Justifying Liberty

Philip Bigler and Annie Lorsbach July/August 2016With independence from Great Britain finally secured through the ratification of the Treaty of Paris in 1783, domestic concerns once again became more prominent. Many Virginians were appalled by what was generally perceived to be a lack of civic virtue among their citizens. There was a widespread consensus that this problem was caused by the growing secularization of society and the resulting moral laxity. To compensate, a seemingly minor and innocuous piece of legislation was introduced in the state legislature to authorize the government to financially support “teachers of the Christian religion.”

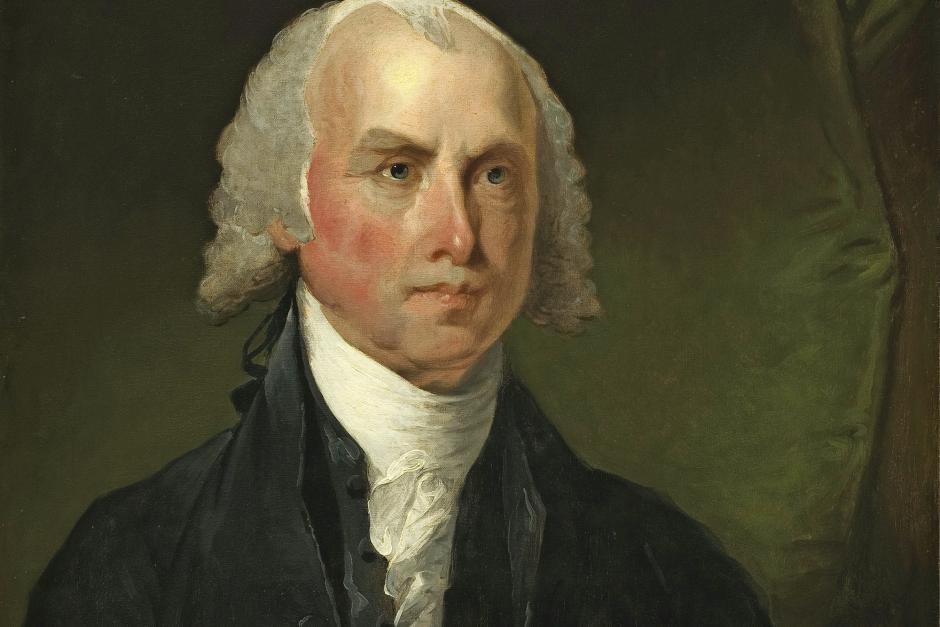

The bill was well intentioned, outwardly benign, and enjoyed the strong support of Patrick Henry. It seemed predestined to be enacted into law without either much discussion or debate. For James Madison, though, the legislation was a violation of the fundamental principle of religious freedom that had been codified in the Virginia Declaration of Rights. Madison believed that no one should be compelled by a secular or ecclesiastical power to support any religious theology.

Left unchallenged, the law would establish a dangerous precedent that would allow the government to intrude at will into what were essentially matters of personal belief. The potential for future mischief was great, Madison warned. “It is proper to take alarm at the first experiment I our liberties. . . . The freemen of America did not wait till usurped power had strengthened itself by exercise. . . . They saw all the consequences in the principle, and they avoided the consequences by denying the principle. We revere this lesson too much, soon to forget it.”1 Madison found a willing and able ally in his old mentor, the curmudgeonly George Mason of Gunston Hall. Mason not only agreed philosophically, but also had a general aversion to all forms of taxation.2

During this critical time Madison remained in frequent correspondence with his good friend Thomas Jefferson, who was serving abroad as American minister to France. Jefferson, an equally outspoken advocate of the separation of church and state, was predictably outraged that the battle for freedom of conscience had to be waged once again. In a private letter to Madison, Jefferson offered a surprisingly candid appraisal of the situation, blaming Patrick Henry for causing the political morass.

“While Mr. Henry lives another bad constitution would be formed, and saddled for ever on us. What we have to do I think is devoutly to pray for his death, in the mean time to keep alive the idea that the present is but an ordinance and prepare the minds of the young men. I am glad the Episcopalians have again shown their teeth and fangs. The dissenters had almost forgotten them.”3

Despite Jefferson’s peculiar desire that Henry be removed from the state legislature by divine intervention, the far more pragmatic Madison orchestrated an equally effective, albeit more subtle, scheme to reduce Henry’s influence within the state. Through clandestine maneuvering, Madison helped elect Henry governor and thus removed the great orator from the debates in the state legislature. Henry proudly assumed his new office, leaving the assessment legislation in hands less able to manage the growing opposition from the Baptists and other religious minorities.

