Reformation Achieved

David J. B. Trim July/August 2009

This article is Part Four in a four part series. Click here for Part One, here for Part Two, and here for Part Three.

Religious diversity and thus the very concept of religious freedom in the modern United States both derive from the English Reformation, thanks to the English colonization of North America.

However, the Reformation in England is increasingly portrayed as something that was imposed on the English people by their rulers, who themselves did not have genuinely religious reasons for abandoning the traditional Roman Catholic faith of their forefathers. Some seem to feel that if it can be shown that the English Reformation’s root causes lay in political maneuvering, economic advantage, or personal foibles, and only succeeded because it was imposed by force on an unwilling or indifferent population, then its consequences could more easily be undone. What would hold back reunification of Protestants and Catholics, at least in the English-speaking world, if they are merely prisoners of an unfortunate history? And if the English Reformation were imposed by force, does it mark a black period in the history of religious liberty?

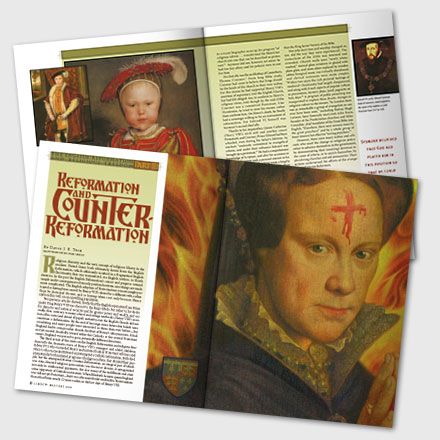

Three previous articles in this series have taken us from the origins of Henry VIII’s break with Rome in the late 1520s up to the death of Mary I in November 1558. This article looks at her successor, the third of Henry VIII’s children, Elizabeth I. By the time she took the throne there was more interest in, and sympathy for, Protestant ideas than on Henry’s death a dozen years before; however, England was not yet a Protestant nation. In the 30 years prior to Elizabeth’s accession, England’s official religion had changed radically, not once, but thrice; the “Elizabethan settlement of religion” (as it was to become known) was to be the fourth significant shift in 30 years—and the third in just over a decade! But it was also to be the last.

The reign of Elizabeth was to be a golden age for English literature, drama, culture, and exploration. On the stage, characters in the plays of Shakespeare, Marlowe, and Jonson grappled with issues that arose out of the wider contest between confessions for Englishmen and— women’s loyalty—issues that were both personal and national. The Elizabethan era was to be the metaphorical stage on which the drama of national religious choice was to be played out—and resolved. For in the next four decades, the ecclesiastical direction of the nation was to be decided for the next four centuries.

THE ELIZABETHAN SETTLEMENT

Immediately on succeeding her sister, Elizabeth replaced almost all the Catholic royal counselors and ministers of state with men who were known to be committed evangelicals. In the next four years, the newly Protestantized central government ensured that, in elections to Elizabeth’s first Parliament, the House of Commons (at that time elected by fewer than 1 in 10 of the population, who could often be swayed by the influence of government ministers) returned a majority of Protestant or at least antipapal MPs, albeit the House of Lords was more conservative. The queen’s counselors then shepherded through Parliament and through the Convocation (an assembly of the Church of England’s clergyman with limited legislative powers on ecclesiastical matters) the legal framework of “the Elizabethan Settlement.

”In 1559 Parliament enacted two key pieces of legislation: the Act of Supremacy and the Act of Uniformity, which restored both royal (rather than papal) authority over the church and the Protestant liturgy (the Book of Common Prayer) introduced in Edward’s reign. In 1563 Convocation adopted the Thirty-Nine Articles, which defined the faith of, and would regulate, the new Protestant Church, and also a new book of official homilies, which, used in conjunction with the Book of Common Prayer, were to be read aloud in every church during divine services.

However, the “Elizabethan settlement” was not a straightforward process. The queen and her ministers initially sought to put the clock back to Edward’s reign, but their first pieces of legislation, having passed the Commons, were rejected by the House of Lords—the upper house in Parliament. Opposition was led by the bishops, who of course were mostly staunch Catholics, appointed by Mary, and who wereex officio members of the House of Lords; but a number of the hereditary noblemen who made up the rest of the Lords were also ecclesiastically conservative. The government “had to make major concessions” to get the Lords to pass the two amended bills (passed once more by the Commons).1 The Act of Uniformity, which reimposed the Book of Common Prayer, was significantly altered, to make the liturgy at some key points ambiguous and hence acceptable both to Protestants and Catholics. Even then, the bishops still steadfastly opposed the bills. In a dramatic move, the government imprisoned two of the bishops and forcibly excluded two others from sitting, all on trumped-up charges. The legislation passed by 21 votes to 18—had the four bishops been present, the government’s program would have failed.

