Love Those Reformers

Michael D. Peabody November/December 2017Agape love is the central premise of Protestant Christian theology. According to The Oxford Handbook of Theological Ethics, “Luther’s rediscovery of the primacy of agape was the linchpin of the Reformation and the rediscovery of genuine Christian ethics.”1

Many confuse the concept of agape love with the concept of caritas, or charity, but these are two separate ideas. Agape love is the love of God reaching down to save humanity through grace, while caritas is about humans reaching upward toward God through works.

The Greeks

In Greek philosophy the gods were distanced from humanity because the gods must remain absolutely perfect. If they even had knowledge of humans and their imperfections, it could corrupt them. So the Greeks believed that the primary god (the apriori divine origin of the soul), to remain perfect, had set the universe in motion and completely forgot about earth, so that god would have no knowledge of evil. Knowledge of evil would corrupt the perfection of this god, and because this god was stationary and unknowable, humanity could only ascend upward. Despite the distance, the Greeks reasoned, the soul had a natural affinity for its divine home, and Plato (428-347 B.C.) called this longing “heavenly eros.” They believed that because the soul had its origin in god, humans were basically good by nature. They could fulfill their natural affinity for god by doing good works, or caritas, sacrifices, and devotion with the goal of advancing to more of a godlike state upon reincarnation. The passionate desire for god that made people want to escape the earth and ascend directly to god was called heavenly eros. Plato philosophized that in this state all motivation would be free of the hindrances of the material world and the soul would be perfected through intellectual contemplation.

Ascending through reincarnation could be accomplished through good works, sacrifices, and religious devotion. At the highest level of heavenly eros, Plato philosophized that all motivation would be free of the hindrances of the material world and that the soul could be perfected through intellectual contemplation.

The Greeks believed the highest expression of eros on earth would be if one were willing to sacrifice life itself for his or her friends, and they illustrated this love through the fable of the good king Admetus and his wife, Alcestis.

In the story, Admetus was told that he would die and that he could survive only if a virtuous man or woman would take his place. So he went to his elderly parents, who felt sorry for him but who refused to die because they loved their own lives more than they loved him. His brothers and sisters similarly declined. Even a sick person at the brink of death refused.

Finally, Admetus’ wife, Alcestis, agreed to die for him. She cried out to the god Apollo that the people needed such a good king. So she sacrificed herself for Admetus, and in pity the gods gave her a new life.2

The Early Church

For the Greeks, dying for one’s friends was the ultimate expression of love, but the Christian belief that the Son of God died for His human enemies went way further in explaining the outer reaches of agape love.

In sharp contrast to the Greek belief that the best that humanity can achieve is a shadow of divine perfection, and that the divine could not know human imperfection, not only does the Christian God have knowledge of sin, but God Himself became “sin for us, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God” (2 Corinthians 5:21, NIV).3 Instead of exacting revenge for the painful crucifixion, in the midst of the execution Jesus called for divine forgiveness: “Father, forgive them; for they know not what they do” (Luke 23:34).

The Christian belief that God would have full knowledge of humanity was completely foreign to Greek thought and must have seemed delusional. Paul wrote that the Christian doctrine of God descending to become an actual human was foolishness to the Greeks and offensive to the Jewish people (see 1 Corinthians 1:21-23).

In contrast to Greek thought, in Christian thought God is not unknowable, but is seeking to directly relate to human beings. “I stand at the door and knock. If anyone hears my voice and opens the door, I will come in and eat with that person, and they with me” (Revelation 3:20, NIV).