In an era when communication was primitive, letter-writing expensive, and information undependable, the most effective way for citizens to seek redress for their grievances was through formal petition.4 Madison wrote and circulated what became known as “Memorial and Remonstrance” for the citizens of Orange Country, although he would not publicly acknowledge authorship for decades. Ultimately 15 of these petitions protesting the plan for government funding for religious teachers circulated throughout the state and garnered an impressive 1,552 signatures.5

“Memorial and Remonstrance” remains the single-greatest justification for religious liberty in American history. The logic contained within the document is unassailable, and Madison’s arguments are persuasive and eloquent. He steadfastly maintained that the way a person chooses to worship God was a matter of personal conscience and could be “directed only by reason and conviction.”6 Thus, any effort by a government to either sanction or prohibit religious beliefs was, in fact, an essential act of tyranny.

The memorial further asserted that individuals had a fundamental right not to believe in any theology and could not be compelled to accept the legitimacy of a given church. Individuals could not be forced to tithe or financially support any religious denomination that they did not voluntarily accept as true.

“Whilst we assert for ourselves a freedom to embrace, to profess and to observe the Religion which we believe to be of divine origin, we cannot deny an equal freedom to those whose minds have not yet yielded to the evidence which has convinced us. If this freedom be abused, it is an offense against God, not against man: To God, therefore, not to man, must an account of it be rendered.”7

Thomas Jefferson had offered a similar assessment in his Notes on the State of Virginia, claiming that a person’s religious beliefs were wholly outside of the public forum. “But it does me no injury for my neighbor to say there are twenty gods, or no god. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg.”8

The “Memorial and Remonstrance” consisted of 15 paragraphs and concluded with a firm statement.

“We the Subscribers say, that the General Assembly of this Commonwealth have no such authority: And that no effort may be omitted on our part against so dangerous an usurpation, we oppose to it, this remonstrance; earnestly praying, as we are in duty bound, that the Supreme Lawgiver of the Universe, by illuminating those to whom it is addressed, may on the one hand, turn their Councils from every act which would affront his holy prerogative, or violate the trust committed to them: and on the other, guide them into every measure which may be worthy of his blessing, may redound to their own praise, and may establish more firmly the liberties, the prosperity and the happiness of the Commonwealth.”9

Through Madison’s efforts the assessment bill was voted down in the legislature, and its defeat provided the opportunity to resurrect Thomas Jefferson’s Statute for Religious Freedom, which had been tabled since 1779. The legislation passed the General Assembly quickly, and James Madison proudly informed Jefferson, “I flatter myself [we] have in this Country extinguished for ever the ambitious hope of making laws for the human mind.”10 These same sentiments would be later codified into federal law with the adoption of the First Amendment to the Constitution in 1791.

To Madison, Jefferson, and the other founders, religion was an intensely personal matter. Although secular government had no role in supporting or advancing religion, Madison felt that it was “essential to the moral order of the World and to the happiness of man.”11 Moreover, in a letter written in 1822, Madison maintained that “religion flourishes in greater purity, without than with the aid of Govt.”12 Through Madison’s efforts, religious liberty in the United States is a fundamental right, and the way, whether, and how one chooses to worship God is essentially an act of faith, a personal choice, and not one of statute.

An excerpt from Philip Bigler and Annie Lorsbach, Liberty and Learning: the Essential James Madison (Harrisonburg, Va.: 2009). James Madison Center, James Madison University.

1 James Madison, in Irving Brant, “Madison: On the Separation of Church and State,” William and Mary Quarterly 8, no. 1 (1951): 10.

2 The power to tax was seen in the colonial period as the power to destroy. The bill levied a tax equal to that of the Tea Act, which had led to the Boston Tea Party and directly to the American Revolution.

3 Thomas Jefferson to James Madison, Dec. 8, 1784.

4 The fundamental right to petition the government is codified in the First Amendment to the Constitution. Although this may today seem anachronistic, it was an important guarantee in the eighteenth century.

5 Robert A. Rutland, ed., The Papers of James Madison: 10 March 1784-28 March 1786 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973),p. 297.

6 Madison’s “Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessment’s” is available at ttp://etext.lib.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/MadMemo.html.

7 Ibid.

8 Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia, available at http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/JefVirg.html.

9 “Memorial and Remonstrance”

10 James Madison to Thomas Jefferson, Jan. 22, 1786.

11 James Madison to Frederick Beasley, Nov. 20,1825.

12 James Madison to Edward Livingston, July 10, 1822.

Article Author: Philip Bigler and Annie Lorsbach

An excerpt from Philip Bigler and Annie Lorsbach, Liberty and Learning: the Essential James Madison (Harrisonburg, VA: James Madison Center, James Madison University, 2009).