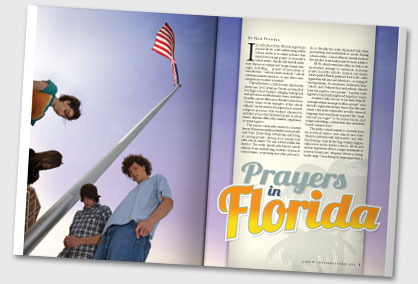

Prayers in Florida

Nan Futrell September/October 2012

In early March the Florida legislature passed SB 98, a bill authorizing public school districts to adopt policies that would encourage prayer at secondary school events. Specifically the bill authorizes the use of student-led "inspirational messages, including. . . prayers of invocation or benediction." School events include "school commencement exercises or any other noncompulsory student assembly."

The bill follows a 2008 lawsuit, filed by the American Civil Liberties Union on behalf of two high school students, alleging widespread and pervasive establishment clause violations by public school officials in Florida's Santa Rosa County. Some of the examples of the school officials' endorsement of religion and coercive religious practices that students objected to included actions that facilitated prayer at school events, whether offered by students, employees, or invited guests.

The parties ultimately entered a consent decree that permanently prohibited school officials from "promoting, advancing, endorsing, or causing prayers during or in conjunction with school events" for any school within the district. The order specifically barred school officials from authorizing students to pray at school events, or inviting any other person to do so. Finally, the order stipulated that, when permitting any individual to speak during school events, school officials should instruct the speaker to exclude prayer from its address.

SB 98, which went into effect in July, is an unabashed attempt to authorize sectarian prayer in public schools. Indeed, one media outlet quoted Florida governor Rick Scott—who signed the bill into law March 23—as saying of the legislation, "As you know, I believe in Jesus Christ, and I believe that individuals should have the right to say a prayer." Another state legislator reportedly expressed hope that "many . . . students [will] choose to use their time for an inspirational message to offer a prayer." And the bill's legislative history shows that the state senate education committee actually removed language that would have required the "inspirational messages" to be nonsectarian and nonproselytizing—a limitation the committee found "unnecessary."

The public school context is a favorite locus for political battles over church and state. Despite relatively well-delineated—and well-functioning—rules protecting student religious expression in the public schools, SB 98 and similar legislation reflect a larger movement to portray Americans' religious liberty as being under siege. Considering it's been more than a decade since the U.S. Supreme Court last addressed the topic of prayer in the public schools, it seems a topic worth revisiting.

The School Prayer Cases

The Supreme Court first considered an establishment clause challenge to a school prayer practice in Engel v. Vitale (1962),1 a case in which the High Court invalidated a school board policy that instructed all students to recite a state-composed prayer at the beginning of each school day. The following year the Court struck a state statute that required daily Bible reading in classrooms, even though students could be excused from the exercises by written request from a parent or guardian. In that case, Abington School District v. Schempp,2 the Court applied its emergent purpose-effect establishment clause test, writing that "if either [the purpose or the primary effect of an enactment] is the advancement or inhibition of religion then the enactment exceeds the scope of legislative power as circumscribed by the Constitution." This test—which would come to full fruition in the later case of Lemon v. Kurtzman—is one courts continue to employ today.

It is thus well established that school officials can neither compose prayers nor direct the content of any student religious messages. SB 98 was clearly written with these restrictions in mind, employing language that prohibits school personnel from participating in or influencing any student in (1) deciding whether to use a prayer as the inspirational message; (2) selecting the student volunteer who will give the inspirational message; or (3) determining the content of any such message. It also provides that the decision whether to use an inspirational message at a school gathering rests with the student government.

Often, though—and especially in matters of public school prayer—provisions that appear facially sound may guard against some establishment clause problems but invite others. Even internal analysis by a Florida senate education subcommittee acknowledged, "It is difficult to gauge how [SB 98] would be implemented in practice."

The High Court next confronted the issue of school prayer two decades later, in an establishment clause challenge to an Alabama statute that authorized a period of silence at the beginning of each school day for "meditation or voluntary prayer." The Court applied an enhanced secular legislative purpose test—again, reflecting developments in its own precedent—that asked whether the government's actual purpose in enacting a law was to endorse or disapprove of religion. The Alabama statute failed this prong: the Court concluded that the record unambiguously showed the law had no secular purpose. In particular, the legislative record quoted the bill's sponsor as explicitly stating that the law's sole purpose was an "effort to return voluntary prayer" to the state's schools.

Another aspect of the Alabama case, Wallace v. Jaffree,3 is especially germane to a discussion of SB 98. In Wallace an earlier version of the statute provided for a moment of silence, but mentioned only "meditation." The only notable difference between the challenged law and its predecessor was the insertion of the words "or voluntary prayer." This, the Court found, showed that the more recent statute had a purely religious nature.

The Court rejected Alabama's contention that the prayer statute was a valid attempt to accommodate students' free exercise rights, because in effect there had been nothing to accommodate: under the earlier statute, nothing had prevented students from using the legislatively authorized moment of silence for voluntary prayer.4 In essence the state could not show any secular purpose that was not entirely served by the prior law.

Likewise, Florida law already allows schools to designate up to two minutes each school day "for the purpose of silent prayer or meditation."5 Accordingly, SB 98 does not provide any necessary protection for students' (already secured) right to pray during the school day; and, compounding the problem, contemporaneous comments by state legislators suggest the bill was entirely motivated by lawmakers' intent to authorize more prayer. Taken together, these elements cast doubt on the law's stated purpose of "[providing] for the solemnization and memorialization of secondary school events," portending legal challenge.

