In the Shadow of the Capitol

Trevor Delafield January/February 2006

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Liberty magazine, which is just completing 100 years of continuous publication under its own name, had several precursor Seventh-day Adventist religious liberty magazines, starting with the American Sentinel magazine (1886-1900). With the exception of a few months in 1900 and 1901, when it was published by the International Religious Liberty Association in Chicago as The Sentinel of Liberty, the magazine was published by Pacific Press, either at Oakland, California, or its branch office in New York. However, in 1903 the immediate precursor of the magazine, Sentinel of Christian Liberty (1901-1904), was moved from New York to Washington, D.C., where the New York branch of the Pacific Press was combined with the newly reorganized Review and Herald Publishing Association. A disastrous fire in Battle Creek, Michigan, had led to the removal of the Review and Herald and the Seventh-day Adventists Church headquarters from Battle Creek to Washington.

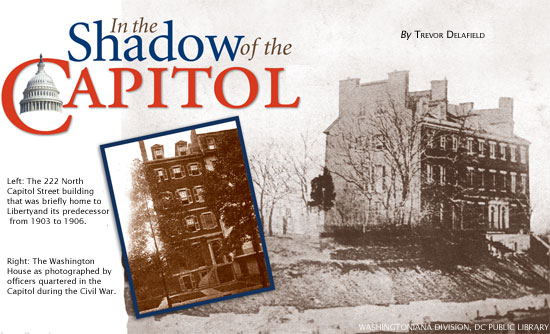

The new home of the magazine, 222 North Capitol Street, N.W., itself had risen from the ashes of a famous fire—it had been burned during the British invasion of Washington in 1814. The building that was occupied from 1903 to 1906 as the temporary headquarters of the Review and Herald, and the first and last Washington home of the precursor magazine to Liberty, was added as a third residence of an original two-part town house built in 1799.

Portions of the building that later became 222 North Capitol may have been added at the time of the original 1818 reconstruction, or perhaps later, in the 1830s. This structure, which incorporated walls from the original house, bore a strong resemblance to the 1799 house. From henceforth the two new structures were inseparably connected and came to be known together as the Washington House. A Civil War-era photograph, which some reports indicate was taken by Matthew Brady, shows marble slabs lying on the roadway, ready for transportation to the nearby Capitol building, which was undergoing remodeling. According to an early source, Abraham Lincoln interviewed the defender of Fort Sumter in this house after the fort's fall.

George Washington had a personal hand in the design of the house and wanted it to include features of a house in Philadelphia that appealed to him, perhaps the house of Colonel Isaac Franks, a revolutionary officer who made his residence available to the president upon Washington's request. Washington had stayed in the Franks house, which was located in what was then the outskirts of the city, during a yellow fever epidemic in 1793.

Washington wanted the house to be completed before the first session of Congress in the new Federal City commenced in 1800, as mandated by law. He visited the site while the house was under construction, but it was uncompleted when he died unexpectedly in December 1799. The president planned his house as a modest residence in terms of formal houses of the time. However, he considered that when completed, it would be the finest residence then standing on Capitol Hill. It was his intention that the house could be used as a single dwelling or as separate houses. He said that it could, if necessary, house from 20 to 30 persons.

After Washington's death the house remained in the trust of the George Washington estate and served as a congressional boardinghouse from the first meeting of Congress in 1800 until August 23, 1814. That was when it was destroyed by fire, perhaps intentionally by the British, who may have learned that papers from the House of Representatives, mainly "committee records, claims and pensions, and revolutionary claims," had been moved there for safekeeping, apparently by John Frost, a clerk in the House of Representatives and son of Mrs. Frost, who "conducted" the boardinghouse. The properties were rented for boardinghouse purposes by the Frosts from 1800 on. "A part of it was occupied by President Jefferson's Secretary of War, Gen. Henry Dearborn."

After the fire the ruins were sold by Washington's estate to David English and W. S. Nichols. English sold his interest to Peter Morte, who incorporated the walls of the old building into the rebuilding of the home.

From the beginning the newly reconstructed house was also envisioned as being suitable for use as a large single residence, or as two separate structures. Subsequently it was apparently utilized in both ways. Prior to the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, the house, or a portion of it, served as the home of Admiral Charles Wilkes, an Antarctic explorer.

For a number of years the original two-part house, which had once again become a single unit, as remodeled, served as a hotel and boardinghouse. As originally laid out, the house had "three full stories and a dormer story." At some time subsequent to 1861, "changes in the street grade compelled the addition of a lower story and an English basement." Admiral Wilkes had wanted to make some accommodation in the building to the changes in the street grade in the 1850s, but this did not take place until some time later, perhaps when it was laid out for use as a hotel. It was this configuration of the building that was in place at the time of the 1903-1906 Seventh-day Adventist occupancy of the location.

