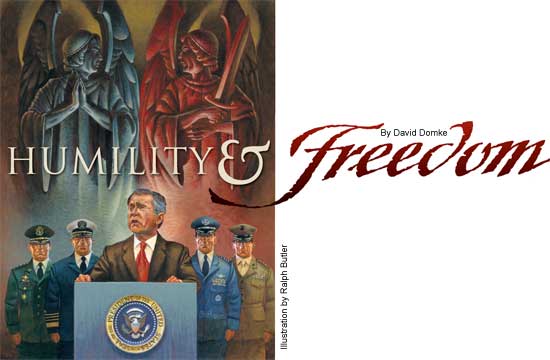

Humility and Freedom

David Domke September/October 2005

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Since the evening of September 11, 2001, when George W. Bush quoted Psalm 23 and declared the day's events to be the opening salvo of a cosmic struggle of good versus evil, there has been a heated public debate about his openly religious language. Standard and appropriate, or unusual and dangerous? The latter, say more than 200 U.S. seminary and evangelical leaders who last October signed a petition condemning what they called a "theology of war" regarding the administration's convergence of God and nation in the campaign against terrorism. One of the signers is Sojourners magazine editor-in-chief, Jim Wallis, whose book God's Politics: Why the Right Gets It Wrong and the Left Doesn't Get It became a national best seller in early 2005. In chapter one Wallis says this: "I have never seen such outrageous behavior by a political party in trying to manipulate religion for its own agenda while so disrespecting the faith of millions of other believers who disagree with the Republican political agenda." Not so, say many administration officials and supporters who consistently have claimed that President Bush's mixture of religion and politics is nothing new in the American presidency. Reverend Richard John Neuhaus, editor of the journal First Things, told the Washington Post last September that "there is nothing that Bush has said about divine purpose. . . that Abraham Lincoln did not say. This is as American as apple pie." Similarly, Michael Gerson, Bush's primary speechwriter during his first term, told a group of journalists in December that "it's not a strategy," "it's also not new," and "I don't believe that any of this is a departure from American history." Perhaps both have a point.

The Gospel of Freedom and Liberty

Among these instances was this declaration in the inaugural: "We have confidence because freedom is the permanent hope of mankind, the hunger in dark places, the longing of the soul. When our Founders declared a new order of the ages; when soldiers died in wave upon wave for a union based on liberty; when citizens marched in peaceful outrage under the banner 'Freedom Now'—they were acting on an ancient hope that is meant to be fulfilled. History has an ebb and flow of justice, but history also has a visible direction, set by liberty and the Author of Liberty."

Freedom. Liberty. God. These emphases by Bush are as mainstream as one will find in U.S. presidential rhetoric. Only one inaugural address, George Washington's second, makes no mention of a divine presence. Similarly, freedom and liberty are principles deeply ensconced in the American experience and identity, enshrined in more than 500 literal symbols of liberty and freedom, according to Brandeis University historian David Hackett Fischer. In emphasizing a higher power along with freedom and liberty, Bush is, as his supporters contend, doing nothing new.

However, that is not the whole story. For while Bush's points of emphasis are not uncommon for the presidency, the way in which he connects God with freedom and liberty is distinctive. And dangerous, some might reasonably argue. Let's think about this for a moment.

The president offers a distinctly evangelical worldview regarding the appropriate role of the United States in the post-September 11 world. Central to this outlook is the "Great Commission" biblical mandate, in the book of Matthew, to "go therefore and make disciples of all the nations" (28:19, NKJV).* In the eyes of Bush's core political constituency, Christian conservatives, the desire to live out this biblical command has become intertwined with support for the principles of political freedom and liberty. In particular, the individualized religious liberty present in the United States (particularly available historically for European-American Protestants) is something that religious conservatives long to extend to other cultures and nations.

In the 1980s fundamentalist preacher and leader Jerry Falwell argued that the dissemination of Christianity could not be carried out if other nations were Communist—a perspective that provided a good reason to support Ronald Reagan's combination of a strong U.S. military, conservative foreign policy, and the spreading of individual freedoms. In that era Falwell told his flock that they could "vote for the Reagan of their choice." Falwell echoed this perspective in 2004, saying in the July 1 issue of his e-mail newsletter and on his Web site, "For conservative people of faith, voting for principle this year means voting for the reelection of George W. Bush. The alternative, in my mind, is simply unthinkable."