The Princess Elizabeth, aged about 13 (1546)

The initial Elizabethan program of radical reform thus was tempered by political necessity. Convocation proved easier to deal with than Parliament, but the Thirty-Nine Articles perforce reflected the revisions to the 1559 legislative program.

The young queen and some (though by no means all) of her ministers took the moral of the story to heart. After the upheavals of the previous decade, it is unsurprising that few people in the early 1560s realized the program eventually enacted during 1559–63 would “constitute a permanent ‘settlement’.”2 That it did was due not only to its nature, but also to the lessons learned and applied thereafter.

As we have seen, ambiguity was not originally the intent of the new regime. But Elizabeth had learned one lesson from the tumultuous reigns of her younger brother and elder sister—that pushing religious reform too far, too fast, only excited hostility that could politically undermine the sovereign. And the lesson she “learned from the clash of 1559” was caution.3 Thus, what she initially accepted perforce eventually became her preference. In contrast to the radicalism of the Edwardian reformation, which alienated as many as it appealed to, prudence and conciliation were to be hallmarks of the Elizabethan church.

What must, however, be emphasized is that, while Elizabeth’s ecclesiastical agenda after 1560 was, by the standards of the time, conciliatory, and was to be characterized by later generations as a via media (or middle way), it was not halfhearted. Some revisionist historians sneer at Elizabeth as “a Protestant (of sorts),” but it is widely recognized that the evidence we have for the queen’s opinions on doctrine (whether in public proclamations, from her own private devotions, or in her correspondence) reveals her theology as unequivocally Protestant.4 However, she emphatically was not a Calvinist—and it was the Calvinist, or Swiss, confession that commanded the allegiance of most leading English Protestant clergymen, and yet it was the most radical and divisive of the Protestant confessions. Elizabeth wanted her church, as much as possible, to unite her people rather than divide them—wanted it, in the language of the time, to “comprehend” as much of the population as possible.

The queen and some of her counselors seem to have decided that the moderation enforced on them by the opposition in the Lords in 1559 was a blessing in disguise, though it was not a view that all shared. Most of the new Protestant bishops, and some prominent Protestant nobles, were puzzled by the queen’s acceptance of what (to them) seemed a half-baked Protestantism. The celebrated theologian John Jewel, soon to be appointed bishop of Salisbury, wrote unhappily that some of his colleagues were “seeking

after . . . a mediocrity; and are crying out that the half is better than the whole.”5

Elizabeth and others of her ministers took a different view and apparently reached it quickly. The lord chancellor, Sir Nicholas Bacon, declared to the concluding session of the 1559 Parliament (in words that would have been approved by the queen): “I mean to comprehend as well those that be too swift as those that be too slow, those that go before the law or beyond the law as those that will not follow.”6 The set of injunctions which were issued that year by the government “for the suppression of superstition” and the promotion of “true religion,” and which provided for enforcement of the parliamentary legislation, “took more account of Catholic sensibilities” than the equivalents issued during Edward VI’s reign had done. They allowed for the preservation of much of the material culture of traditional churches, condemning the “superstitious abuse” of stained glass windows, crosses, altars, and so forth, rather than requiring their destruction (as particularly radical adherents of Calvinist Protestantism had hoped).7

THE ELIZABETHAN CHURCH OF ENGLAND

Elizabeth’s church, as it emerged from the Parliament of 1559 and Convocation of 1563, “blended traditional episcopal structure, an anglicised semi-Catholic liturgy, and a thoroughly Protestant theology,” as her brother’s had done.8 But Archbishop Cranmer and the other leading reformers of Edward’s day had seen the Edwardian church of the early 1550s as a staging post, a halfway house, to a more thoroughly reformed church in the future. In contrast, Elizabeth for the rest of her reign defended the church that, by accident as well as by design, had emerged in its first four years; it certainly was not Catholic, yet nor was it as unambiguously Protestant as many prominent Englishmen, clergy and laity alike, desired.

