Reformation and Counter Reformation

David J. B. Trim May/June 2009

This article is Part Three in a four part series. Click here for Part One, here for Part Two, and here for Part Four.

Religious diversity and the very concept of religious liberty in the modern United States both ultimately derive from the English Reformation, which ultimately resulted in a fragmented English Christianity that was transmitted, via English settlers, to North America. In the past the English Reformation’s causes and progress seemed simple and its consequences obviously positive; however, now things are much more complicated. The English adoption of Protestantism is increasingly portrayed as having been caused by Henry VIII’s desire for a different wife, rather than by doctrinal dissent, and as having taken root only because Henry enforced his will on an unwilling population.

Two previous articles showed, firstly, that the English separation from Rome under King Henry VIII was due not to the king’s libido, but rather to his desire for dynastic and national security and for greater power and wealth; and secondly, that, contrary to many school and college textbooks, Henry VIII’s assertion of his own (and denial of papal) authority over the English Church did not constitute a Reformation. By the end of his reign more heterodox beliefs were circulating and more people were interested in them than ever before—but England had its own peculiar church, the fruit of Henry’s idiosyncrasies. It had not yet moved decidedly toward either the Catholic or the several Protestant camps. England was poised to go in potentially different directions.

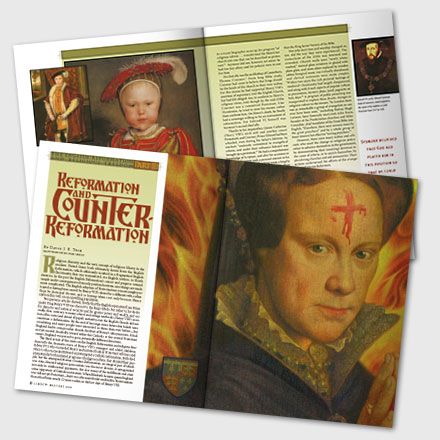

The third article of this series on the English Reformation and religious freedom tells the dramatic story of Henry VIII’s youngest and oldest children: Edward VI, who succeeded Henry and initiated radical Protestant reforms; and Mary I, who succeeded Edward and attempted a Catholic reformation. Both died prematurely; both initiated programs of religious reform that divided their people; but the attempted Marian Counter-Reformation, an integral part of which was state-directed religious persecution, was the most divisive. It antagonized not only its confessional opponents, but also many of the indifferent and even some supporters of Catholic restoration. When Elizabeth became queen England was still not yet Protestant—but it was a far more fertile seedbed for Protestantism than it had been nearly 12 years earlier, in the last days of Henry VIII.

PROTESTANTS IN POWER

Edward as Prince of Wales, c. 1546 shortly before his father King Henry Viii died.

Edward VI was only 9 years old when he succeeded his father as king in January 1547. The new king’s uncle, Edward Seymour, earl of Hertford, secured power as “lord protector,” but though he immediately promoted himself in the peerage to be duke of Somerset, Seymour was only partly motivated by desire for power; he also believed that God had placed him in this position so that he could lead England, its church and people, in a reformation.

Somerset probably had been leaning toward Protestantism for several years but, like a latter-day Mordecai, had carefully kept his views to himself during his tyrannical brother-in-law’s lifetime. On Henry’s death, Seymour was able to express himself, both personally and in policy. As a recent biographer sums up, his program “of religious reform . . . transformed the Henrician church into one that can be described as protestant.”1 Seymour did not, however, act alone: he had two key allies; and his policies were to outlive him.

His first ally was the archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer.2 From long Bible study, Cranmer had come to believe that kings should be the heads of the church in their own realms. For this reason he had supported Henry VIII’s assertion of supremacy over the English Church, but had felt obliged, too, to conform to Henry’s religious views, even though by the mid-1530s Cranmer was a committed Protestant. Like Nicodemus, he tried to steer his master, rather than confront him. On Henry’s death, he finally had a sovereign willing to be an instrument of reformation. For Edward VI himself was Seymour’s second chief ally.

