How Religious was my Tax Exemption

Lee Boothby July/August 2003

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Illustrations by John MacDonald

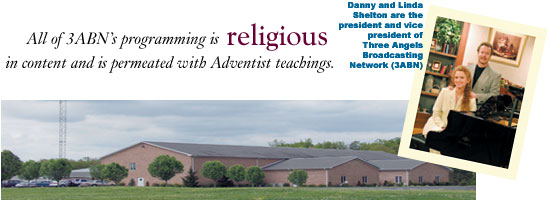

Three Angels Broadcasting Network is the realized dream of Danny Shelton and his wife, Linda. Today 3ABN, as it is known, is a 24-hour Christian television/satellite and radio network that began in 1984 when Danny was impressed to build a religious television station that would reach the world. From Thompsonville, Illinois, its ministry now reaches across North, Central, and South America, Europe, the Middle East, Africa, Asia, and Australia.

During the small hours of that November 1984 morning, a sleepless Danny Shelton was impressed to start a television network to serve his faith. But a more unlikely candidate than this Seventh-day Adventist layperson would be difficult to find. With only a high school education he was a carpenter who had neither money nor property.

Today 3ABN operates a religious television network and is active in other evangelistic and missionary activities. Not only does it maintain a pastoral staff on site, but its evangelistic team is involved in direct evangelism resulting in many baptisms, including 15,000 in India and similar numbers in Russia in recent years.

Even though all of 3ABN's programming is religious and designed to be consistent with the teachings of the Adventist Church, the Illinois Department of Revenue and the elementary and high school districts (Thompsonville Community High School District No. 112 and Thompsonville School District No. 62) now claim that because it is a television facility, its operation is secular. So 3ABN is in a legal challenge with the Illinois taxing authorities, the ultimate outcome of which may well have a major impact on religious ministries not only in Illinois but across the country. But Danny and Linda Shelton, the 3ABN staff, and its millions of viewers all believe God is on their side and will make the difference in their struggle against state and local governmental authorities.

All 50 states and the federal government provide tax exemptions for charitable organizations, including churches. The United States Supreme Court has observed that "few concepts are more deeply embedded in the fabric of our national life, beginning with pre-Revolutionary colonial times, than for the government to exercise at the very least this kind of benevolent neutrality toward churches and religious exercise generally so long as none was favored over others and none suffered interference."1 But the Illinois Department of Revenue both attempts to limit the plain wording of the exemption statute and ignores its constitutional obligation of religious neutrality.

The Illinois Revenue Code exempts "all property used exclusively for religious purposes . . . and not leased or otherwise used with a view to a profit."2 One early Illinois court decision interpreted the exemption statute's "religious purpose" proviso as limited to "public worship, Sunday schools, and religious instruction."3

But later decisions broadened the definition of "religious purpose." One decision exempted the administrative and office buildings of a publishing house printing and distributing religious books and materials.4 In another case the court held that an organization established to organize Christian student groups, which also published religious literature, was engaged in a religious purpose under the exemption statute.5 A later court decision held that an organization formed by various Christian schools to produce print, audio visual, and other materials to train Christian educators was entitled to a tax exemption.6 But in spite of these other cases, the Illinois Department of Revenue and school districts argue that any exemption should be restricted to religious worship.

Shortly after its incorporation 3ABN was granted by the United States Internal Revenue Service a 501(c)(3) tax exemption as a not-for-profit religious and charitable organization. It was even given a sales tax exemption by the Illinois Department of Revenue, the same state agency that has denied its claim to real property tax exemption.

In October of 2000 the Thompsonville school board, the mayor of the village of Thompsonville, and members of the Thompsonville Village Council requested that the Franklin County, Illinois, Board of Review deny 3ABN's claim for tax exemption. Particularly curious is the motivation of the village of Thompsonville to object to 3ABN's tax exemption status. The 3ABN property in question is not even located in the village. Although 3ABN does own a couple of parcels within the village, property taxes have always been paid on those parcels of land.

