Incident at East Waynesville

Chase Adams September/October 2005

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Whatever happened to religious freedom in America? After all, isn't it preaxiomatic that a church has the right to determine for itself what is required for membership? If the free exercise clause means anything, it means that a church should be able to require any kind of belief, no matter how ludicrous. If it wants the faithful to believe that we're descendants of aliens, it should have right to kick out those who stray from that orthodoxy. If it requires you to believe that its leader is finishing the job that (according to its own theology) Jesus failed to do because His work was interrupted by the cross, then the church has the right to disfellowship those who reject that view. If members are required to believe that Jesus once came to the Americas and witnessed to people there, then it has the right to discipline, or even boot out, those who deny that belief. If that's not religious freedom, what is?

If this concept is so fundamental, then why all the screeching earlier in the year when a Baptist minister in North Carolina was accused of kicking out members who didn't vote Republican in the most recent presidential election? Are we now telling churches what they can and cannot require for church membership? Does not a church have the right to require members vote in a certain way in order to be part of that fellowship? Is not it a violation of the most fundamental principles of church-state separation when a church is not allowed to demand certain beliefs, or actions, of church members, just as long as those actions do not violate the law?

In other words, churches can require members to believe anything, and it's not the government's business to dictate those beliefs or to determine internal church discipline when someone is deemed to have strayed from "truth." Indeed, unless property rights are involved, or there is a violation of the law, the government generally stays away. True religious freedom demands, it would seem, nothing less.

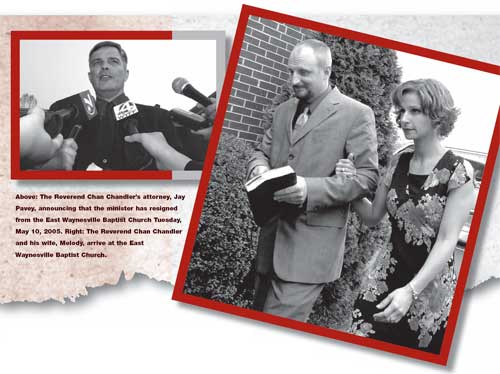

Thus, when the Reverend Chan Chandler, of the East Waynesville Baptist Church, in Waynesville, North Carolina, supposedly told church members that anyone who planned to vote for John Kerry should either leave the church or repent, he was truly exercising religious freedom. Putting aside, for the moment, the slight question of the church's 501(c)(3) status (tax exemption), the pastor was within his rights. If the church wanted to throw out anyone who didn't vote for Bush, or swear undying fealty to the GOP ("God's Own Party"), or burn incense on the altar to the war god, that's its right, guaranteed by the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution itself, and it would be a sad day in America were the government, at any level, to step in and force it otherwise.

There's a great lesson to be learned from this story, and it gets to the genius of the American experiment with religious liberty.

Of course churches have the right to promote and teach anything they want; but people have the right to protest, to leave, to contact the press, and to make a royal hoopla about it too. In many ways it's the market that drives the engine of faith in this country, and it's the way it should be. People are free to promote and teach and propagate all the nonsense they want; they just need to be prepared to face the consequences, that's all, especially in what's been deemed the "marketplace of ideas." This is a free country. You can believe whatever you want to and promote just about whatever you want to as well. At the same time, however, people are just as free to oppose your actions and your beliefs, and if you are humiliated, mocked, or driven into obscurity because of your actions, well. . . that's what freedom is all about.

And we got a great example of that principle with the East Waynesville Baptist Church. The screeching fantods caused by Chandler's actions did all that was necessary to remedy the situation: Chandler's out, and some of the apostates seem to be heading back. All without any government coercion, regardless of whatever potential lawsuits might arise. This is the essence, and the beauty, of religious freedom. Preach, teach, promote whatever you want; make membership requirements as strict as you want; demand from your members whatever you want. Just be prepared to accept the consequences, that's all.

Thus, while ballyhooed as an example of a church crossing the line on religious liberty, the incident at East Waynesville Baptist Church is really a great example of religious freedom being manifested at its finest. Though Americans United for Separation of Church and State wrote to the IRS about the church having possibly violated Section 501(c)(3) of the tax code, which prohibits church and public charities from endorsing candidates for public office, it's probably a moot point now that Chandler is out. No doubt too, the ensuing publicity will make whoever follows a lot more circumspect as well.

In short, the incident at East Waynesville is proof that the principles of church-state separation work. Though the line between God and Caesar isn't always easy to define, when it's crossed big-time, as is apparently what happened from Chandler's pulpit, market forces have proved themselves more than capable of remedying the situation.

___________________________

Chase Adams is a journalist with a penchant for the unusual angle. He writes from Washington, D.C. ___________________________