Thanks to his stepmother, Queen Catherine (Henry VIII’s sixth wife and another covert Protestant), and Cranmer, Prince Edward had been schooled, even during his father’s lifetime, by teachers “zealously committed to evangelical reform, and under their influence Edward was brought up a protestant.”3 He had a comprehensive knowledge of Scripture, and after his accession to the crown Cranmer took a personal interest in his education. At age 11, the boy-king wrote a lengthy treatise on the papacy, concluding that “the Pope ‘is the true son of the devil, a bad man, an Antichrist and abominable tyrant.’”4 He even criticized his father’s religious policies, albeit blaming the pope for them. So indignant was the youthful Edward that he actually wrote of the pope, “He burns us ”—and had to be obliged by his tutors to write more dispassionately.5

RADICAL REFORMATION

Cranmer sought nothing less than to re-create the English Church. With the support of Seymour and Edward, he began to do just that.

Prince Edward in 1539, by Hans Holbein the younger. the following text is inscribed across the bottom: little one, emulate thy father and be the heir of his virtue; the world contains nothing greater. Heaven and earth could scarcely produce a son whose glory would surpass that of such a father. do thou but equal the deeds of thy parent and men can ask no more. shouldst thou surpass him, thou has outstript all, nor shall any surpass thee in ages to come. Sir Richard Morison

The language of the Eucharist and prayers was changed: for the first time, church services were in English. The Scriptures were read in English, too, and the so-called “Great Bible” (1540), translated during Henry’s reign at Cranmer’s urging, became integral to worship services, for which a new standard liturgy was introduced: the Book of Common Prayer. It promoted a distinctively Protestant theology, ecclesiology, and spirituality and probably has influenced the English language and culture more than the King James Version of the Bible.

Not only doctrines and worship changed; so, too, did the way they were experienced. The iconoclasm of the 1530s was renewed and extended. Church walls were “newly whitewashed,” stained glass windows re-glazed with plain glass, and stone altars replaced by wooden tables; liturgical music was virtually abandoned; and clerical vestments were made simpler. “Within two years the rich pictorial heritage of medieval Christianity had largely disappeared, and along with it such aspects of popular culture as processions, mystery plays, [and] pageants on holy days.”6 A program of public preaching was inaugurated to explain these drastic changes in religious culture to the masses. “In London there was as remarkable a group of evangelists as can ever have been seen,” including Bishop Hugh Latimer, later famously martyred; John Knox, founder of the Presbyterian churches; and Miles Coverdale, chief translator of the Great Bible into English. “Elsewhere, there were sermon-tours by the great preachers” and by a whole group of lesser-known but effective “roving preachers.” 7

However, there were many nobles and officials who used the change in religious policy either to advance themselves in the government, by demonstrating their (seeming) devotion to the cause of reform, or to enrich themselves, by plundering churches and old monasteries. Their actions undermined the efforts of the evangelists and sincere Reformers.

RESPONSES TO REFORMATION

The execution of John Rogers at Smithfield, London in 1555. Cranmer’s alliance with Edward was so close that it outlasted Seymour. In 1547 the regency faced widespread peasant rebellions. In the east of England the concerns of the lower orders were largely socio¬economic in nature, but their demands were partly expressed in Protestant language, and the rebellious peasantry listened to Protestant sermons. In contrast, the West Country rebellion seems to have been triggered by the introduction of the first edition of the new prayer book, copies of which were burned en masse by the peasants, who demanded the restoration of the church as it had been in Henry’s day. Hastily imposed, wholesale, and radical, the government’s innovations in religion were dividing the nation, satisfying some ordinary people, but deeply alienating many others.

