Protecting Faith in the Workplace

James D. Standish July/August 2008

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Congressional testimony

by James D. Standish

—February 12, 2008

Chair Andrews, ranking member Mr. Kline, other members of the committee. It's an honor to represent the headquarters of the Seventh-day Adventist Church. There are about 15 million Seventh-day Adventists around the world. We operate over 600 health-care facilities and we have about 1.3 million students enrolled in our education system. I'm particularly proud of the work that we do for the least advantaged in our world. For example, our hospitals and clinics in Sub-Saharan Africa treat over 800,000 HIV/AIDS-positive patients every year. That is the outworking of our faith in our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ.

Another commitment that we make as Seventh-day Adventist Christians is to aim to keep the 10 Commandments, under the grace of Christ. That's all ten, including the commandment to rest on the Sabbath day. Increasingly, however, we're finding American employers unwilling to accommodate our sincerely held religious beliefs; and not just ours, but for people of faith across the religious spectrum. We've heard today from a Muslim woman, a Jewish representative. I'm a Christian. If you talk to Sikhs and other Christians you will find that this problem pervades across the spectrum.

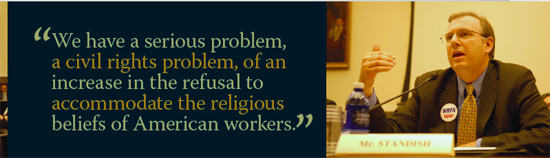

Indeed you don't have to just take our word for it; the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission reports that between 1993 and 2006, the number of religious discrimination claims filed with them went up 83 percent. That is a huge increase. During that same period, for point of reference, claims involving racial discrimination went down 8 percent, and other major claim categories also held steady or went down. We have a serious problem, a civil rights problem, of an increase in the refusal to accommodate the religious beliefs of American workers.

Part of the reason for this is the current weak state of the law, which permits employers to arbitrarily refuse to accommodate the sincerely held religious beliefs of employees. The Workplace Religious Freedom Act will fix the loopholes in the current law to ensure that when an American employee comes forth with a faith commitment that they're treated with respect and dignity, and if they can be accommodated, they will be accommodated instead of being marginalized in the American economy.

There are two principal objections to this bill.

First, we are told by opponents of the bill that this will result in an increase in litigation on employers. We know that's not the fact for two reasons.

- First of all, the economics of bringing these cases disfavors their bringing. Particularly, he amount of damage tends to be very, very low because the employees who are impacted disproportionately are low income employees. So the amount of damages, which [in these cases] is lost wages, is very, very small. Members of the private plaintiffs bar don't take these cases now; they're not going to take them after WRFA is enacted because the economics do not change.

- Second, we have an example up and going right now and that's in New York State where we have a WRFA-like standard. In New York State, we're being told by the [NY] Human Rights Commission there that the claims of religious discrimination have actually dropped four of the last five years. They dropped on the state basis; they will drop on the national basis, because it helps people come together.

Second, we are told that if WRFA is passed, it will result in perverse outcomes where third parties are harmed, whether those are gay, lesbian, bisexual employees being harassed in the workplace or an inhibition of patients to gain health-care services. Once again, we know that this claim is incorrect. We know that for two reasons:

First of all, the modest standard in WRFA would by no means require employers to refuse products or services on a timely basis. The standard just simply is not that strong.

Second, once again in New York we have this standard up and going, and opponents of this bill have yet to find a single case in which harassment was privileged in New York under the WRFA standard or services were denied. They have found claims that were brought nationwide over the last 30 years, a very, very small handful. In each case, the plaintiff lost. They lost then, and they will lose in the future [after WRFA is passed].

Before I close, I want to show you a picture. I can't help it; I'm a proud dad. These are my daughters. If my daughters grow up and they want to follow the faith of their mother, their two grandmothers, or their four great-grandmothers, how are they going to be treated in the workplace? Are they going to be marginalized? Are they going to be harassed? Are they going to be fired when they could easily be accommodated? I suggest to you this afternoon, the answer to that question is largely in your hands.

If we don't pass WRFA, the problem for Seventh-day Adventists and other people of faith in the workplace will increase. If we do pass it, we will have a balanced, bipartisan piece of legislation that finds the middle ground to ensure that the value of religious freedom and worker's rights are protected."

House Subcommittee on Health, Employment, Labor, and Pensions. Attorney Standish is legislative liaison for the world headquarters of the Seventh-day Adventist Church. He is also co-chair of the multifaith coalition which is working for passage of House Resolution 1431, or the Workplace Religious Freedom Act. Liberty has run a few articles on this proposal as it has gathered support. The bill is needed, as religious minorities in the workplace are increasingly being denied accommodation for their faith. While Title 7 of the Civil Rights Act prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, sex, national origin, or religion, courts are more and more allowing employers to provide only a "de minimus" accommodation. This was the second hearing within a year and there is hope that the already bipartisan support for the bill will increase and that religious faith in the workplace will be respected as the Constitution presumes. Editor.