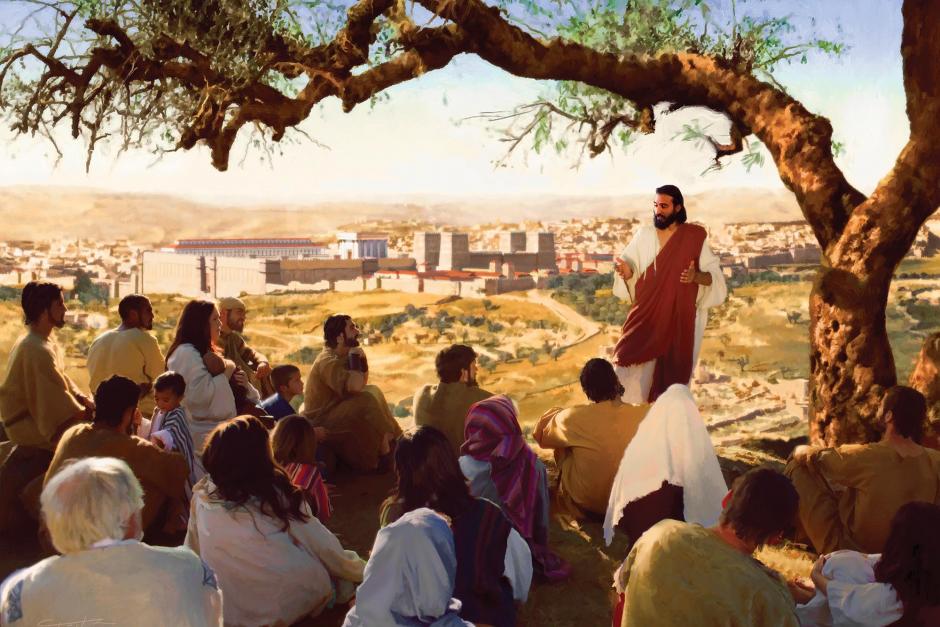

Jesus called His followers to a vastly deeper love than the eros described by the Greeks. In Matthew 5:44 Jesus calls His followers to “love your enemies.” This was not simply a pithy aphorism but a commandment.

In a larger context Jesus contrasts this command with the teachings of the time. “You have heard that it was said, ‘Love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I tell you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, that you may be children of your Father in heaven. He causes the sun to rise on the evil and the good, and sends rain on the righteous and the unrighteous. If you love those who love you, what reward will you get? Are not even the tax collectors doing that?” (Matthew 5:43-46, NIV).

The revolutionary idea that God would seek to have a relationship with humanity is the foundational concept of New Testament theology. In reflection on Christ, the early church would periodically have what they called “agape meals” to commemorate the Eucharist or self-sacrificing descent of God to humanity and His subsequent divine invitation to participate with Him in the Resurrection and Ascension.

Christian Thought Merges With Greek Thought

Three centuries after the Ascension,Augustine of Hippo, well versed in both Greek philosophy and Christianity, began to wed the concepts of both Christian and Greek thought. While Augustine believed that God could know humans, he also adopted the Greek concept that in order for the soul to ascend upward, it must be purified through good works. The grace of God alone was not sufficient—one must do something to earn salvation.

Augustine postulated that good works should be done, not only because they were good in the agape sense, but because humans would benefit by obtaining the reward of eternal life. In developing this hybrid, Augustine took the Platonic concept of heavenly eros, merged it with the Christian concept of agape love, and called the result caritas, or charity. Lutheran theologian Anders Nygren wrote extensively on this development in his book Eros and Agape, published in 1930 and 1936.

According to Nygren, caritas is intended to acquire and possess, and is a needs-based and desire-based, egocentric and acquisitive love. In contrast, Nygren describes agape love as spontaneous, unconditional, centered on God (theocentric), self-giving, and self-sacrificial. Agape leads a person to surrender love to another and love them purely for themselves.4

Augustine believed that humans could work their way back to God and that God’s mercy would be in the form of the person’s desire to do good to accomplish this task.

By contrast, the Bible consistently says all are sinners, and even Paul, who focused his early career on persecuting Christians before his conversion, would be saved. “Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners; of whom I am chief” (1 Timothy 1:15).

To answer the question of how sinners could be saved, and relying heavily on Augustine, the Roman Catholic Church developed the concept of purgatory, a temporary form of hell for those who die in friendship with God but are still not perfected. Humans who are not perfect on death can be purified through purgatory and then brought up to God.

Through Augustine’s influence, the church began to teach that salvation was connected with works for those who wanted to avoid eternal torment and minimize their experience in purgatory. They believed that salvation was something a person could earn, not based on unmerited favor, but instead by relying on external acts of piety such as traveling long distances to see the relics of saints, participating in warfare during the Crusades, or even purchasing “indulgences” to reduce time in purgatory.

Because salvation could be granted by the church based on outward acts rather than an internal acceptance of grace, Augustine, one of the early Church Fathers, saw value in forcing somebody against their will into the state of salvation.

Augustine wrote that although it was preferable that a person come to worship God through teaching, it was not the only way to bring about salvation. Torture, involving fear and pain, could be applied for the benefit of the victim.

“It is indeed better (as no one ever could deny) that men should be led to worship God by teaching, than that they should be driven to it by fear of punishment or pain; but it does not follow that because the former course produces the better men, therefore those who do not yield to it should be neglected. For many have found advantage (as we have proved, and are daily proving by actual experiment), in being first compelled by fear or pain, so that they might afterwards be influenced by teaching, or might follow out in act what they had already learned in word.”5

Ultimately the medieval church, because of a caritas-based love for the eternal soul, reasoned that it was better to force somebody to change their mind on faith than let them go to hell. Torture mechanisms were designed to keep people alive for as long as possible to provide more opportunity for their salvation as they writhed in agony.