Seymour took the blame, and in October 1549, after the rebellions had been quelled, he was overthrown by an aristocratic coup. Yet the regime’s religious policies did not change. To strengthen his grip on power, the new regent, John Dudley, duke of Northumberland, cleverly accommodated the adolescent king’s “keen intelligence and . . . sovereign will.”8 And that meant endorsing further reformation, for Edward was a zealot. In 1550, for example, about to witness the “official confirmation of the aggressively advanced reformer John Hooper as bishop of Gloucester,” the king noticed that Hooper was about to be asked to take an oath whose wording was traditional and Catholic; Edward promptly “struck out” the offending words “with his own pen.”9

Due to Dudley’s policy of indulging Edward’s enthusiasms, the intelligent, well-educated, and willful young king, mentored by Cranmer, increasingly shaped the regime’s religious policies. Many of the reforms described earlier were implemented fully after 1550, and a second, even more radical edition of the Book of Common Prayer was issued in 1552. Leading Reformers recognized that “official Protestantism was still a minority faith,” but it must have seemed to contemporaries that by the time the vigorous young king had grown old and died, England would be unambiguously Protestant.10

And then, in the spring of 1552 Edward contracted tuberculosis. A year later his illness took a fatal turn and he died on July 6, 1553. Desperate to preserve “his proceedings in religion,”11 he tried to ensure that the crown passed not to his Catholic eldest sister, Mary, nor even to his evangelical elder sister Elizabeth, but to his radically Protestant cousin, Lady Jane Grey.

Edward VI’s almost bizarre attempt to flout English law speaks eloquently both of the strength of his attachment to reformed religion, yet also of the shallowness of its roots on his death, that such extraordinary measures were necessary to preserve it.

CONSERVATIVE REACTION

For all Edward’s wishes, Jane “ruled” England for only nine days before Mary swept into power. In that brief interregnum Mary carefully worded her public pronouncements so as to leave her future religious policy vague; many devout Protestants supported her succession, for she unquestionably was legally the rightful heir to the throne.

Once she safely wore her father’s crown, however, Mary I set about to undo not only her brother’s radical reformation but even her father’s more moderate reform. When she summoned her first parliament, there was widespread surprise at “the scope of the legislation designed to turn the clock back to 1529.”12 Those who resisted would have to face the full weight of the ancient sanctions against heresy. Although today we know that she was to fail, we need to put ourselves in the circumstances of 1553. If many people had been won over by the reformed liturgical and theological regime, many were appalled by it. For many others, there seems to have been yet no clear sense of what was “Catholic” and what was “Protestant.” While there was widespread openness to new, heterodox doctrines and practices, at the same time, innate attachment to time-honored forms of worship (and, to a lesser extent, to traditional beliefs) was pervasive.

Hugh Latimer is depicted preaching to King Edward Vi in this woodcut from John foxe’s Acts and Monuments, better known as Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. by the time this book was published in 1563, edward Vi was revered as a pious patron of the english reformation, a new Josiah who loved nothing better than to hear sermons, during which he often took notes. He is portrayed here listening from a gallery to a sermon by bishop Hugh latimer, who, along with thomas Cranmer and nicholas ridley, was a key figure in the development of Protestantism in edward’s reign and, like them, a martyr under edward’s Catholic successor Queen Mary I.

Thus, had Mary acted differently, then England might well indeed have been led back to the Roman fold and become once more the bastion of the Catholic Church it had been only 30 years earlier. Instead, her conduct as sovereign helped to achieve the opposite of her intention.

Mary had been brought up a devout Catholic. Her father had slighted and discarded Mary’s mother and had even, in 1534, proclaimed Mary herself illegitimate—a cruel act; though by 1543 he had declared her legitimate again, restoring her to the succession, he also regularly made her life difficult because she refused to conform to his church. Mary unsurprisingly had a bitter, personal hatred of “heresy,” which she associated with the loss of her father’s love, the destruction of her family, and the disruption of her life. She had, moreover, yearned for nearly 20 years for the day when traditional religion could be restored to England. Her animus against Protestantism and enthusiasm for her faith led her into a series of disastrous decisions (not all of which need concern us here).