Under Elizabeth, the set liturgy of the Book of Common Prayer was identifiably Protestant; furthermore, many of the traditional rituals, around which communal worship and personal spirituality had centered, were abolished or altered significantly. This ensured the opposition of some traditionalists. Many other rituals, however, including some banned under Edward, were restored, or retained in somewhat modified form; and the same was true of much of the material culture of traditional worship: clerical vestments, the implements used in Communion, and the furnishings of the parish church.

All this angered the “hotter sort of Protestants” (as they called themselves), who, because of their passionate commitment to “purify” the Church of England of any residue of the Church of Rome, were to become known (by their enemies, more than by themselves) as “Puritans.” However, preserving traditional outward forms and the rites associated with them, even while preaching a distinctly new theology, provided much-needed continuity. It must have been reassuring to the many people who, while hostile to Rome, were bewildered by the multiple changes of confessional direction, had not heard much distinctly Protestant preaching, and were still uncommitted. It facilitated their conversion to what a subsequent generation of English Protestants would call “prayer book Protestantism.”

RELIGIOUS DIVERSITY

The compromises of the Elizabethan settlement thus did not negate all opposition —far from it. However, they did minimize opposition.

Many English people initially were unhappy with the Elizabethan settlement—yet crucially, very few hated it sufficiently to reject it entirely. There was enough in it that was familiar or desirable for it to be accepted—or at any rate not repudiated!—by a whole range of different opinion groups.

There were outright Roman Catholics (a small minority), and Henry VIII-style Anglo-Catholics, who hated the Papacy but disliked the doctrines and liturgical practices of Protestantism. There were middle-of-the-road evangelicals, essentially supporters of reform but still hoping for reconciliation in Christendom; and Lollards, the native English “heretical” movement, founded by John Wycliffe, almost 200 years earlier (whose absorption into Protestantism in the mid-sixteenth century remains one of the great mysteries of English reformation history). There were also, of course, out-and-out adherents of the reformed confessions: Lutherans; Calvinists; a few Anabaptists; but also followers of other Protestant reformers: Zwingli, Bucer, and Oecolampadius, whose followers in Europe had merged into the Lutheran and Calvinist confessions, but because of England’s separation from the continent, retained (for the moment) a quasi-separate identity.

Elizabeth I presiding over Parliment

This diversity among Protestants was well known. A common Roman Catholic charge was that they “cannot be the true Church, which is as a City at unity in its self, because of [their] manifold dissentions and divisions . . . the Doctrine of Luther was no sooner bred, and borne, but it divided it self like a Hydra into many heads: Lutherans, Calvinists, Anabaptists, Libertines . . . etc.”9 In a sermon preached at Oxford in 1555, a Catholic priest emphasized the newfangled “diversity in opinions” among English Protestants, who were “Lutherans, Oecolampadians, [and] Zwinglians,” in contrast to the “old . . . Catholic faith.”10

Members of these different Protestant groups disagreed, sometimes violently, over both the theology of the Eucharist (or Communion, or Lord’s Supper), and, in consequence, how it should be celebrated liturgically; they also differed, sometimes heatedly, over soteriology and ecclesiology (the doctrines of salvation and of the church). The revisions made in 1559–63 to the Act of Uniformity, Book of Common Prayer and Thirty-Nine Articles, and maintained and enforced over the next 40 years, were intended to conciliate not only Catholics but also different types of Protestants—for, without unity among them, there was no way to overcome the inertia of tradition which in circa 1560 still affected the majority of the population.

For much of Elizabeth’s reign there was doctrinally (though never ecclesiologically or liturgically) a “Calvinist consensus” at the top of the church. However, by the end of her reign the diverse strands in English Protestantism made themselves felt and a “new mood in English Protestantism” emerged—one that drew on a range of other Protestant traditions and embraced sacramentalist views more typical of Luther than of the Swiss reformers.11 It is a mistake, albeit one even distinguished historians are guilty of, to conflate English Protestantism with Puritanism; it was an error Elizabeth did not make.

