Justice & Religion

David A. Pendleton September/October 2010

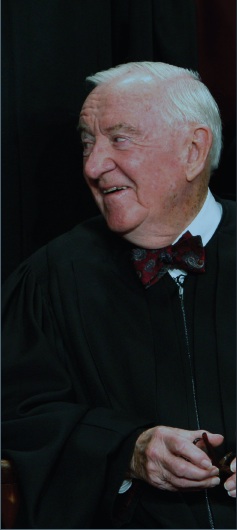

On April 9, 2010, Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens tendered his resignation letter to the president.1 Within hours, considerable commentary and conjecture deluged the Internet. Legal pundits and law professors agreed that the 90-year-old justice was in some respects irreplaceable. His closely reasoned opinions have helped fashion the very warp and woof of our constitutional fabric since his appointment in 1975 by President Gerald Ford.

Then on May 10, 2010, President Obama nominated Solicitor General Elena Kagan to fill the impending vacancy. While there are certainly

serious ideological opponents to her, it immediately became apparent that she would be confirmed to the position. The "$64,000 Question" on everyone's mind was how she might alter the direction of the Court. Conventional wisdom suggests that replacing a liberal-leaning justice with a liberal-leaning successor shouldn't change things.2 But before entertaining further prognostications, a baseline needs to be drawn. Logically antecedent to a prediction of where the Court is going is consideration of where it has been.

Of particular interest to many Americans in this post-9/11 era is the issue of religion. As provided in the Bill of Rights, "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof." In these first clauses of the First Amendment is fixed firmly the freedom to exercise one's religion and to be free from government establishment of religion.

Bismarck's legendary quip about it being best that we not witness the production of laws or sausages may be witty and truthful as to the bloody work of butchers, but ignorance is not bliss when it comes to the work of any branch of government. A flourishing democracy requires an informed and active citizenry holding government accountable for its decisions.

And Justice Stevens' numerous opinions and dissents elucidating the free exercise clause and the establishment clause have been commended and criticized. Some adore, and others abhor, his jurisprudence—but few are indifferent to what he has to say. Consider Salazar v. Buono.3 Decided on April 28, 2010, this case concerned the hilltop cross on federal land in the Mojave Desert planted there by veterans as a memorial. Plaintiff Buono sued, arguing that a religious symbol on government property was an impermissible governmental establishment of religion. A federal district court agreed, granting an injunction. Then Congress prevented the removal of the cross, voting to transfer the government land beneath it to the Veterans of Foreign Wars, presumably to cure the establishment problem.

Consider Salazar v. Buono.3 Decided on April 28, 2010, this case concerned the hilltop cross on federal land in the Mojave Desert planted there by veterans as a memorial. Plaintiff Buono sued, arguing that a religious symbol on government property was an impermissible governmental establishment of religion. A federal district court agreed, granting an injunction. Then Congress prevented the removal of the cross, voting to transfer the government land beneath it to the Veterans of Foreign Wars, presumably to cure the establishment problem.

The district court blocked Congress' land transfer with an injunction, which the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed. Upon reaching the Supreme Court, the splintered Court issued a plurality opinion by Justice Kennedy reversing and remanding, effectively delaying removal of the cross.

In dissent, Justice Stevens, joined by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Justice Sonia Sotomayor, observed that a "Latin cross necessarily symbolizes one of the most important tenets upon which believers in a benevolent Creator, as well as nonbelievers, are known to differ. . . . Congress' proposed remedy . . . was engineered to leave the cross intact and . . . did not alter its basic meaning. . . . [T]he Nation should memorialize the service of those who fought and died in World War I, but it cannot lawfully do so by continued endorsement of a starkly sectarian message."

Because a memorial's raison d'être is to convey a message, Justice Stevens opined that there would "be a clear establishment clause violation if Congress had simply directed that a solitary Latin cross be erected on the Mall in the Nation's Capital to serve as a World War I Memorial." And while the government "did not erect this cross," congressional intervention "gave the cross the imprimatur of Government." Far from healing the constitutional infirmity, the land-swap scheme was a nostrum serving to, in the estimation of Justice Stevens, "perpetuate rather than cure that unambiguous endorsement of a sectarian message."

Although in early May of 2010 the cross was stolen, questions of government endorsement of religion are not so easily carried off. Van Orden v. Perry4 involved a massive six-foot-tall granite Ten Commandments monument reportedly donated with the support of Cecil B. DeMille, director of the film The Ten Commandments. Situated among other monuments, it graced the Texas state capitol grounds. In a 5-4 vote, the Supreme Court held it a permissible secular message, because it was "passive" and gave but historic acknowledgment of the role played by the Ten Commandments in Texas' extraordinarily colorful history.