Three Angels Broadcasting has installed its own water and sewer system, maintains its own lighting, and has paid to Franklin County several thousands of dollars through the years to oil and chip county roads adjacent to 3ABN properties. The network has paid nearly 0,000 in property taxes over the past five years on real estate it owns but does not claim a tax exemption for.

According to 3ABN, the taxing units urging denial of its tax-exempt status are shortsighted. With more than 100 3ABN employees living in the county, it is estimated that the 3ABN payroll brings in more than million a year in revenue to the community. In addition, the property acquired by 3ABN has had the effect of raising the tax base on other properties in the area.

Some think if 3ABN were owned and operated by one of the church groups representing a larger segment of the Franklin County community, there would be no objection to its religious tax exemption. But the County Board of Review disregarded the logic and apparent, clear wording of the state law providing real property tax exemption for organizations organized and operated for religious purposes. And the Illinois Department of Revenue denied 3ABN's claim to a real property tax exemption.

This return to a very restrictive application of the Illinois religious exemption provision could very well be the result of a recent budget crunch being experienced in Illinois as well as in other state and local governments coast to coast. It is no secret that almost all states, municipalities, and school districts are finding themselves with a severe deficit in their coffers as a result of an economic downturn.

Tax-exempt nonprofit organizations provide a tempting possibility for additional tax resources.

Both state and local governments have attempted to increase revenues by reducing tax exemptions for churches. Proposed legislation in Colorado seeks to make it easier for the state to challenge an organization's religious mission and purpose, on which a tax exemption claim is based.7

A recent ballot referendum in Colorado sought to eliminate any property tax exemption for real property used for religious purposes. It was argued that fairness dictates that everyone who uses public services should share the cost of paying for such services. Also, supporters argued that the separation of church and state requires the elimination of tax exemptions for churches.8

Opponents of the ballot issue argued that if the tax exemption were eliminated, people who donate to churches would be indirectly taxed, because their donations would be diverted from providing for the religious ministry to paying property taxes to the state. It was also claimed that it could lead to excessive church-state entanglement by the state in religious activities.

In at least three other states having property tax exemption provisions similar to those in Illinois, taxing authorities have challenged the right of television ministries to qualify as a religious or church use. In Minnesota9 and Texas10 courts have ruled that property associated with the furtherance and support of such ministries is tax-exempt. A lawsuit was also filed by a Christian ministry, Good Friends, Inc., of Avondale, in 2002 that charged that the Arizona Department of Revenue acted improperly when it refused to grant tax-exempt status to the television and production facilities owned by that television ministry. The dispute was resolved when the taxes were refunded.11

In a landmark 1970 decision, Walz v. Tax Commission of New York City,12 the Supreme Court held that a New York State statute that included an exemption from real property taxes by associations organized and used exclusively for religious purposes did not violate the First Amendment's establishment clause. Under the New York tax exemption statute religious organizations were included among a broad group of charitable organizations.

The Walz decision observed that "government grants exemptions to religious organizations because they contribute to the pluralism of American society by their religious activities."13 The Court stated that "government may properly include religious institutions among the variety of private, nonprofit groups that receive tax exemptions, for each group contributes to the diversity of association, viewpoint, and enterprise essential to a vigorous pluralistic society."14

Former Justice William Brennan, who consistently championed the principle of church-state separation, agreed that the statute did not violate the First Amendment. He stated that "by diverting funds otherwise available for religion or public service purposes to the support of the government, taxation would necessarily affect the extent of church support for the enterprises that they now promote. . . . In short, the cessation of exemptions would have a significant impact on religious organizations."15

At the beginning the challenge to 3ABN's claim to tax exemption was that the Department of Revenue now and the courts later may judge whether 3ABN's programming—consistent with Adventist teachings as to vegetarian cooking, healthful diets, smoking cessation, and Christian stewardship—falls outside of the state's concept of what is a "religious purpose" within the meaning of the statute. 3ABN responded that the state and its "courts should not undertake to dissect religious beliefs."16 In fact, a New York case, Holy Spirit Assn. for Unification of World Christianity v. Tax Commission of New York,17 agreed that civil courts are not competent to decide which activities that a religious organization engages in are religious.