“WINDOWS INTO MEN’S SOULS”

Why, then, did England become Protestant? The governments of Edward VI and Elizabeth I imposed what have been termed “political Reformations,” which certainly helped the process of Protestantization. However, in sixteenth-century France, the Netherlands, and parts of Germany, princes were unable to impose their religion on all of their subjects; early-modern society was far more hierarchical than ours, but early-modern people were just as willing as their ancestors and descendants to defy authority over a matter of conscience. The 36 years of the French Wars of Religion and the Eighty Years’ War in the Low Countries stand as potent testimony to the fact that sovereigns could not simply dictate their subjects’ religion. As one historian observes, the official Edwardian and Elizabethan reformations “could not make England Protestant” any more than the official Marian counter-reformation could make it Catholic. Nevertheless, “statute by statute,” Elizabeth gave England “Protestant laws and made popular Protestantism possible.”12

A page from the Book of Common Prayer

Furthermore, when English people had the chance to hear the gospel preached, on the whole, they responded enthusiastically. This took time, as recent revisionist histories make clear.13 One consequence of the Marian counter-reformation was that, in the early 1560s, there just were not enough committed Protestants in the clergy: in the circumstances, they simply could not “have made much progress.”14 Gradually, though, the divinity schools of Oxford and Cambridge started to turn out numbers of well-educated and zealous Protestant priests, who started to preach the gospel—and, even more, to celebrate the sacraments with the Book of Common Prayer. By the early seventeenth century, this wonderful liturgy (whose language, even more than the better-known King James Version of the Bible has decisively shaped the liturgical practices of all denominations throughout the English-speaking world) had won a devoted following, as recent research has shown.15 In the new grammar schools, too, children were educated as Protestants. Generational change ensured that, probably by the time of the attempted Catholic invasion of the Spanish Armada in 1588 (whose defeat was acclaimed in England as evidence of divine favor to a Protestant nation), the great majority of English people were Protestants. Whereas in the 1540s and 1550s the great question was whether England would be Roman Catholic or Protestant, by the 1640s and 1650s, it was what sort of Protestants English people would be—and it was one they felt so strongly about that it resulted in civil war and revolution.

Generational change could never have taken place, however, if, as in contemporary France, ordinary people were passionately devoted to maintaining Roman Catholic belief and practice. The English people accepted the new church—and probably did so not least because of the approach of its “supreme governor”: their queen.

Although it is often attributed to her, Elizabeth probably never actually said that she “did not wish to make windows into men’s souls.” But it may well have been said by her chief minister, William Cecil, and it certainly reflected Elizabeth’s attitude. As long as her subjects worshipped in her church each Sunday, using her liturgy, she did not mind what they thought. By modern standards, this is hopelessly intolerant! By the standards of the sixteenth century, it was remarkably open-minded. Elsewhere in Europe, both Protestants and Catholics sought to repress “heretical” opinion, as well as practice, and evidence of divergent thinking was punished with death. Elizabeth wanted unity among her subjects, and as long as they cooperated with her, she would not try to look into their minds and their hearts, to see if they did so enthusiastically or only grudgingly.

Inevitably, people of conscience from both ends of the confessional spectrum, Roman Catholics and Puritans, refused to acknowledge the queen’s right to govern their theology or how they worshipped—and refused, therefore, to participate in the services of her church. They were then persecuted, sometimes brutally, though on nothing like the scale of Mary’s persecutions. In response, some called for political resistance to the government, which in turn evoked even greater repression.

But this was not an issue for the great mass of Elizabeth’s subjects; thanks to the accidentally contrived but purposefully maintained via media of the Elizabethan settlement, most English people were not confronted with practices that flagrantly outraged their consciences. Their church was Protestant, but it did not advance only one restricted theological Protestant perspective, and so it appealed to a broad spectrum—at least it did not appall people sufficiently to defy the government. And so most people chose to conform outwardly and “took their places in church . . . [though] What they made of the service and the sermon we cannot say.”16 Many Puritans flocked to parishes of Puritan priests to hear their sermons; many Roman Catholics, as and when they could, sought out itinerant priests (missionaries from the Continent, who literally braved death) and took Mass. Yet many, from both ends of the confessional spectrum, still went to a prayer book service as well; this outward conformity was generally all that their queen wanted.

Thus, there was opposition from both ends, and there was some compulsion, but in the end it was not because of these that England became truly a Protestant nation, as well as having a Protestant church and state. It was because the majority of people, who, on Elizabeth’s accession were Catholic-leaning or uncommitted, were given mental time and space to adjust to the new national Protestant church. Then, over the space of a generation, the English people embraced it.

