No Abaya for McSally

John W. Whitehead July/August 2002

By John W. Whitehead

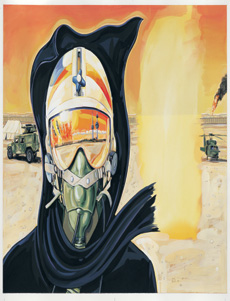

Illustration by James Mellett

When Lt. Col. Martha McSally takes to the skies, she is the embodiment of a modern-day hero: courageous, selfless, and loyal to God and country.

She is a patriot who has willingly put her life on the line to protect American interests abroad-a perfect example of how far women have come in their fight for equality.

Yet even these notable distinctions were not enough to afford her the basic respect and treatment given to her male colleagues in Saudi Arabia. In fact, because she is a woman, when off the base McSally was required by U.S. military policy to wear the traditional Muslim abaya-a black head-to-toe robe and head cover worn in certain Muslim cultures and perceived as a sign of subordination to men. This is in spite of her religious objections-McSally is a Christian-and her repeated requests that she be allowed to wear appropriate American clothing, as her male counterparts do. The policy, which applies to all female joint operations military personnel in the U.S. Armed Forces in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia-about 1,000 servicewomen in all-

Neither the U.S. State Department nor the government of Saudi Arabia actually requires American service members to wear traditional Muslim attire for any reason. In fact, the Saudis do not require non-Muslim women to wear the abaya at all. And servicemen are actually prohibited from wearing traditional male Muslim clothing while off base. Indeed, the regulation requiring Lt. Col. McSally to wear the abaya is a peculiarly American rule.

Furthermore, although Islamic values and cultures in other countries such as Kuwait, Pakistan, and Afghanistan are as strong as they are in Saudi Arabia, the military has yet to place similar restrictions on female military personnel stationed in those, or any other, countries.

Considering the fact that our host country does not even insist on such measures, the military's insistence that the established dress code gives greater respect to the religious and cultural customs of the community, that it avoids public conflict, and that it aids the U.S. military in carrying out its mission simply does not comport with reality. Especially when considered in the context of the war on terrorism, with the national spotlight being redirected to focus in on the plight of the Afghan women, McSally's humiliating situation seems even more incomprehensible and ridiculous.

Five U.S. senators evidently agreed that the regulations might violate the service members' "rights and liberties as U.S. citizens." With Bob Smith (R-N.H.) as spokesperson, Jesse Helms (R-N.C.), Don Nickles (R-Okla.), Susan Collins (R-Maine), and Larry Craig (R-Idaho) went so far as to urge Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld to do a top-level review of the policy. They also felt the policy would discourage other qualified women from enlisting in military service.

After all, at the same time that American politicians are calling for the liberation of Muslim women in Afghanistan, should we be forcing American servicewomen in Saudi Arabia to violate their constitutional rights and be treated as second-class citizens? Should a decorated military hero be forced to take on a subservient role, despite her rank, simply because she is a woman? Should a Christian, whose right to religious freedom is protected by the U.S. Constitution, be forced to adopt Islamic dress and adhere to Islamic customs just because she is protecting U.S. interests on foreign soil?

To McSally, a decorated officer who has flown 100 combat hours over Iraq and has served as flight commander and trainer for combat pilots deployed to Kosovo and South Korea, the policy seemed to contradict the very principles she and so many other brave Americans have been fighting for. That is, the right to express one's religious beliefs freely; the right not to be forced to adopt someone else's religious beliefs; the right to be treated equally; the right not to be subjected to gender discrimination.

For several years before being assigned to Saudi Arabia, McSally had been working within the system to have the dress policy for Saudi Arabia changed. And for as many years military brass promised policy reviews that never took place.

But when she was assigned to Saudi Arabia, the issue became much more personal. So McSally once again voiced her personal objections to the policy-and requested accommodation of her beliefs. Two days prior to her departure for Saudi Arabia, McSally received e-mails from military personnel threatening her with court-martial if she didn't follow the order to wear the abaya. Even before she'd set foot on Saudi soil, the U.S. military was forcing her to decide between following an order or following her conviction as an officer and a Christian. One military commander did urge her to keep working within the system-to abide by the policy long enough to get to the Saudi base, to give the military brass stationed in Saudi Arabia the chance to see her as an officer, a warrior, a fighter pilot-so that she would have a better chance of bringing about a change from the inside. So McSally flew into Prince Sultan Air Base, Saudi Arabia, only to be met by a young enlisted man, who informed her that she had to sit in the back of the vehicle and cover herself with an abaya. There it was, the middle of the night, and she was traveling from one base to another in a Suburban with dark tinted windows, with a group of American military men wearing collared shirts and jeans. Yet only Lt. Col. McSally, the highest-ranking person in the group, was forced to sit in the back seat and put on the abaya and the abaya scarf.

During the course of the 13 months that followed, there were numerous times when McSally found herself having to decide between following her faith and oath of office or following an order she believed to be unconstitutional. Time and again she made the choice to fulfill her military duty. Yet when given a chance to leave the base for R and R, always wearing the abaya and accompanied by a male, McSally chose to stand on principle, stay on base, and work toward a change in the policy.