Mary recognized that all her subjects had been obliged to participate in heretical religious rites, and that some had actually embraced heresy, but she and her advisers thought that England had been hijacked by a small number of extremists, and that on their elimination the great mass of people would happily return to traditional religion. The new regime realized that decided, doctrinaire Protestants were a minority but failed to comprehend that so were convinced, committed Catholics.

Yet it might not have mattered if Mary had realized her mistake. Her personal history meant that there was no prospect that, once firmly on the throne, she would go slowly or softly. Those who had been forced to dabble with false religion and those who had done so willingly would all be given a chance to recant and return to the embrace of the true church. But those who, in contemporary parlance, “contumaciously” clung to their heresy would receive no mercy.

THE FIRES OF PERSECUTION

Thomas Cranmer’s execution in 1556. Perhaps nothing did more to doom Mary’s attempted Catholic restoration than her regime’s determined persecution of all dissidents. Mary I has been known to generations of English and American schoolchildren as “Bloody Mary.” Recent scholars point out that, to political (rather than religious) opponents, she was merciful rather than “the simplistic bloody tyrant of protestant mythology”;13 and they emphasize that her failure to reestablish Catholicism was by no means inevitable.

Nevertheless, one cannot simply ignore the Marian persecutions, which were on a scale unparalleled in English history, then or since. Mary’s ecclesiastical policy was central to her reign. To be sure, the queen was not simply vindictive. Along with Cardinal Pole and her other bishops, she “wanted converts, not martyrs” and “thought [that] heresy was a minority problem,” which “a few salutary burnings” would crush.14 However, evidence to the contrary soon piled up, as did the number of executions for heresy—but they did not stop, though the queen could have halted them at any time. Some of her councilors eventually advised a more merciful policy, including even Cardinal Reginald Pole, papal legate and Mary’s archbishop of Canterbury. Yet the executions continued. In the area of religion, the unwelcome sobriquet of “bloody” is deserved.

Burning at the stake had never been as common a punishment for heresy in England as it had elsewhere in Europe. The horrors of immolation were thus even more shocking for mid-sixteenth-century Englishmen and- women than for people on the continent.

Thomas Cranmer originally recanted—his faith shaken by the apparent overturning of what he had thought was God’s will, and by witnessing others burning alive—but later he publicly disavowed his retraction of Protestantism and was burned at the stake. Four other bishops were likewise executed: the radical John Hooper, burned outside his own cathedral at Gloucester; Robert Ferrar, bishop of Saint David’s in Wales; and Hugh Latimer, who famously bid Nicholas Ridley, who was burned with him, “Be of good comfort, Master Ridley, and play the man: we shall this day light such a candle by God’s grace in England, as (I trust) shall never be put out.”15 These executions of ecclesiastical hierarchs had a shocking quality for sixteenth-century people impossible to grasp in our democratic age. But the horror of five elderly men being burned alive is not just one we share today; it also features strongly in contemporary reports. While many victims died relatively quickly and painlessly from smoke inhalation, others (including Hooper and Ridley) literally burned slowly to death, suffering appalling agonies that traumatized onlookers.

thomas Cranmer’s execution in 1556.

If the stories are horrifying, so are the statistics. Mary’s government executed at least 287 people in 46 months from February 1555 to November 1558, when Mary died. Nor was there any letup in persecution—the last victim, Agnes Prest, was burned while Mary literally was on her deathbed. Although the high-profile executions of bishops drew much attention, the majority of martyrs were common, working people. They were often burned in batches of five or six—but, at least once, 13 were executed in one great conflagration. Fifty-one (more than one in six) were women, including a 60-year-old widow and a blind girl.16 While the majority of executions took place in London, the capital and largest city, Protestants were also burned in towns both small and large across England and Wales: Beccles, Cambridge, Canterbury, Cardiff, Carmarthen, Colchester, Dartford, Derby, Exeter, Gloucester, Newbury, Norwich, Oxford, Reading, St. Albans, Swansea, and others. A large part of the English population was exposed to the horrible spectacle of burning at the stake.