The two most recent Supreme Court school prayer cases emphasized the special concerns that arise in the public school context. In Lee v. Weisman6 the Court invalidated a school's practice of inviting clergy to deliver sectarian prayers at school graduation ceremonies. It applied a "coercion test" that emphasized the "heightened concerns with protecting [students'] freedom of conscience from subtle coercive pressure in the elementary and secondary public schools." Students, the Court noted, are likely to feel pressure—even if "subtle and indirect"—to participate in a prayer when school officials supervise and control a school event. This places students in the constitutionally unacceptable position of either participating or protesting—the latter of which adolescents are less likely to do at school, where social conformity is highly valued. Further, it is irrelevant that a school event may be technically non-compulsory—schools cannot exact religious compulsion as the price of student participation in important school events.7

In Santa Fe Independent School District v. Doe,8 a Texas school district policy permitted student-initiated, student-led prayer at home football games. Pursuant to that policy, one high school conducted student elections to determine whether a prayer would be delivered, and if so, to select the student speaker. The Court struck the policy, finding the student prayer practice bore the State's imprimatur because of the degree of school involvement and placed objecting students in an untenable position. The fact that the policy's literal language referred only to "messages," "statements," and "invocations"—but not prayer specifically—was inconsequential. Moreover, the fact that the student speaker was selected through a student election process did not dispense with the harm: "The student elections take place because the District. . . 'has chosen to permit' student-delivered invocations."

As in Wallace, the school's decision to permit only one type of message—an "invocation"—was not necessary to protect students' right of free expression or to promote some other valid secular purpose. And as in Lee, it was irrelevant that extracurricular sporting events might be "voluntary" for some students.

The lessons of Lee and Santa Fe are manifold, but the essential takeaway is this: public schools warrant a unique establishment clause analysis. School officials have special duties to maintain neutrality in matters of religion; to avoid appearances of endorsement; and to distance themselves from truly voluntary private student expression. Students are impressionable and vulnerable to suggestions—even implicit ones—that school employees favor certain religious messages and disfavor others. Such legislation as SB 98 flouts these important constitutional commands.

At the same time, SB 98 belies the many ways in which student religious expression is already protected and permitted in the public schools. Students are free to pray and share their religious beliefs with others during noninstructional school hours. Voluntary, student-initiated prayer is welcome, as long as it isn't disruptive to others or the educational process. Students may gather for group prayer or Bible study to the same extent other student clubs do. Moments of silence are an appropriate means of permitting private student meditation, including prayer. And federal guidelines provide that "where student speakers are selected on the basis of genuinely neutral, evenhanded criteria and retain primary control over the content of their expression, that expression is not attributable to the school and therefore may not be restricted because of its religious (or anti-religious) content."9 The goal is to strike the appropriate balance between honoring individual private expression, which is constitutionally protected, and avoiding government promotion of religion, which is constitutionally forbidden.

It is important to recognize that the establishment and free exercise clauses are the "twin pillars" of religious freedom. In a 1998 "Letter to Educators," U.S. Department of Education secretary Richard Riley wrote, "The United States remains the most successful experiment in religious freedom that the world has ever known because the First Amendment uniquely balances freedom of private religious belief and expression with freedom from state-imposed religious expression." SB 98 suffers from too many of the constitutional flaws the Supreme Court has identified in its school prayer jurisprudence: it singles out "prayers of invocation or benediction" as a preferred type of message; it authorizes schools to facilitate student prayers at all school events; it disregards the implicit influence that school officials and peers project upon student speakers; and it is a wholly unnecessary means of protecting the free expression rights that students already enjoy. In short, SB 98 is little more than a solution in search of a problem.

1 370 U.S. 421 (1962).

2 374 U.S. 203 (1963).

3 472 U.S. 38 (1985).

4 The Court elaborated: "[The State's] arguments seem to be based on the theory that the free exercise of religion of some of the State's citizens was burdened before the statute was enacted. . . . [But in] this case, it is undisputed that at the time of the enactment of [the prayer statute] there was no governmental practice impeding students from silently praying for one minute at the beginning of each school day; thus, there was no need to 'accommodate' or to exempt individuals from any general governmental requirement because of the dictates of our cases interpreting the Free Exercise Clause" (id. at 57, n. 45).

5 See Fla. Stat. § 1003.45(2) (2011).

6 505 U.S. 577 (1992).

7 Id. at 595. ("Law reaches past formalism. And to say a teenage student has a real choice not to attend her high school graduation is formalistic in the extreme.")

8 530 U.S. 290 (2000).

9 SB 98 does not set forth "genuinely neutral . . . criteria" because it authorizes only "inspirational" messages—not student speech generally—and further singles out "prayers of invocation or benediction" as a preferred type of inspirational message. As the Supreme Court wrote in Lee v. Weisman, "a school official . . . decided that an invocation and a benediction should be given; this is a choice attributable to the State, and from a constitutional perspective, it is as if a state statute decreed that the prayers must occur" 505 U.S. at 587 (1992). Even though, under SB 98, the initial decision whether to offer an inspirational message may rest with a student volunteer, the statute essentially equates "inspirational" with "prayer," evincing a legislative decision that a religious message (if any) should be given.