McSally waited and waited for change. For more than six years she had tried to bring about a change to these policies from the inside.For 13 months she abided by this policy herself. And after the bidding of the five Republican senators she waited another four months for a promised policy review. Finally in December 2001 McSally decided it was time to have the third branch of the government take a look at the policy.With the help of the Rutherford Institute she decided to try to bring about a change from the outside.

"I'm a follower of Christ, and my Christian faith is the centerpiece of who I am. To be forced to put on the garment of a religion that I do not believe in and a faith I do not follow, to me, was unacceptable," shared McSally. "Second, the women whom this affects-the officers and enlisted personnel serving over there-we are putting our lives on the line to serve our nation, and we are over in Saudi Arabia as officials of the United States government and the United States military, doing a mission alongside the men.

"Wearing the abaya, sitting in the back seat, not being able to drive and having your subordinate have to claim you as his wife, as opposed to his supervisor, is so demeaning and so humiliating. To treat just some of our people in that way for reasons that I still haven't been able to get a very solid answer on is unacceptable." Within a matter of weeks after the Rutherford Institute had filed suit on behalf of McSally and had taken the media by storm, General Tommy Franks issued a new directive about the abaya. Local commanders would revise policies on wearing the full body veil from mandatory to "strongly encouraged."

Ultimately, the lawsuit against Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld comes down to several key constitutional issues. One is the freedom of religion. Lt. Col. McSally is, in effect, forced to wear a religious outfit-which the abaya is-required by Islamic law for women to wear in Saudi Arabia-and to pretend she's Islamic, which violates her religious freedom as a Christian.

The second is a course of action embraced in the terms of the once legislated and then judicially overturned (not because the principle was erroneous, but because the act gained its power over the states by improperly invoking the commerce clause) Religious Freedom Restoration Act, which says that if the government in any way violates a person's religious freedom, it has to show a compelling state interest to do so. Even if a compelling state interest can be shown, the government has to show that it is being accomplished by the least restrictive means possible.

Third is the freedom of speech. By forcing Martha McSally to wear the abaya, the military is indirectly forcing her to voice a belief that is not her own-namely, to buy into what the abaya symbolizes: that women are the property of men.

Fourth is an establishment clause concern. Because the government is purchasing the abaya as military issue and forcing women to wear it, it's establishing a religion and, thus, violating the separation of church and state.

And finally, there is freedom from gender discrimination. This military policy is obviously

With the attention of the world upon us, is the disparaging treatment of this servicewoman an example we want to set for how to respect women and those members of our Armed Forces who are placing their lives on the line to protect our freedoms?

As part of her oath of office Lt. Col. McSally pledged to "support and defend the Constitution." Thus, she believes, as does the Rutherford Institute, that the protection of the U.S. Constitution applies to all American servicemen and women, whether they are serving their country at home or abroad. Furthermore, even in service to her country, Martha McSally is first and foremost a citizen of the United States and entitled to the protections of the U.S. Constitution.

As a result of intense media coverage over the lawsuit, some further policy revisions were instituted, making it strongly recommended, rather than required, that a woman sit in the back seat and be accompanied by a male when off base. Citing these changes, attorneys for Rumsfeld filed a motion in federal court, asking that McSally's case be dismissed.

But contending that in a military environment a strongly encouraged or recommended statement by a four-star general to a young enlisted woman can easily be construed as an order, McSally and institute attorneys are pushing forward. McSally wants to know that in six months' time, someone won't come right back and make the policy mandatory again.

As McSally says from her own experience, "I've been in several situations where I was strongly encouraged to do something, and that was essentially a code word that we had all better do whatever they were talking about. So this language is troubling, because I would hope that the abaya would truly be optional, that a woman would feel free to make an informed choice as to whether she wants to wear it or not, and that nobody would be coercing her, even subtly."

It hasn't been an easy fight for freedom. Despite the support of some within the military and a great deal of public and media support from around the world, she continues to find herself on the firing line. Suddenly, because Lt. Col. McSally dared to raise the issue and say, "This is unconstitutional, it's un-American, and it's got to change," she is being told that her choices and actions in this matter are disloyal and unprofessional, that she is exuding poor leadership.

And with each new criticism comes a reairing of the same military mantra about cultural sensitivities, forced protection issues, and absolute obedience. One critic went so far as to declare that it wouldn't hurt to wear the abaya. "Well, it didn't hurt Rosa Parks to sit in the back of the bus, either," replied McSally, "but that's not the criteria we use for whether something's right or wrong." Indeed, as McSally has pointed out numerous times, would Americans support the military's claims if they were being used to justify treating Black service members like second-class citizens during apartheid in South Africa?

There are some who have criticized Martha McSally for addressing these issues during a time of war. But it is especially during times of crisis that we must rely on our government-and our government leaders-to respect and stand by the freedoms afforded us in our U.S. Constitution. Lt. Col. McSally took an oath of office to defend the Constitution-she is willing to lay down her life for it and for the freedoms embodied within it. As a loyal citizen of the United States she has a right to enjoy the same freedoms she has sworn to defend.

___________________

Constitutional attorney and author John W. Whitehead is founder and president of the Rutherford Institute, in Charlottesville, Virginia.

Article Author: John W. Whitehead

John W. Whitehead, founder and president of the Rutherford Foundation, writes from Charlottesville, Virginia.