During 37 years of the reign of Henry VIII, some 50 heretics had been burned at the stake, while in its last 15 years, 69 Roman Catholics had been executed. Under Edward, there had been just two executions on religious grounds (an anti-Trinitarian and an Anabaptist). Elizabeth I, in a 44-year reign, was to execute six heretics and another 187 Catholics for religious reasons. Thus, Mary’s brutal father had executed on average not quite one and a half heretics a year in his reign, plus nearly five people per year after his break with Rome for denying the royal supremacy over the Church of England; under Elizabeth I all executions for religious reasons averaged about four a year. In sharp contrast, the average number of people executed during the Marian persecution was more than 70 per year. More people were killed during Mary’s reign, though it was the briefest of any sovereign in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, than under any other Tudor (or any Stuart, for that matter).

THE EFFECTS AND END OF PERSECUTION

Hugh Latimer is depicted preaching to King Edward VI in this woodcut from John Foxe’s Acts and Monuments, better known as Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. By the time this book was published in 1563, Edward VI was revered as a pious patron of the English Reformation, a new Josiah who loved nothing better than to hear sermons, during which he often took notes. He is portrayed here listening from a gallery to a sermon by Bishop Hugh Latimer, who, along with Thomas Cranmer and Nicholas Ridley, was a key figure in the development of Protestantism in Edward’s reign and, like them, a martyr under Edward’s Catholic successor Queen Mary I. The burnings were produced by the determination of ordinary Protestants to witness for the truth, and the determination of ordinary Catholics to destroy error.”17 But to many English people, this clash of ideologies discredited both those who did the burning and their system of belief. It was not merely that people were revolted by so appalling a form of execution on such an alarming scale, though they undoubtedly were; but they also drew conclusions about those responsible. Within three days of Cranmer’s execution in 1556, a foreign Catholic ambassador in England wrote of the “commotion” it had produced among common people, “as demonstrated daily by the way in which the preachers are treated, and by the contemptuous demonstrations made in the churches.”18 The same year, the bishop of London was told by one devout adherent of Rome that the heretics did more harm in their dying than in living. By 1558 burnings were so unpopular that many were staged “at dawn to ensure minimum publicity.”19

Nevertheless, there were some who viewed the burnings and felt that the executed heretic had it coming, while others responded only with mild distaste. Had Mary lived another 10-15 years and the program of persecution combined with Catholic evangelism been able to continue, then, given the embryonic nature of organized Protestantism in the 1550s, the Marian Counter-Reformation might have succeeded. England probably would have become like France, where Protestants were significant and influential, but very much a minority—in which case England, like France, might have suffered a series of violent civil wars of religion. However, England possibly might, like Italy, Spain, and Austria, have become almost completely Catholic. In either case, the implications for global, not just European, history would have been immense, because either the extraordinary wave of English colonization would not have occurred, or the English would have planted in North America and Australasia “the cobalt flag of the throne of Peter.”20 Had the United States ever even come into existence, it would have been dramatically different.

These possibilities remain, however, mere hypotheses or fantasies. For Mary contracted cancer and, on November 17, 1558, she died. She had married late, had no children, and so she was succeeded by the middle child of Henry VIII, Elizabeth, who was a committed, though not dogmatic, Protestant—and had been lucky to survive her sister’s reign. The fires of persecution were put out. England was about to undergo another radical change of religious direction.

CONCLUSION

What, then, was the state of English religion in 1558, on Mary’s death?

