General Orders No. 11

Clifford R. Goldstein January/February 2024General Orders No. 11 “The Jews, as a class . . . are hereby expelled.”

It’s a case of history being, typically, historical. A time of crisis, even war. Economic uncertainty making matters worse, threatening perhaps the fate of the nation. People needing to blame someone smaller, weaker, and unable to defend themselves. Like the Jews.

Hence, General Orders No. 11: “The Jews, as a class, violating every regulation of trade . . . are hereby expelled from the department. Within 24 hours from the receipt of this order by post commanders, they will see that all of this class of people be furnished passes and required to leave, and anyone returning after such notification will be arrested and held in confinement until an opportunity occurs of sending them out as prisoners, unless furnished with permit from headquarters.”1

When and where was this order expelling the Jews, “this class of people”? Czarist Russia? Medieval Spain? Early Nazi Germany?

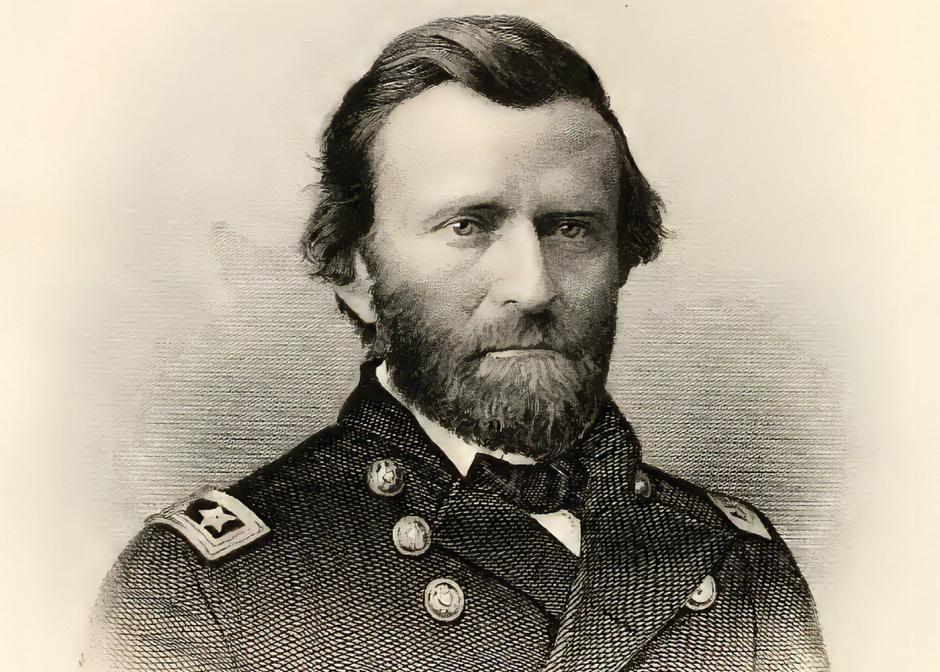

No. The United States of America, in the middle of the nineteenth century—1862, to be precise. And the man who issued “what is today considered to be the most anti-Semitic military proclamation ever enacted in United States history”2 was Major General Ulysses S. Grant, who went on to become the commanding general of the United States Army, acting United States secretary of war, and the eighteenth president of the United States of America.

How could something like this happen in, of all places, the United States, only 71 years after the ratification of the Bill of Rights? But, more important, what can we now, more than 230 years after ratification, learn from this unfortunate incident?

The Black Flag

For most Americans north of the Mason-Dixon line or west of the Mississippi River, the Civil War is about as far from their consciousness as is the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta, in the late fifth century B.C. Yet it ravaged the nation, with effects still felt today. Few now comprehend the hatred it stoked on both sides; a hatred perhaps best expressed by Confederate General Stonewall Jackson’s infamous black flag statement, in which he said to Colonel J. E. B. Stuart that we might have “to show no quarter to the enemy. No more than the redskins showed your troopers. The black flag, sir.” 3 It meant, basically, take no prisoners alive. Fortunately, things never got that bad.

