposition of thought control more in keeping with Orwell's 1984. Whatever happened to freedom of thought and expression?

In the end it was one Galileo Galilei who concluded, "I do not feel obliged to believe that the same God who has endowed us with sense, reason, and intellect has intended us to forgo their use." Wise words for our times too.

Jonathan Gallagher holds a bachelor's in applied chemistry from Portsmouth University, England, and a Doctor of Philosophy degree from the University of St. Andrews in Scotland. After working as a scientist in the European space industry, and as an ordained minister, he currently represents the Seventh-day Adventist Church to the United Nations.

1 Available at www.pamd.uscourts.gov/kitzmiller/kitzmiller_342.pdf.

2 Ibid., p. 64.

3 Ibid., p. 66.

4 York Daily Record, Dec. 25, 2005.

5 evolution.berkeley.edu/evolibrary/misconceptions_faq.php#b6.

6 World Peace Herald, Jan. 5, 2006.

7 Kitzmiller, p. 63.

8 FYI, #177, Dec. 26, 2005.