Holy Spirit stated that the task in tax exemption cases is restricted to two inquiries: (1) Does the religious organization assert that the challenged purposes and activities are religious; and (2) Is that assertion bona fide or, in other words, sincere?18 Holy Spirit stated: "Neither the courts nor the administrative agencies of the state or its subdivisions may go behind the declared content of religious beliefs any more than they may examine into their validity."19

One Illinois court has subsequently adopted the Holy Spirit decision completely.20 But the Department of Revenue and school districts in the 3ABN case nonetheless want to inquire into the 3ABN programming content to ascertain if its activities primarily involve what the state deems to be traditional religious activities (i.e., baptisms, weddings, worship services, etc.). But Justice John Harlan in Walz said the administration of an exemption statute must "not entail judicial inquiry into dogma and belief."21

All of 3ABN's programming is religious in content and is permeated with Adventist teachings. Also, 3ABN distributes videos of its programs and CDs of religious music, as well as religious books and literature. The items are either given away free to viewers or sold at or below cost. Any money received from sales is used to maintain the ministry's operations. Most of its revenue is provided by donations from many thousands of 3ABN supporters. In fact, 3ABN could never operate without the support of its contributors.

But the school districts nevertheless argue that because 3ABN is "primarily a radio and television and television/satellite broadcasting, sales, and publishing corporation," its activities are secular rather than religious.22 And the Department of Revenue has bought into this argument as well.

In spite of the fact that the programming produced and aired—as well as the books, videos, CDs, and other materials distributed—is all completely religious in content, the school districts argue that 3ABN's purpose and use is not religious. They claim "that no portions of the subject properties are dedicated to traditional worship services open to the public."23

The Department of Revenue and school districts also argue that some of the videos, CDs, and books are sold rather than given free of charge, and that therefore it is a commercial enterprise. The state and school districts' position is similar to that of the government in Murdock v. Pennsylvania,24 a case dealing with a solicitation law providing for a licensing tax. The law had been applied to itinerant religious booksellers. The Murdock Court flatly declared: "But the mere fact that the religious literature is 'sold' by itinerant preachers rather than 'donated' does not transform evangelism into a commercial enterprise."25

In 3ABN's case, there are no stockholders, and no claim has been made or could be made that 3ABN officers or staff receive anything but very modest salaries. Its board of directors also serve without pay and provide their own travel expenses. Most of the board, in fact, have been continuing financial contributors to the 3ABN ministry.

The Supreme Court in Murdock rejected the idea, similar to that advanced by the Department of Revenue and school districts in the 3ABN case, that First Amendment protection of religious activities includes only church services, religious services, and prayers. Murdock concluded that the spreading of religious beliefs was equally protected, stating:

"The constitutional rights of those spreading their religious beliefs through the spoken and printed word are not to be gauged by standards governing retailers or wholesalers of books. The right to use the press for expressing one's views is not to be measured by the protection afforded commercial handbills. It should be remembered that the pamphlets of Thomas Paine were not distributed free of charge. It is plain that a religious organization needs funds to remain a going concern. But an itinerant evangelist, however misguided or intolerant he may be, does not become a mere book agent by selling the Bible or religious tracts to help defray his expenses or to sustain him. Freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of religion are available to all, not merely to those who can pay their own way."26

Certainly this argues that 3ABN, when distributing satellite dishes to view its religious programs and providing videos, CDs, and books, does not forfeit its equal treatment right underscored by the reality that state-imposed tax burdens are not being placed on other religious ministries. Murdock observed: "This form of religious activity occupies the same high estate under the First Amendment as do worship in the churches and preaching from the pulpits. It has the same claim to protection as the more orthodox and conventional exercises of religion. It also has the same claim as the others to the guarantees of freedom of speech and freedom of the press."27

That 3ABN is producing and distributing programming with the aim of carrying out its television ministry is the twenty-first century's variant of evangelism, which was the subject of Murdock.