But things still got bad enough. One of the worst battles in American history was at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, in July 1863, with an estimated 7,100 dead. Americans killing Americans. Before the carnage of the war ended, the estimated dead on both sides was about 620,000, making it by far the deadliest war in American history. It takes a lot of hate to kill that many of your own countrymen.

The Cotton Situation

It was in this context, and against this foreboding background, that Ulysses S. Grant, then a major general in the Union army, comes into play. In 1862 the war itself had not been going well in general for the Union or, in particular, for General Grant. He found himself under heavy criticism for his failure, so far at least, to take the Confederate stronghold of Vicksburg, Mississippi, which was crucial to the Union’s war effort. Deep in enemy territory, “ringed by danger,”4 and isolated from General William Tecumseh Sherman’s army, which was up farther north and unable to help, Grant and his men sorely lacked supplies and reinforcements. Worse, wrote Seth Reid Clare,“Grant found himself plagued by Confederate cavalry led by Nathan Bedford Forrest and Earl Van Dorn, who perpetually harassed Grant’s troops without ever making themselves available for all-out combat.”5

What brought issues to a head, however, was the cotton situation. With his army deep in Confederate cotton country, Grant had to deal with northern speculators, corrupt Union army officers, and (as he and others saw it), “Jews,” all of whom were trying to take advantage of the astounding surge in cotton prices, which had risen from 10 cents a bale to $2.00 because of the war. With the Union’s dire need of cotton, unscrupulous traders from the North were able to get around strict regulations about the purchase of Southern cotton (which put money in the enemy’s coffers) and made great profit selling it to the Union army. Grant harbored deep animosity toward war profiteers of any kind. But, because some of these profiteers were Jewish—a tiny minority, actually—the Jews, often immigrants heavy laden with accents, were the easiest to stigmatize.

Thus, on December 17, 1862, Grant issued the General Orders No. 11, which meant the expulsion of the Jews “as a class” from much of Tennessee, Mississippi, and Kentucky —even if the vast majority of that “class” were not involved in cotton speculation at all. Despite protests from his own ranks, and being warned that Washington would countermand it, Grant insisted that the order be issued and enforced.

And it was enforced, at least in part. Jews living in Holly Springs, Mississippi, Grant’s main supply depot, were immediately rounded up and forced out, some having to travel 40 miles on foot. Soon after the order, a Confederate army raided the area, breaking Union communication lines, and so many local Jews were spared.

“Luckily,” wrote a Grant biographer, Ron Chernow, “during the brief time Grant’s obnoxious directive was in effect, it was weakly enforced. The sole exception came in Paducah, Kentucky, where thirty Jewish families received notice to leave the city within twenty-four hours. These shell-shocked Jews hastily collected their belongings, shuttered their homes and shops, and boarded an Ohio River steamer.”6

Shell-shocked Jews told to leave right away, shuttering their homes and shops, and then deported? Switch out “Ohio River steamer” for the Deutsche Reichsbahn, and one would think they were reading about the Holocaust, not about a military order issued within the United States itself.

Regrets and Redemption

Though most Jews would consider Grant’s order irresponsible and wrong, compared to what they could have faced, and often did in Europe, what happened here was small potatoes. And the outrage against the order, both by Jews and non-Jews, was swift and fierce. In the U.S. Senate a resolution calling the order “tyrannical, usurping and unjust”7 was presented but not passed. Many thought it better to let President Lincoln handle it, which he did, immediately directing General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck to make Grant revoke the order. Grant complied.

For years afterward, Ulysses Grant seemed to regret General Orders No. 11. He issued an apology, of sorts, in an 1868 letter to Jewish Congressman Isaac N. Morris that was later published in newspapers nationwide: “I do not pretend to sustain the order,” he wrote. “The order was made and sent out, without any reflection, and without thinking of the Jews as a sect or race to themselves, but simply as persons who had successfully . . . violated an order.” Grant also stressed, “I have no prejudice against sect or race, but want each individual to be judged by his own merit. General Orders No. 11 does not sustain this statement, I admit, but then I do not sustain that order.”8 In his famous two-volume autobiography, The Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant, he never mentioned it, his silence being interpreted as shame.