England had undergone an extraordinarily swift series of dramatic, diametrically opposed changes in religion, which must have been bewildering and destabilizing. Many ordinary English people were alienated by the massive changes, especially in the way they experienced religion, which amounted to a religious “cultural revolution,” as the most distinguished historian of Puritanism, Patrick Collinson, put it. “Many people voted with their feet against the new services” and absenteeism from church became a matter of great concern for Edward VI’s reforming bishops—and have been emphasized by some historians. However, similar problems were noted during Mary’s reign. Those who favored a traditional style of worship returned to church, but the people who now preferred a more radical, distinctively Protestant, style stayed away. Many, perhaps most, of those charged with heresy during Mary’s reign had been converted during Edward’s reign—conversions they described “with pride.” Not everyone felt able openly to defy the government, but clearly many people had been won over, at least in their sympathies, to a Protestant style of worship; they might not risk burning as a heretic by openly denouncing Catholic worship services, but they could resist passively—and they did. “The background to the fresh crop of Marian absentees [from church] was an Edwardian success story which had bred real hostility to Queen Mary’s reversal of religion.” 21

In fact, the Edwardian combination of favorable laws and widespread preaching had undoubtedly had a significant “impact . . . on ordinary people.” 22 As one agricultural laborer later recalled, “By the preaching of the Word” the seeds of Protestantism had “been sown most plentifully . . . in the days of good King Edward.” 23 Although out-and-out Protestants were still a minority, there were many more than there had been on the death of Henry VIII—and crucially, too, sympathy for Protestant ideas was much more widespread. The Marian persecutions had, moreover, served to create deep-seated hostility to the Church of Rome—denial of religious freedom had achieved the exact opposite of its intention.

Government by a zealous Protestant regime and then by an equally zealous Catholic regime had, in sum, served to advance Protestantism. But England had not yet been transformed into the Protestant nation of the history books. Elizabeth was a Protestant queen; the majority of her people had still to decide definitively where their confessional allegiances lay.

This article is Part Three in a four part series. Click here for Part One, here for Part Two, and here for Part Four.

- Barrett L. Beer, “Seymour, Edward, duke of Somerset (c. 1500–1552),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept. 2004; online ed., Jan. 2008 (www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/25159, accessed May 2, 2008).

- The authoritative biography is Diarmaid MacCulloch, Thomas Cranmer: A Life (New Haven, Conn. & London: Yale University Press, 1996).

- Dale Hoak, “Edward VI (1537–1553),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept. 2004; online ed., Jan. 2008 (www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/8522, accessed May 2, 2008).

- Diarmaid MacCulloch, Tudor Church Militant: Edward VI and the Protestant Reformation (London: Allen Lane/Penguin Press, 1999), p. 26.

- Ibid., pp. 29,30, 226, emphasis added.

- MacCulloch, Thomas Cranmer, p. 511; Hoak, “Edward VI.”

- Christopher Haigh, English Reformations: Religion, Politics, and Society Under the Tudors (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993), pp. 189, 202; Brett Usher, “Essex Evangelicals Under Edward VI: Richard Lord Rich, Richard Alvey and Their Circle,” in David Loades, ed., John Foxe at Home and Abroad (Burlington, Vt.: Ashgate, 2004), p. 52, and cf. p. 54.

- Hoak.

- MacCulloch, Tudor Church Militant, pp. 35, 36.

- Haigh, p. 202, and cf. p. 183.

- Quoted in Hoak.

- Ann Weikel, “Mary I (1516–1558),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept. 2004; online ed., Jan. 2008 (www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/18245, accessed May 16, 2008.

- Ibid.

- Haigh, pp. 224, 231.

- John Foxe, Actes and Monuments, 4th ed. (London: 1583), p. 1770 (spelling modernized).

- Haigh, p. 230; John Guy, Tudor England, pb. ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), p. 238.

- Haigh, p. 231.

- Quoted in MacCulloch, Thomas Cranmer, p. 607.

- Haigh, p. 234; Guy, Tudor England, p. 486.

- Geoffrey Parker, Spain and the Netherlands 1559-1659: Ten Studies (London: William Collins Sons, 1979), p. 144.

- MacCulloch, Tudor Church Militant, pp.106, 108; Patrick Collinson, The Birthpangs of Protestant England: Religious and Cultural Change in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1988); Haigh, p. 190.

- MacCulloch, Tudor Church Militant, p. 108.

- Quoted in Haigh, p. 198.