Leaving Faith Behind

Kevin D. Paulson November/December 2011

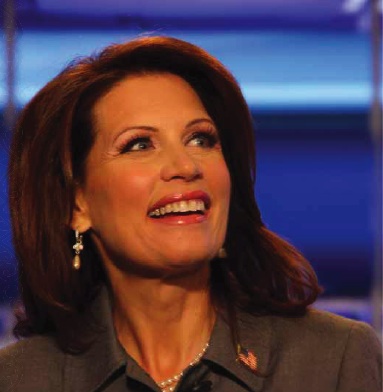

On July 15, 2011, with political headlines dominated by negotiations over the U.S. debt ceiling, another political story caught the nation’s notice. At the top of CNN’s political page that day, the story read, “Michele Bachmann Officially Leaves Her Church.”1

According to the report, the Bachmanns—members of the Salem Lutheran Church in Stillwater, Minnesota, for the previous 10 years—had asked to be released from their church membership on June 21, 2011, a scant six days before Congresswoman Michele Bachmann (R-Minn.) announced her candidacy for the presidency of the United States.

The report went on to explain the reason for the Bachmanns’ departure from this particular church—the fact that the Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod (of which the Salem Lutheran Church is a constituent part) identifies the Roman Catholic Church Papacy as the antichrist of Bible prophecy. The denomination’s Web site declares, “This is an historical judgment based on Scripture.”2

Presidential candidate Michele Bachman.

Presidential candidate Michele Bachman.

Conviction or Convenience?

As Americans, the Bachmanns certainly have the right—as do all citizens—to associate with or withdraw themselves from any group or ideology, for any or no reason. But one can’t help wondering, if their former denomination’s views on Catholicism were openly posted on the church’s Web site, why it took them so long to decide to leave. Are they leaving because they think the teachings of their former church contradict the Bible on this point? Do they hold that these teachings constitute “anti-Catholic bigotry”? If so, when did they decide this? And why did they choose to leave but a few days before Michele Bachmann announced her candidacy for the presidency?

In short, was this a decision based on religious conviction, or political convenience?

Conservative Politics and the New Ecumenism

The CNN article in question went on to trace the historical roots of Protestant beliefs regarding the Roman Papacy, in particular Martin Luther’s use of the term antichrist to describe the Catholic system on account of its conflict with what Luther held to be key features of the New Testament gospel.3 The fact that Roman Catholics dismiss such views as bigotry was also noted in the article.4

Since the emergence of the Religious Right on the American political scene in the late 1970s and early 1980s, cooperation between Protestants and Catholics for political purposes has been both open and active. Such religio-political alliances have also existed, of course, in the context of liberal causes (e.g., civil rights, the Vietnam War), though the corporate nature of these and similar moral issues made religious involvement less problematic for the separation of church and state, at least in many minds. Within the setting of the Religious Right, many trace the culmination of such harmony to the 1994 document “Evangelicals and Catholics Together,”5 which proclaimed a new Christian unity relative to both theological and political goals. The document was prepared and endorsed by such prominent Catholic thought leaders as Richard John Neuhaus and George Weigel, and by such Protestant luminaries as former Nixon aide Charles Colson and televangelist Pat Robertson.6

What I have chosen to call the “new ecumenism” is significant because of its differences from the old ecumenism. When many conservative Christians think of the ecumenical movement, they think of such organizations as the National and World Councils of Churches, or of meetings at which doctrinal compromises are crafted for the sake of denominational mergers—often by theological liberals with nontranscendent, less-than-absolute views of biblical authority. For this reason the very phrase “ecumenical movement” has long evoked negative responses from the conservative wing of Protestantism. And yet, with the rise of the Religious Right, it has been these very conservative Protestants that have been most proactive in forging unity with Roman Catholics for political purposes. Rather than seeking unity through some doctrinal “middle ground,” achieved through the give-and-take of dialogue and negotiation, the new ecumenism simply ignores doctrinal differences—even major ones—for the sake of a united front against what is held to be a permissive, morally bankrupt culture at odds with a wide range of religious and conservative cultural beliefs.

The Problem

But expedient unity of this sort carries with it a major problem.