Fascinatingly enough, one of his first acts as president was to appoint a Jew, Simon Wolf, as the recorder of deeds. Grant went on to put more Jews to government positions than any other president had so far, and also responded forcefully to the Russian expulsion of Jews from its border—an act for which, politics being politics, brought him some scorn. He also became the first American president to attend the dedication of a synagogue, Washington’s Adas Israel.

In an article titled “The Redemption of Ulysses S. Grant,” Jonathan Sarna of Brandeis University wrote: “The Grant years had brought American Jews heightened visibility and new levels of respect. More Jews served in public office than ever before. . . . During his administration, American Jews moved from outsider to insider status, and from weakness to strength. After having abruptly expelled Jews in 1862, Grant as president significantly empowered them—insisting, over the objections of those who propounded narrower visions of America, that the country could embrace people of different races, religions, and creeds.”9

Whatever his motives, Grant, it seems, learned from his mistake.

The Prevailing Cultural Prejudice

Besides the obvious lesson here, about how in times of crisis human rights are always threatened, even despite protections like the long-ratified Bill of Rights—something else is worth considering. Perhaps the scariest aspect of what was deemed “the most anti-Semitic military proclamation ever enacted in United States history” is that it was not enacted by an overt anti-Semite. Little indicated that General Grant was anti-Semitic, at least any more than anyone else at that time. He was simply caught up in the tensions of the moment, and based on the prevailing cultural prejudice—what could be called a “sloppy” anti-Semitism—Grant responded in ways that were, obviously, wrong.

Almost everyone has heard of the Stanford Prison Experiment. In a simulated prison, role-playing “guards” (male students recruited through a newspaper ad) became so cruel to “prisoners,” and so quickly, that the experiment had to be called off. Though the study has been criticized, who needs an experiment to know the potential of human evil? Many Holocaust perpetrators were not overt anti-Semites either. Caught up in the prevailing prejudices of the times, they did things that, in different circumstances, would have horrified them.

Meanwhile, who hasn’t, under pressure, done what they otherwise wouldn’t do? This problem becomes bigger when those under that pressure have power, as did Major General Grant. Good people can do bad things, especially in an environment that either subtly or overtly allows, sanctions, or encourages it. What the story of Ulysses S. Grant and General Orders No. 11 shows, then, is that no one is secure from these cultural prejudices, no matter how egregious; and, if pushed hard enough, anyone can succumb to them, often to the detriment of those at their mercy.

Clifford Goldstein is a former editor of Liberty magazine and the current editor of Bible study lessons for the Seventh-day Adventist Church. He has an M.A. in Ancient Northwest Semitic Languages from Johns Hopkins University and is the author of more than 20 books, the most recent being God, Godel, and Grace (Review and Herald) and Graffiti in the Holy of Holies (Pacific Press).

1 General Orders No. 11. Headquarters, 13th Army Corps, Department of the Tennessee: Oxford, Miss., Dec. 17, 1862.

2 Seth Reid Clare, “General Grant’s Order 11: Causes and Context.” Chrestomathy: Annual Review of Undergraduate Research 11 (2012): 34.

3 S. C. Gwynne, Rebel Yell: The Violence, Passion, and Redemption of Stonewall Jackson (New York: Scribner, 2015).

4 Ron Chernow, Grant (New York: Penguin Press, 2017), Kindle Edition, p. 232.

5 Gwynne, Rebel Yell, p. 25.

6 Chernow, Grant, pp. 235, 236.

7 Seth Kaller, “Grant’s Infamous General Order 11 Expelling Jews—and Lincoln’s Revocation of it,” retrieved from sethkaller.com.

8 Quoted in “Ulysses S. Grant and General Orders No. 11,” retrieved from the Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site section of www.nps.gov.

9 Jonathan D. Sarna, “The Redemption of Ulysses S. Grant,” retrieved from www.reformjudaism.org.

Article Author: Clifford R. Goldstein

Clifford Goldstein writes from Ooltewah, Tennessee. A previous editor of Liberty, he now edits Bible study lessons for the Seventh-day Adventist Church.