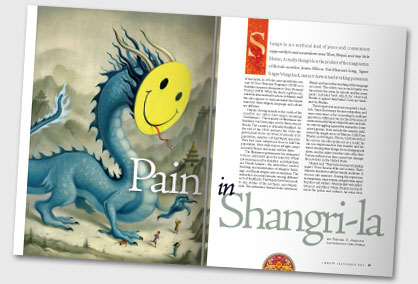

Pain in Shangri-la

Reuel S. Amdur July/August 2012

Shangri-la is a mythical land of peace and contentment supposedly found somewhere near Tibet, Nepal, and tiny little Bhutan. Actually Shangri-la is the product of the imagination of British novelist James Hilton. But Bhutan’s king, Jigme Singye Wangchuck, seems to have aimed at taking possession of that myth. In 1972 he came up with the concept of Gross National Happiness (GNH) as a Buddhist-inspired alternative to Gross National Product (GNP). While the idea has gotten considerable international traction, in Bhutan itself the idea appears to have excluded the Nepali minority: their religion, language, and culture are different.

Nepalis (living mainly in the south of the country) are called Lhotsampa, meaning “Southerners.” The majority of Bhutanese are Buddhist, but Lhotsampa are for the most part Hindu. The country is officially Buddhist. At the end of the 1980s and into the 1990s the government drove out about 20 percent of its population, members of that Nepali minority. They had once comprised close to half the population. Most ended up in refugee camps in nearby Nepal, and many still live there.

The Bhutanese government has attempted to force conformity upon the minority. While not everyone must be Buddhist, and while there are Hindu temples, the authorities control building and maintenance of religious buildings, and Hindu temples take second place. The authorities also play favorites among different sects of Buddhism. The Nepalis have been made to don clothes of the northern, non-Nepali, style. The authorities burned books written in Nepali and barred the teaching of the language in school. The oldest son in each family was forced into the army. In schools and the army, meals included beef, which for observant Hindus is against their belief. Cows are venerated by Hindus.

These repressive measures inspired a backlash. Some Lhotsampa became outspoken, and some even went so far as moving to militant opposition. Militancy was in the air because of events in nearby Nepal, where Maoists and others were struggling against the monarchy. Some armed groups, from outside the country, infiltrated the jungle areas of Bhutan. Dilli Ram Dhakal, now living in Ottawa, told Liberty that his son was one who spoke out. As a result, his son was imprisoned for four months and tortured. Among other things, he was hung upside down, and his jailers beat the soles of his feet. Torture inflicted on him caused eye damage. He now lives in the United States.

Dhakal said, “They took away my citizenship papers.” It was because of his son’s actions. That’s when he decided to take his family and leave. It was not safe anymore. During the repression and expulsion, some women and girls were raped by police and soldiers. Many people were jailed, tortured, and killed. While Dhakal has harsh words for police and soldiers, he notes that “ordinary Bhutanese were never a problem.”

Santa Maya Gurung and her 21-year-old daughter, Pabi, are another refugee family who ended up in Ottawa, Canada. Gurung left Bhutan because the army burned down her house and that of her mother. Her husband died of tuberculosis in the refugee camp. Stories like those of the two Ottawa families are not untypical.

What is the official Bhutanese position on the refugees? Prime Minister Jigme Thinley told al-Jazeera that they were illegal immigrants. However, many of the families go back a number of generations, often back to the 1800s. Dhakal thinks his ancestors came to Bhutan about 400 years ago. Bhutan has tried to claim that the Lhotsampa came in the 1970s to work on a hydroelectric project. This is clearly not the case for most of them. Many Lhotsampa are farmers, as were the Dhakals and the family of Santa Maya Gurung. Some Nepalis and others did enter the country illegally, but by far the largest numbers of those expelled were long-standing Bhutanese citizens.

Ramchandra Adhi Kari, a recent arrival in Ottawa, described conditions in the camps, which are supported by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). “The food,” he said, “is neither adequate nor nutritious.” The water is of doubtful quality. Because of serious overcrowding, disease spreads quickly. In two of the crowded camps, large numbers of houses were destroyed by fire. Poor construction and thatched roofs multiplied the damage. Sixteen-year-old Tkaram Garung arrived in Canada a few weeks before the interview. In his class in the camp there were 58 students. Classes go up through grade 12, and some people are able to get a bachelor’s degree. But because the refugees are not Nepali citizens, they miss out on the good jobs, and they can’t buy a house. Yet the refugees include people who were mayors, village leaders, doctors, engineers, and teachers.

The UNHCR and the International Organization for Migration are actively assisting in resettlement of the refugees. With close to 35,000 settled in the United States as of January 15, 2011, it is expected that the country will receive another 25,000. Canada had taken in 2,400 by then, with prospects of the total going to 10,000. Four other countries have pledged to take as many again. Outside Nepal, there are perhaps another 30,000 living unregistered in India.

Refugees who have resettled seem to have adjusted well, studying and learning the local language and finding work. Many had already studied English back in Bhutan and in the camps. Dhakal’s son Chabi is an example of success. Back in the camp, he excelled in school to such an extent that he was admitted to a Nepali boarding school. Coming to Canada in 2010, he took a job in a Tim Hortons convenience store. He is now a supervisor and is also attending a business college to study network administration. In spite of some militancy in Bhutan and in the camps, a response to the harsh conditions and harsh treatment, receiving countries have not experienced extremism from this wave of immigrants.

The diaspora respect their religious differences. It contains different strains of Hinduism, though many identify simply as Hindu. Caste distinctions were very much on the decline in Bhutan and are now declining even more in the receiving countries. And there are non-Hindus among the exiles. For example, Tkaram Garung is among a small number of Lhotsampa Buddhists. Some of the refugees have converted to Christianity in receiving countries. They all get along, an example for the rulers of the kingdom of Bhutan.

In spite of all, these ethnic Nepalis still identify as Bhutanese. In Canada their organization is called the Canadian Bhutanese Society, and Chabi has a Web site: www.bhutancanadanet.ca. While the Web site specifies Canada, it includes articles about Bhutanese Nepalis from around the world—except in Bhutan itself. There is little contact with Nepalis back in Bhutan. After phone calls and other contacts, word came back that people in Bhutan receiving them were harassed and even tortured.

Bhutan has lost hardworking, dedicated citizens. While some, especially among homesick elderly, would dearly love to return to Bhutan, those who have resettled abroad have found a new Gross National Happiness—elsewhere. Without torture!

Article Author: Reuel S. Amdur

Reuel Amdur writes from Val-des-Monts, Quebec, Canada.