Justice Stevens, joined by Justice Ginsburg, dissented, explaining that private parties "may donate as many monuments as they choose to be displayed in front of Protestant churches, benevolent organizations' meeting places, or on the front lawns of private citizens. The expurgated text of the King James version of the Ten Commandments that they have crafted is unlikely to be accepted by Catholic parishes, Jewish synagogues, or even some Protestant denominations, but the message they seek to convey is surely more compatible with church property than with property that is located on the government side of the metaphorical wall."

This dissent echoed similar concerns from an earlier case, Zelman v. Simmons-Harris,5 which in 2002 examined Ohio's Pilot Project Scholarship Program. The program provided, among other things, tuition aid to certain students in Cleveland to enroll in select religious and nonreligious schools. Ohio taxpayers filed suit, but the Supreme Court found the program passed constitutional muster.6

In dissent Justice Stevens asked the obvious question: "Is a law that authorizes the use of public funds to pay for the indoctrination of thousands of grammar school children in particular religious faiths a 'law respecting an establishment of religion' within the meaning of the First Amendment?" Alluding to President Thomas Jefferson's celebrated metaphor, Stevens warned that when "we remove a brick from the wall that was designed to separate religion and government, we increase the risk of religious strife and weaken the foundation of our democracy." (One wonders whether the Court would have upheld tuition aid for madrassa students to be indoctrinated in radical Islam and violent jihad.)

Justice Stevens was not always on the losing side. His majority opinion in Santa Fe Independent School Dist. v. Doe7 interrogated whether it was a legitimate government function to facilitate and orchestrate prayer. Prior to 1995, a prayer was said over the public-address system before football games at a public school in Santa Fe.

Presumably because of the content or tone of some prayers, Mormon and Catholic students filed suit challenging the constitutionality of such prayers, whereupon the school district changed its policy, which thereafter provided for election of the student to deliver the prayer and specified guidelines to ensure the prayers were nonsectarian and nonproselytizing.

Justice Stevens, writing for the Court, held the policy as "invalid on its face because it establishes an improper majoritarian election on religion, and unquestionably has the purpose and creates the perception of encouraging the delivery of prayer at a series of important school events."

The subtext is that prayer is too important to entrust to the government. By definition, prayer freely addresses the Almighty. When government determines who can pray and dictates what is prayed, it has become excessively entangled in the practice of religion. Indeed, in Wallace v. Jaffree,8 Justice Stevens opined that "individual freedom of conscience protected by the First Amendment embraces the right to select any religious faith or none at all. . . . [R]eligious beliefs worthy of respect are the product of free and voluntary choice by the faithful.".jpg) Westside Community Bd. of Ed. v. Mergens9 provided Justice Stevens an opportunity to elucidate the theme of extricating government from religious practice. This plurality decision dealt with Westside Public High School, which recognized clubs but denied the request of students to form an officially recognized Christian club. The board upheld the denial, whereupon a lawsuit was filed under the federal Equal Access Act. The Supreme Court concluded that the school violated the act.

Westside Community Bd. of Ed. v. Mergens9 provided Justice Stevens an opportunity to elucidate the theme of extricating government from religious practice. This plurality decision dealt with Westside Public High School, which recognized clubs but denied the request of students to form an officially recognized Christian club. The board upheld the denial, whereupon a lawsuit was filed under the federal Equal Access Act. The Supreme Court concluded that the school violated the act.

Writing in dissent, Justice Stevens underscored the importance of asking the right question: "Can Congress really have intended to issue an order to every public high school in the Nation stating, in substance, that if you sponsor a chess club, a scuba diving club, or a French club—without having formal classes in those subjects—you must also open your doors to every religious, political, or social organization, no matter how controversial or distasteful its views may be?"

His vigorous dissent made clear that he did not think so. Indeed, he warned that the majority's interpretation of the act "leads to a sweeping intrusion by the Federal Government into the operation of our public schools . . . [and threatens to] divest local school districts of their power to shape the educational environment."10

That same year Justice Stevens joined the Court's majority opinion in the controversial and much maligned free exercise clause opinion authored by Justice Antonin Scalia, Employment Division, Department of Human Resources of Oregon v. Smith.11 The gravamen of the case was whether peyote-smoking drug rehab counselors were entitled to religious exemptions from a state criminal law banning peyote use. The Court held that such laws would no longer be evaluated under the balancing test and compelling state interest requirement of Sherbert v. Verner.12 The government could enact generally applicable criminal laws, religious exemptions to which might be constitutionally permitted but would not be required. Thus, peyote smoking was illegal—even for observant Native Americans for whom it was a sacrament.