It would violate religion clause principles to hold that religious organizations that require funds to carry on and expand their ministries should lose the tax exemption provided to other religious ministries not needing or seeking funds. Such an interpretation would violate neutrality principles.

The Supreme Court in a 1989 decision agreed with the New York Holy Spirit decision that there exists an "overriding interest in keeping the government—whether it be the legislature or the courts—out of the business of evaluating the relative merits of differing religious claims. The risk that governmental approval of some and disapproval of others will be perceived as favoring one religion over another is an important risk the establishment clause was designed to preclude."28

Attempts by the state to divide 3ABN's programming into "religious" and "secular" categories will inevitably result in a definition of religion oriented toward what the majority views as "religious." The Supreme Court recognized the pitfalls of this in Walz v. Tax Commission when, in upholding the constitutionality of tax exemptions for religious organizations, it noted that the government should not be partial to any one religious group and that the Court would "survey meticulously the circumstances of governmental categories to eliminate, as it were, religious gerrymanders."29

If, on a case-by-case basis, a claim to tax exemption because of a religious purpose and activity may be picked apart by those challenging the exemption, while popular religious groups' tax exemptions for their selected activities go unchallenged, the danger to religious neutrality becomes obvious. For the state to inquire into what activities are religious, contrary to the assertion of the religious organization, is fraught with constitutional dangers of governmental entanglement with religion. Justice Harlan's concurrence in Walz30 noted that "the more discriminating and complicated the basis of classification for an exemption—even a neutral one—the greater the potential for state involvement in evaluating the character of the organizations."

The 3ABN ministry asserts that all its activities on the property in question relate directly to the religious purposes and activities of 3ABN. The school districts challenged this assertion and undertook significant discovery on issues such as the number of employees at 3ABN who are "ministers" or who are employed in directly "spiritual" tasks, such as praying, preaching, or baptizing. The school districts also made searching inquiries into the square footage of the buildings that is used for preaching or pastoral purposes as compared to the square footage that relates to administration, accounting, mailing and printing services, engineering, computer graphics and media services.

These adversaries seem to argue that "worship activities" are the only truly religious activities occurring at 3ABN and that because "worship activities are only a part of what takes place on the property, the tax exemption must be denied." But such a narrow view, in addition to denying many activities that most people believe to be religious, would place Illinois tax exemption for churches and religious organizations in constitutional jeopardy. This is because churches themselves contain facilities and carry out operations that can be labeled as secular.

As Justice Brennan observed in Walz, that "appellant assumes, apparently, that church-owned property is used for exclusively religious purposes if it does not house a hospital, orphanage, weekday school or the like."31

Justice Brennan then perceptively added: "Any assumption that a church building itself is used for exclusively religious activities, however, rests on a simplistic view of ordinary church operations. . . . Even during formal worship services, churches frequently collect the funds used to finance their secular operations and make decisions regarding their nature."32

But the carrying out of these "secular operations" should not jeopardize the tax-exempt nature of the organization, as they are done in furtherance of the religious purpose. Similarly, the "secular" components of 3ABN's operations at the subject property should not call into question its property tax exemption. If this were to occur, all churches operating religious schools would have no basis for a religious property tax exemption for such activities, because much of their curriculum is not directly "religious," as in Bible or doctrinal classes, but includes topics such as math, science, spelling, and physical education.