The certitude in the support for Bush by Falwell (and by other Religious Right leaders such as James Dobson, Pat Robertson, and Gary Bauer) is emblematic of fundamentalists' confidence that their understanding of the world provides what religion scholar Bruce Lawrence terms "mandated universalist norms" to be spread across cultural and historical contexts. For Bush and the Religious Right, those norms first and foremost are U.S. conceptions of freedom and liberty. Since September 11 these values have gained a special resonance among Americans—and the administration—because of genuine ideological, as well as strategic, reasons. Since the attacks Bush has often done what other presidents have rarely done: claimed that the freedom and liberty he seeks to spread is God's will for the world.

In his address before Congress and a national television audience nine days after the terrorist attacks, Bush declared, "The course of this conflict is not known, yet its outcome is certain. Freedom and fear, justice and cruelty, have always been at war, and we know that God is not neutral between them."

In the 2003 State of the Union address, with the conflict in Iraq imminent, Bush declared, "Americans are a free people who know that freedom is the right of every person and the future of every nation. The liberty we prize is not America's gift to the world; it is God's gift to humanity."

In his address at the Republican Party Convention in September 2004, Bush made this claim: "I believe that America is called to lead the cause of freedom in a new century. I believe that millions in the Middle East plead in silence for their liberty. I believe that given the chance, they will embrace the most honorable form of government ever devised by man. I believe all these things because freedom is not America's gift to the world; it is the Almighty God's gift to every man and woman in this world."

And as he began his second term, Bush in his inaugural called God the "Author of Liberty," then two weeks later in his State of the Union address said: "We live in the country where the biggest dreams are born. The abolition of slavery was only a dream—until it was fulfilled. The liberation of Europe from fascism was only a dream—until it was achieved. The fall of imperial communism was only a dream—until, one day, it was accomplished. Our generation has dreams of its own, and we also go forward with confidence. The road of Providence is uneven and unpredictable—yet we know where it leads: It leads to freedom."

Some might wonder if many of these words should be attributed to Gerson, a graduate of evangelical Wheaton College who was hired in 1999 by Bush and subsequently became the primary speechwriter for the White House. The words are Bush's.

Bob Woodward, in his book about the administration's push toward Iraq, Plan of Attack, includes this quote from Bush: "I say that freedom is not America's gift to the world. Freedom is God's gift to everybody in the world. I believe that. As a matter of fact, I was the person that wrote the line, or said it. I didn't write it, I just said it in a speech. And it became part of the jargon. And I believe that. And I believe we have a duty to free people. I would hope we wouldn't have to do it militarily, but we have a duty."

A New Manifest Destiny?

The claim that the U.S. government is doing God's work may appeal to many Americans, but it frightens those who might run afoul of administration wishes-cum-demands. This is particularly so when one considers how declarations of God's will have been used by European-Americans in past eras as rationale for subjugating those who are racially and religiously different, most notably Native Americans, Africans, Chinese, and African-Americans.

Indeed, religion scholar R. Scott Appleby in 2003 declared that the administration's omnipresent emphasis on freedom and liberty functions as the centerpiece for "a theological version of Manifest Destiny." If so, one must note the risk of repeating today what previous versions of Manifest Destiny did in the past: unduly emphasizing the norms and values of White religiously conservative Protestants at the expense of those who will not or cannot conform. At a minimum the president's rhetoric has, by implication, transformed Bush's "Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists" policy to "Either you are with us, or you are against God."

Such a view sounds eerily similar to that of the terrorists we are fighting. Indeed, one might be hard pressed to discern how Bush's declarations that the United States is delivering God's wishes to the Taliban or in Iraq differ from the rhetoric of Osama bin Laden, that he and his followers are delivering God's wishes for the United States.

The answer, then, to whether George W. Bush's religious language differs from that of previous presidents lies in the details of the discourse. It's not in his choice of words; it's in how he puts the words together—which, of course, is always one short step from how he puts his policies together. One might hope that this president, who spoke after his reelection of spending his newly earned "political capital," might recall the words of Saint Augustine of Hippo to a student: "I wouldn't have you prepare for yourself any way of grasping and holding the truth other than the one prepared by Him who, as God, saw how faltering were our steps. That way is, first, humility; second, humility; third, humility; and as often as you ask, I'll tell you, humility."

___________________________

David Domke is an associate professor in the Department of Communication at the University of

Washington. He is the author of God Willing? Political Fundamentalism in the White House,

the "War on Terror," and the Echoing Press (Pluto Press, 2004).

___________________________

*Texts credited to NKJV are from the New King James Version. Copyright