CONCLUSION

Looking back over the whole of the English Reformation, we can see that, while Henry VIII’s reign let the genie of religious diversity out of the bottle (though that was never his intention!), the reigns of his children were decisive in the transition of England from Catholic to Protestant. Yet although the personal religious preferences and policy choices of Edward VI, Mary I, and Elizabeth I were very influential, they did not, in and of themselves, determine England’s eventual confessional allegiance.

It was the choice of the English people to embrace Protestantism—it was not a free choice, because early-modern European governments did not allow their subjects the freedom to choose their religion; but it was still a genuine choice. Across Europe in the century after the Reformation, where populations and rulers were adherents of different confessions, widespread rebellions and civil wars broke out. That this did not happen in England highlights that a choice was made—and it was made for the Reformation. There were significant differences between Roman Catholicism and the different forms of Protestantism, and it was these, rather than the will of four Tudor sovereigns, much less the marital infidelities of Henry VIII, that shaped the process of religious change in sixteenth-century England and determined its outcome.

All Christians worship the same God and believe they are saved by the same Lord. Nevertheless, fundamental differences underlie the division between Catholic and Protestant and always have. Today, Protestants and Catholics coexist across the world, respecting each other’s sincerely held but distinctive doctrines, styles of worship, and approaches to spirituality. Respect is inconsistent with disdain; we should respect the choices of believers in the past, as well as in the present.

Accusing people of the past of insincerity in their decisions to become Protestant or to remain Roman Catholic is nothing new. It was commonplace in the sixteenth century. Protestants and Catholics accused each other of the same faults—of using religious rhetoric but actually only caring about wealth or power—blind to the irony that people on each side thought themselves sincere and the others hypocrites. The reality is that people in sixteenth-century England took the choices between Roman Catholicism and Protestantism and between different types of Protestantism very seriously: there were Catholic martyrs under Henry VIII and Elizabeth I, as well as Protestant martyrs under Henry VIII and Mary I. We should take their choices no less seriously; it is the best way to honor their commitment and to preserve the respect between different religions that is the best protection for religious freedom.

This article is Part Four in a four part series. Click here for Part One, here for Part Two, and here for Part Three.

- Christopher Haigh, English Reformations: Religion, Politics, and Society Under the Tudors (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993), pp.239-241, at 240. For details of how the Elizabethan settlement was eventually approved by the first Elizabethan Parliament, see Norman L. Jones, Faith by Statute: Parliament and the Settlement of Religion, 1559 (London: Royal Historical Society, 1982).

- Haigh, “The Church of England, the Catholics and the People,” in Haigh, ed., The Reign of Elizabeth I (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1985), p. 196.

- Haigh, English Reformations, p. 241.

- Ibid., p. 242.—but contrast p. 237: “Elizabeth herself was a Protestant, though an undogmatic one”; cf. Haigh, Elizabeth I (London: Longman, 1988), pp. 27, 28: “There can be little doubt of Elizabeth’s Protestantism.” See also, e.g., Jones, Faith by Statute, p. 9; Susan Doran, “Elizabeth I’s Religion: The Evidence of Her Letters,” Journal of Ecclesiastical History, p. 51 (2000): .699-720.

- Quoted in Jones, “Elizabeth’s First Year: The Conception and Birth of the Elizabethan Political World,” in Haigh, The Reign of Elizabeth I, p. 47.

- Quoted in Patrick Collinson, “Sir Nicholas Bacon and the Elizabethan Via Media,” Historical Journal 23 (1980): 255.

- Eamon Duffy, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England 1400–1580 (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1992), p. 568; Haigh, English Reformations, p. 242.

- David Cressy and Lori Anne Ferrell, eds., “Introduction,” Religion and Society in Early Modern England: A Sourcebook, 2nd ed. (New York: Routledge, 2005), p. 5.

- John Rolte, trans., A faithfull admonition of the Paltsgraves churches (London: 1614), sig. A3r (spelling modernized).

- In Cressy and Ferrell, Religion and Society, doc. No. 8, p. 38.

- Diarmaid MacCulloch, Tudor Church Militant (London: Penguin, 1999), pp. 204-209, at 208, 217-219.

- Haigh, English Reformations, p. 14.

- See esp. Duffy, and Haigh, English Reformations.

- Haigh, English Reformations, p. 250.

- E.g., Judith Maltby, Prayer Book and People in Elizabethan and Early Stuart England (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

- Collinson, “The Church and the New Religion,” in Haigh , The Reign of Elizabeth I, p. 173.