Justice Stevens agreed with the majority that while an exception for sacramental peyote use might be constitutionally permissible, it was not constitutionally obligatory. When it came to free exercise, he had faith that whether a carve-out was appropriate was best left to the democratic process.

It is not necessary to parse all of the opinions of Justice Stevens to discern a meaningful pattern. One might summarize the approach of Justice Stevens in a précis: replace complicated balancing tests with bright lines; defer to political branches for exceptions to generally applicable laws.

More specifically, what emerges from his establishment clause writings is a robust wall of separation, which forbids state subsidizing of religious institutions and practices, disfavors most tuition voucher programs for religious schools, and prohibits religious displays on government property.

As to the free exercise clause, Justice Stevens believes religious institutions have the political clout and civic sophistication to advocate their own interests in city halls, state legislatures, and Congress. So government may (but is not constitutionally obliged to) provide exemptions to neutral and generally applicable laws incidentally burdening religious conduct.

Christopher L. Eisgruber, who clerked for Justice Stevens from 1989 to 1990 and is now provost at Princeton University, has written scholarly commentary that corroborates this.13 Similarly, Professor Eduardo M. Peñalver of Cornell Law School, who also clerked for Justice Stevens, concurs. Those who caricature Justice Stevens as one who "hates religion" are in error, for he possessed an abiding "respect [for] religion as a powerful motivator of human action, though one that is largely able to look out for its own interests in the political process."14

Some describe Justice Stevens as gleefully enforcing the establishment clause but only lukewarmly entertaining free exercise claims. Such appraisals fall somewhere on the spectrum between oblique obloquy and candid criticism. A sincere (but mistaken) perspective is Professor Douglas Laycock's charge that, for Justice Stevens, religion is "subject to all the burdens of government, but entitled to few of the benefits."15 Professor Michael Kessler disagrees: "Far from hostility to religion, Stevens's jurisprudence reflects this deep Jeffersonian conviction that religious freedom will suffer when a majority uses the rule of law to enforce its religious preferences."16 And Brent Walker of the Baptist Joint Committee has said that Justice "Stevens has been more champion than enemy of religious freedom."17

Practical and Accurate

In his prescient book John Paul Stevens and the Constitution, Professor Robert Judd Sickels explains that Justice Stevens saw "the Court's accretion of imprecise tests [as making] it difficult for legislators and judges to know what is lawful and what is not." This has not been good for either government or people of faith. In fact, Sickels understands that "Stevens's views of religious establishment reflect his concern that judge-made rules be practicable as well as historically accurate." And with a nod to Ockham's razor, "[o]ther things being equal, the simpler rule is the more workable."18 Arguably Justice Stevens preferred an incremental approach to constitutional adjudication—like a judicial Georges Seurat meticulously painting a pointillist masterpiece.

While Justice Stevens has been the recipient of admiration, condemnation, and misinterpretation—and will be for the foreseeable future—his constitutional oeuvre will inform judges, instruct citizens, and illuminate the Constitution for years to come. With his unwavering commitment to the wall of separation between church and state, complemented by his appreciation for the ability of institutionalized religion to participate meaningfully in the democratic process, Justice Stevens has left a religious liberty legacy for which we can be grateful.

1 www.talkingpointsmemo.com/documents/2010/04/justice-john-paul-stevens-resignation-letter.php?page=1.

2 "Notwithstanding the turnover, it is still a Justice Kennedy court," said Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of UC Irvine Law School, as a member of a panel discussion including the yet-to-be-nominated Elena Kagan. "Justice Kennedy has been in the majority of more 5-4 decisions than any other Justice over the last 4 years." — "Elena Kagan, Paul Clement, and Erwin Chemerinsky on SCOTUS 2009 Term," May 5, 2010, www.ocjblog.com/?p=4595.