But, as New York's highest court noted: "The fact that part of the curriculum includes secular subjects does not mean that the [school] facilities are being partly devoted to non-religious purposes. . . . Here the teaching of secular subjects by a religious school is an integral part of the church's belief that knowledge of the world should be conveyed and considered in a religious context."33

In that case the court focused on the fact that there "the teaching of religious beliefs is the paramount objective and that it pervades all subjects whether secular or religious."34

The Department of Revenue and school districts argued that a state-of-the-art television production studio and media distribution center, regardless of its religious content, is not entitled to real property tax exemption. It is disturbing that in this case evidence was excluded that the Department of Revenue had previously granted tax exemption to an almost identical Christian television network in an adjacent county. It was argued that such evidence was irrelevant to the issue of whether 3ABN's use of its property qualified it for the religious property tax exemption. The Department of Revenue claimed that "the Department and the State are not bound by their prior decisions with regard to other applicants."35

But 3ABN responded that in denying tax exemption to it while granting exemption to another television ministry, the Illinois Department of Revenue is guilty of "selective taxation." The network argued that a governmental entity may not pick and choose which religious messages of television ministries are entitled to tax-exempt status and which are not.

The Department of Revenue surprisingly argued that "there is little indication that the courts have meant to declare that government neutrality means equality of treatment." According to the Department of Revenue, "generally, the courts have usually discussed neutrality as the government's behavior vis-a-vis religion rather than government treatment of one religious entity vis-a-vis another."36

But the Supreme Court in Walz concluded that tax exemption for religious organizations did not violate the establishment clause only when one religious organization was not favored over another. It is constitutionally impermissible for the Department of Revenue to troll through 3ABN's religious programming and to refuse to acknowledge the constitutional requirement of the neutral administration of a statute in a way that does not result in selective determination of tax exemptions for the same religious activities.

In Corporation of Presiding Bishop v. Amos,37 the United States Supreme Court flatly stated that "laws discriminating among religions are subject to strict scrutiny." The Court clearly applied this principle to tax-exempt cases, stating that "government may neither compel affirmation of a repugnant belief, nor penalize or discriminate against individuals or groups because they hold religious views abhorrent to the authorities, nor employ the taxing power to inhibit the dissemination of particular religious views."38

In another Supreme Court decision, Hernandez v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue,39 Justice Sandra Day O'Connor in her dissent warned against the government's drawing a line between "taxable and immune" when "drawn with an unsteady hand."40 This, she concluded, would occur when there is "the differential application of a standard based on constitutionally impermissible differences drawn by government among religions."41 If, 3ABN argues, the Illinois Department of Revenue ultimately denies its tax exemption appeal after sifting through its programming without any fixed standard of distinguishing sacred from secular programming while the Christian television network in the next county enjoys tax exemption, the line between tax-exempt and taxable clearly will have been drawn with an unsteady hand.

A critical issue in the 3ABN case is how the Illinois Department of Revenue treats similarly situated religious media ministries. The Supreme Court has with great clarity spoken against the failure of the state to be religiously neutral. The Court stated that "facial neutrality is not determinative. The free exercise clause, like the establishment clause, extends beyond facial discrimination. The clause forbids subtle departures from neutrality."42

But, of course, the reason behind the attack on 3ABN's claimed religious activities presents a much larger concern. The arguments presented against this worldwide television and radio network ministry are simply derived from the government's hunger for more money. If 3ABN loses its fight, other religious ministries involving more than television and radio will surely be challenged not only in Illinois but everywhere in this country. Society will be much poorer if the state wins these battles. There is no better expression of the concerns posed in this fight than that expressed by the Supreme Court in Walz when it stated:

"Governments have not always been tolerant of religious activity, and hostility toward religion has taken many shapes and forms—economic, political, and sometimes harshly oppressive. Grants of exemption historically reflect the concern of authors of constitutions and statutes as to the latent dangers inherent in the imposition of property taxes; exemption constitutes a reasonable and balanced attempt to guard against those dangers."43

____________

Lee Boothby writes from Washington, D.C., and is an experienced litigation and appellate court lawyer, who has argued a number of First Amendment cases before the Supreme Court. President of the Commission on Freedom of Conscience, he specializes in religious liberty issues worldwide.

____________

1 Walz v. Tax Commission of New York City, 397 U.S. 664, 676,677 (1970).

2 35 ILCS