The last numbers of the Sentinel of Christian Liberty were issued in 1904 at the 222 North Capitol address. After a brief hiatus, however, in 1906, a new, refurbished magazine appeared under the new name Liberty, which has been its name ever since. The first numbers of the new magazine used the address Takoma Park Station, Washington, D.C. The first issue (dated April 1906) was actually printed the week of March 15, and as operations had not yet begun in the new building, it is probable that the first number, and a previous undated special number of the new publication were actually printed at 222 North Capitol Street, N.W. While the publishers wanted the new magazine to be identified with the new location next to the new denominational headquarters in Takoma Park, the first and last home of the precursor magazine became the first home of Liberty magazine.

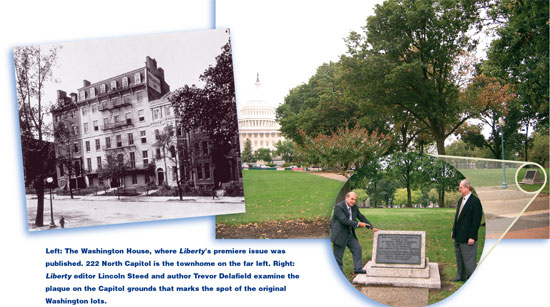

Ten years after the Seventh-day Adventists first occupied it, the building was demolished to make room for the expansion of the Capitol grounds. While demolition was probably completed by 1914 or 1915, the improvements to the Capitol grounds were delayed by the onset of World War I. For a number of years Square 634, the location of the Washington town house lots, was the site of a temporary structure, Administrative Building No. 2, built in 1918 to house government workers. This building remained on the grounds until 1930 when work resumed on the expansion of the Capitol Grounds.

Materials salvaged from the Washington houses, some presumably from George Washington's own possessions, were incorporated into a new hotel, the George Washington Inn. Phillips was president and manager. When it was demolished, however, in 1964, this building housed the staff of congressional committees, who were moved into the new Rayburn House Office Building. The location is now a park on part of the Capitol grounds, located opposite the Longwood House Office Building, at the southeast corner of C Street and New Jersey Avenue, S.E.

By 1930 the North Capitol site was once again cleared, and work on a new park, which would extend between the Capitol and Union Station, began in earnest. The development of the areas, including fountain, reflecting pool, and plantings, was completed in November 1932. A historical plaque marking the spot of the original Washington lots and the reconstructed and enlarged house was installed under the direction of David Lynn, architect of the Capitol, in 1932, the bicentennial of the birth of Washington.

When the Adventist Church moved its headquarters to the 222 North Capitol address in 1903, the reconstructed building probably better reflected Washington's intention for his Washington homes than the original house. At the time of their occupancy and at the time of the razing of the entire structure, the third house, 222 North Capitol, retained the dormer walls and windows, but not the parapet or pediment Washington wanted. By this time many of the original architectural features of the original house, then called 224 North Capitol, were gone; a mansard roof (probably installed at the time the additional floors were added to the building) replaced the original dormer windows. However, the entire building was called the Washington House.

As is true with many buildings that serve different uses over the span of their lifetime, the building on North Capitol Street served in some noteworthy ways, and in some ways that were not quite so illustrious. It even achieved some notoriety. For their part, the Adventists were aware of the history and significance of the building and its location. They knew it as the Washington House, referred to it as such, and were pleased to occupy a building having such a connection with the history of the nation.

Interviewed in the January 20, 1952, issue of The Evening Star, on the occasion of his eighty-sixth birthday, W. A. Spicer, then the sole surviving member of the committee that was assigned the task of finding a new location for the Seventh-day Adventist Church headquarters in 1903 and a former president of the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists, recalled the fact that their first home in Washington was built for President Washington, and said, "We were proud that our prayers had guided us to such a historic beginning in the Nation's Capital."

On the occasion of the printing of the first number of the Sentinel of Christian Liberty in Washington, the Review and Herald, the general church paper, commented: "The first issue of The Sentinel of Christian Liberty from its new home in this city appeared last week. The issue which called this paper into existence is still a living one, and the principles which it advocates ought to be taught to all the people. It is now published under the very shadow of the Capitol building, where the laws of the nation are made, and it ought to carry the message of Christian liberty through all the land. We hope that its present circle of readers may be greatly enlarged in the near future."

___________________________

Trevor Delafield, D. Min., is a Seventh-day Adventist minister with a keen interest in American church history. He first acquired his appreciation for American religious and civil liberties while reading copies of Liberty magazine around the house when he was a boy in a minister's home, and he is a lifelong admirer of the magazine.

1 Anthony S. Pitch, The Burning of Washington: The British Invasion of 1814 (Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 1998), p. 113.

2 John Clagett Proctor, "Houses Once Owned by Washington," The Sunday Star, Washington, D.C., Sept. 27, 1931.

3 James Croggon, "New Plaza Takes Washington Inn" (unnamed periodical, Sept. 20, 1913), "George Washington's House in Washington," Frank W. Hutchins, The Sunday Star, Washington, D.C., Feb. 16, 1930.

4 Proctor.

5 Review and Herald, Apr. 26, 1906; May 31, 1906.

6 Hutchins.

7 Washington Post, May 2, 1964.

8 The Sunday Star, Feb. 16, 1930.

9 Review and Herald, Oct. 22, 1903.

___________________________