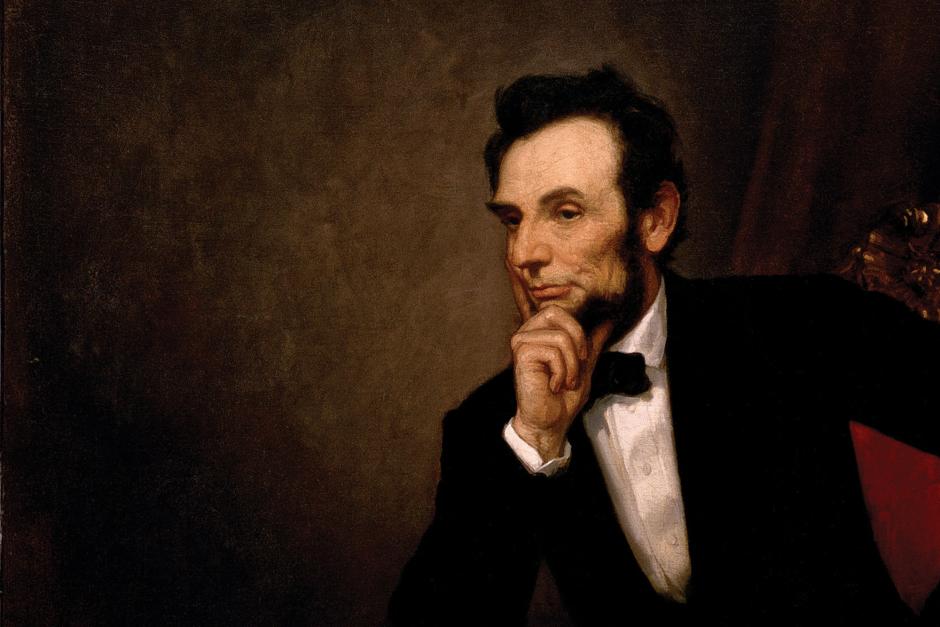

Lincoln’s Noble Character

Haven Bradford Gow January/February 2013Temple University historian Gregory Urwin, in his contribution to Lincoln and Leadership (Fordham University Press), observes: "recent surveys reveal that most American historians continue to rate Abraham Lincoln as the country's best president. This subjective judgment hinges primarily on Lincoln's performance as commander in chief in the Civil War, in which he surmounted a host of daunting challenges and succeeding in both preserving the Union and destroying slavery." Urwin refers to Lincoln as "the greatest war president in American history. . . . He bore the burden of leading his people through an agonizing ordeal, and he attempted to bind the nation's wounds even before the guns fell silent."

Lincoln also displayed nobility of mind, spirit, and character by his courageous opposition to the extension of slavery and to the United States Supreme Court's Dred Scott ruling, that denied equal rights and personhood to Black people. Benjamin Tyree, a Washington, D.C., journalist, says Lincoln firmly believed in the statement that "all men are created equal," and that "he referred to this cornerstone of the Declaration of Independence as the central idea of the nation, and a part of its actual law as well as its emotional history. On this, finally, hung the moral justification of the Union's crusade to force the South back into the Union, together with the concept of civic virtue embodied in the Union and in its Constitution." He adds that "from the beginning, Lincoln was determined to fight the attempt, which was built upon the foundation of human rights."

According to journalist Rogert Shogan, author of The Double-edged Sword: How Character Makes and Ruins Presidents, from Washington to Clinton (Westview Press), President Lincoln's greatest test of character involved the explosive issue of slavery. For Lincoln, slavery was a vicious and obscene violation of God-given human rights and of the proposition of our founders that "all men are created equal." And that is why Lincoln commanded the North to wage war with the South, and why he also issued his Emancipation Proclamation.

Mr. Shogan rightly credits Lincoln's nobility of character for his courageous opposition to slavery; he observes: "to a degree, this was . . . a journey of the mind. But it also represented a development of character without which Lincoln's intellect could not have made the leap from defense of the past to staking out a new vision for the Republic, which would become the legacy of his character to his country and his successors."

Certainly we desperately need today many more men and women of Abraham Lincoln's nobility of mind, spirit, and character.