In 1510 Martin Luther was climbing the Scala Sancta (or Holy Stairs) on his knees. He had tried many things to earn the forgiveness of God and continually felt he fell far short and would be sent to hell or a lengthy torment in purgatory. According to Reformation lore, as he climbed, he was struck by the words of Romans 1:17 that “the just shall live by faith.”

Luther began to preach what he had discovered during his biblical research—that humans are justified by the grace of God and that salvation is entirely outside of human effort. The righteousness of Christ was credited to humans through faith. Luther taught that the only love humans could really generate was egocentric love, which is, at its best, charity. The love revealed in Christ, agape, was something far greater—the love that gives.

Luther taught that humans did not need the church, a pope, or an emperor to declare them eternally saved. Because Luther’s writings led to the reformation of the issue of justification, Nygren has written that Luther was also “the reformer of the Christian idea of love.”6

Nygren continues: “In Augustine, the issue between Eros and Agape is decided in favour of synthesis; in Luther, in favor of reformation. Augustine unites two motifs in the Caritas-synthesis; Luther shatters that synthesis.”7

In recent years some have argued that the Reformation is over because of the Catholic modifications in the Council of Trent; however, the core dispute of the Reformation remains. In Catholic theology God looks at a person to determine whether they are righteous enough to be saved. If not, they are sent to purgatory for an extended period of time so they can merit their salvation, or sent straight to hell. In Protestant theology a person is saved through the grace of God, not for further punishment, but to be saved eternally or to be lost eternally.

Agape, Caritas, and Government

Although the concept of agape love is at home within Christian theology, it does not translate easily to civil government. Government, even Christian-based government, cannot truly express agape love. A civil government is bound by concepts of fairness and the equal protection of the law. Granting unmerited grace to a criminal to the point of not punishing or demanding restitution, for instance, may not be in the best interest of the victim, much less the society as a whole.

Civil governments that attempt to form themselves after a theological construct almost invariably tend to abandon any semblance of agape grace and begin to impose harsh penalties on religious dissidents.

Christian theocracies are no different. John Calvin (1509-1564) tried to create a sin-free environment in Geneva and was unsuccessful in imposing this theocracy on the people. According to J. B. Galiffé, never before did immorality take hold and spread as it did in the period of Calvin’s government.8

Calvin’s Geneva arose in the shadow of the Inquisition, and even Protestants adopted the same torture methods. For instance, Protestants in England persecuted their own religious dissidents, who were hung, drawn and quartered, and tied to posts in the oceans and left to drown as the tide came in.

Even Luther, whose grace-based theology reintroduced the concepts of agape love, nearly lost his way in his graceless diatribes against the Jews and his support of the brutal suppression of the peasants who revolted against princes who had protected him.

Although early Protestantism failed to implement systems that embraced the concept of agape love, it eventually began to take hold of Protestant thought and finally found expression in the New World.

Despite a flawed history, the United States is one of the few nations in the world that jointly accepts the grace-based foundation of Protestantism and the caritas-based rule of law. This is expressed in the separation of church and state, which recognizes the value of each in its separate sphere of influence. It is a generous nation that does not seek to interpose itself between the citizen and his or her faith. It is a generosity made in the spirit of the Reformation.

1 G. Meilaender and W. Werpehowski, The Oxford Handbook of Theological Ethics, (2007), p. 456.

2 See Thomas Bulfinch, The Age of Fable: Vols. I and II: Stories of Gods and Heroes (1913).

3 Bible texts credited to NIV are from the Holy Bible, New International Version. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

4 See Alan Vincellete, “Introduction,” in Pierre Rousselot, The Problem of Love in the Middle Ages: A Historical Contribution (Milwaukee, Wisc.: Marquette University Press, 1998), p. 111.

5 Augustine, “The Writings Against the Manichaeans and Against the Donatists,” available at http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf104.v.vi.viii.html.

6 Anders Nygren, Eros and Agape (1930, 1936), p. 683.

7 Nygren, p. 692. See also Werner G. Jeanrond, A Theology of Love (2010), pp. 117, 118.

8 See J. B. Galiffé, Nouvelles pages d’histoire exact, pp. 95-98.

Article Author: Michael D. Peabody

Michael D. Peabody is an attorney in Los Angeles, California. He has practiced in the fields of workers compensation and employment law, including workplace discrimination and wrongful termination. He is a frequent contributor to Liberty magazine and editsReligiousLiberty.TV, an independent website dedicated to celebrating liberty of conscience. Mr. Peabody is a favorite guest on Liberty’s weekly radio show, “Lifequest Liberty.”