3 559 U.S. ____ (2010). www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/08-472.ZC.html

4 545 U.S. 677 (2005). http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/scripts/getcase.pl?court=US&invol=03-1500&vol=000. Justice Stevens also warned that "[t]he judgment of the Court in this case stands for the proposition that the Constitution permits governmental displays of sacred religious texts. This makes a mockery of the constitutional ideal that government must remain neutral between religion and irreligion. If a State may endorse a particular deity's command to 'have no other gods before me,' it is difficult to conceive of any textual display that would run afoul of the establishment clause." Some observers wonder how this case can be reconciled with a similar case in which, voting 5-4, the Supreme Court found inappropriate a Ten Commandments display on government property. Some speculate that the Van Orden v. Perry case is sympathetic because the display had been there since 1961. Apparently, recently constructed religious displays on government property are verboten, but older displays will be grandfathered in.

5 536 U.S. 639 (2002).www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/historics/USSC_DN_0000_1751_ZO.html. Government-subsidized religious instruction, Justice Stevens cautioned, may lead to religious strife, the avoidance of which was one of the reasons for the establishment clause—an interpretation influenced and confirmed by "the impact of religious strife on the decisions of our forbears to migrate to this continent, and on the decisions of neighbors in the Balkans, Northern Ireland, and the Middle East to mistrust one another."

6 The suit alleged establishment clause violations, for which the federal district court granted plaintiffs summary judgment, and which the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed. Chief Justice William Rehnquist crafted the majority opinion upholding the Ohio tuition aid program.

7 530 U.S. 290 (2000).www4.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/99-62.ZO.html

8 472 U.S. 38 (1985). www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/historics/USSC_CR_0472

_0038_ZO.html

9 496 U.S. 226 (1990). http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/scripts/getcase.pl?navby=

0case&court=US&vol=496&page=226. Examining the school policy, the federal statute, and case precedent, Justice Stevens contended that the Court should "construe the Act [such that] a high school could properly sponsor a French club, a chess club, or a scuba diving club simply because their activities are fully consistent with the school's curricular mission . . . . Nothing in [the law] implies that the existence of a French club, for example, would create a constitutional obligation to allow student members of the Ku Klux Klan or the Communist Party [to be entitled to the school's official support]. Clearly, Justice Stevens does not equate faith clubs with the Klan or Communism. The thrust of his comments is to demonstrate the folly of so construing the Equal Access Act.

10 The summoning idea in the dissent of Justice Stevens is to defer to teachers, schools, and school districts in matters even quasi-pedagogical, rather than to Congress, especially where it is not clear that Congress intended that permitting any noncurricular clubs made all clubs thereafter constitutionally entitled to official recognition. As to religious student gatherings, Christian or otherwise, Justice Stevens sees nothing that prevents students from gathering to talk about their faith.

11 494 U.S. 872 (1990). www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/historics/USSC_CR_0494_0872_ZS.html

12 374 U.S. 398 (1963). Sherbert involved a devout Seventh-day Adventist woman denied unemployment benefits after she was jobless because she would not work on her Saturday Sabbath. The rule established by the Supreme Court was that governmental actions substantially burdening religious practice must be justified by a "compelling governmental interest," else the burden will require an exemption. The Smith case limited Sherbert's heightened protection to select situations, including unemployment compensation benefits cases. It should be noted, however, that the strict scrutiny of Sherbert before Smith was described by some as "strict in theory but feeble in fact." Justice Stevens also wrote that "granting unemployment benefits is necessary to protect religious observers against unequal treatment" (concurring in Hobbie v. Unemployment Appeals Comm'n of Florida, 480 U.S. 136 [1987]. www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/historics/USSC_CR_0480_0136_ZC1.html).

13 Christopher L. Eisgruber, The Next Justice: Repairing the Supreme Court Appointments Process (Princeton University Press, 2007). Fordham L. Rev. 74 (2006): 2177. http://law2.fordham.edu/publications/articles/500flspub10761.pdf

14 Eduardo M. Peñalver, "Treating Religion as Speech: The Religion Clause Jurisprudence of Justice Stevens," Fordham Law Legal Studies Research Paper, No. 99 (November 2005).

15 Id., referencing an article by Douglas Laycock in DePaul L. Rev., 39, p.1010. See also Robert Marus, "Church-state advocates urge strong successor for Stevens" (April 9, 2010), http://www.abpnews.com/content/view/5032/97/

16 newsweek.washingtonpost.com/onfaith/georgetown/2010/04/the_religious_

neutrality_of_justice_stevens.html

17 www.abpnews.com/content/view/5032/97/

18 John Paul Stevens and the Constitution: The Search for Balance (University Park, Pa.: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1988), p. 47.

Article Author: David A. Pendleton

David A. Pendleton has served as a schoolteacher, college instructor, trial lawyer elected state legislator, and policy advisor to a state governor, and now adjudicates workers' compensation appeals in Honolulu, Hawaii.