Adherence to moral absolutes is a cornerstone of conservative Christianity. For Protestants, historically, this has meant holding to the Bible as the exclusive guide to faith and practice—sola scriptura, as the Reformers said. On this basis, conservative evangelicals condemn fornication, adultery, homosexual practice, the production and viewing of pornography, and other practices considered to be immoral and sinful.

The challenge arises when the same Bible that condemns practices generally viewed by conservative Christians as morally wrong is also found to condemn beliefs and religious practices held dear by a large segment of the “moral majority” thus built. This problem, when considered, poses some serious questions for those with a high view of biblical authority. If the Bible is truly the source of the moral convictions by which one measures society, on what basis does one refuse to apply the biblical standard to political allies whose teachings or religious practices contradict the Bible? If one chooses simply to ignore such contradictions, what is to be made of the biblical command not to be “unequally yoked together with unbelievers” (2 Corinthians 6:14)? In short, what happens when, for the Christian seeking to blend biblical teachings with a political agenda, biblical absolutes become politically inconvenient?

Perhaps the Bachmanns will say they left their former church because they disagree with what many are pleased to call the “anti-Catholic bigotry” of its position on the Papacy. If so, what guides the Bachmanns’ definition of bigotry? The Bible? Popular opinion? Many, after all, would describe the Bachmanns’ stand on homosexual practice as bigoted. If the Bible is their authority on moral issues despite accusations of bigotry, what about theological issues? If the Bible is truly God’s infallible Word, shouldn’t its adherents stand by all of its teachings, even if others call such teachings bigoted? If the Bachmanns are prepared to do this regarding the issue of homosexuality, why not regarding their church’s stand on Catholicism? Again, if they believe their church’s stand in this regard is unscriptural, why did it take them 10 years to figure this out? And why did they decide to sever their connection with this church only as Michele Bachmann was about to announce her run for president?

The Bottom Line

This, at the bottom line, is why politics is such a dangerous means by which to advance the church’s mission, and it offers yet another reason that the separation of church and state is an imperative for the church as well as the government.

In the world of politics, success is defined by 50 percent plus 1. In the biblical worldview, by contrast, success is defined exclusively by faithfulness to the divine Word, regardless of how inconvenient or unpopular such faithfulness might be. In the pursuit of politics one is obligated to please the majority; in the preaching of the gospel one is obligated only to please God. When the so-called Moral Majority first came on the American scene, many Christians (as well as others) found the name unsettling. After all, the Bible never promises that God’s true followers will ever comprise a majority, even among professing Christians. Jesus Himself declared, “Narrow is the way which leadeth unto life, and few there be that find it” (Matthew 7:14). According to the Bible, only eight people got on board Noah’s ark (Genesis 7:7; 1 Peter 3:20); only three stood unmoved when the rest of the world bowed before Nebuchadnezzar’s image (Daniel 3:12). And at the end of human history, according to the Bible, those found faithful are described, not as a majority, but as a remnant (Revelation 12:17).

According to Scripture, the Christian’s duty is to adhere to the counsel of God, even if the result is revilement and ridicule by the rest of society. Biblical teachings cover more than sexuality issues. They place in the crosshairs of scrutiny a wide range of cherished beliefs and practices, including many held dear by conservative Christians. Something is very wrong with the spiritual integrity of church members who are prepared to sacrifice biblical teachings for the sake of political objectives. Such dilemmas, however, become inevitable when Christians seek to blend the church’s agenda with that of the state. Majority opinion is the guiding force in representative government, and when the biblical message is subjected to such a standard, much of it will be lost. And with it, the most basic authority of the Christian faith itself.

1 Eric Marrapodi, “Michele Bachmann Officially Leaves Her Church,” http://religion.blogs.cnn.com/2011/07/15/michele-bachmann-officially-leaves-her-church.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 “Evangelicals and Catholics Together: The Christian Mission in the Third Millennium,” First Things, May 1994, pp. 15-22.

6 Ibid.

Article Author: Kevin D. Paulson

Kevin Paulson is a much-published author, editor, and minister of religion. He writes from Berrien Springs, Michigan.