Religion in the Public Square

Céleste Perrino-Walker May/June 2003

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Illustrations by David Klein

In the Northeast, where I live, we have a saying: "If you don't like the weather, wait a minute." The same holds true in an interesting case involving the Main Street Plaza in Salt Lake City, Utah. Its legal briefs have more twists and turns than a Grisham thriller. The issues involved have slashed through the City of Salt Lake, dividing its fair citizens.

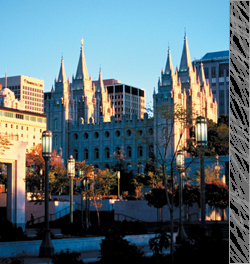

It all started when the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (the LDS Church) and the City of Salt Lake struck a deal in 1999. For the princely sum of 1 million dollars the LDS Church bought a 660-foot section of Main Street aptly nicknamed "Soapbox Corner" at the turn of the century, because of all the speechmaking that went on there (the significance of this has escaped no one). This section comprises a downtown block, which runs in front of the Mormon temple from North Temple to South Temple streets. Following the sale the LDS Church made major improvements to the block, transforming it into a plaza with fountains, flowers, reflecting pools, and statues. The city, meanwhile, spent the money.

Because this section of land is a major thoroughfare, the city retained easement rights to ensure pedestrian passage. The trouble is that the LDS Church imposed, and the city accepted as part of the deal, a list of restrictions on the conduct of people passing through their section of Main Street. The list of outlawed activities reads, in part: "loitering, assembling, partying, demonstrating, picketing, distributing literature, soliciting, begging, littering, consuming alcoholic beverages or using tobacco products, sunbathing, carrying firearms (except for police personnel), erecting signs or displays, using loudspeakers or other devices to project music, sound or spoken messages, engaging in any illegal, offensive, indecent, obscene, vulgar, lewd or disorderly speech, dress or conduct, or otherwise disturbing the peace."1 Anyone not conforming to the restrictions would be banned from the property.

The LDS Church itself has no such restrictions on its own behavior in the plaza. In fact, it is "without limitation," as the easement puts it. "The provisions of this section are intended to apply only to Grantor and other users of the easement and are not intended to limit or restrict Grantee's use of the Property as owner thereof, including, without limitation, the distribution of literature, the erection of signs and displays by Grantee, and the projection of music and spoken messages by Grantee."2

The LDS Church, being quite serious about the restrictions, began to enforce them. Several people were arrested or given citations. Kurt Van Gorden, director of Utah Gospel Mission, and Melvin Heath were two such "trespassers." "The Utah Gospel

Mission has been passing out gospel literature in Utah since 1898," Van Gorden said. "The very block of Main Street in question has been a place we have done mission work for the past 25 years. And we feel that right [to do mission work] was taken away through the sale of the property. It was impinged by the Mormon Church. They have the right to say who can be there. Their missionaries are allowed there, and ours aren't. We're saying that in the United States we need equal footing for all missionaries and all religions, not discriminating against one and in favor of another."

Van Gorden was arrested by Mormon security guards when he attempted to pass out tracts along the easement. "It was a public easement," he said. "We went down there and passed out our tracts and the Mormon security guards arrested us. The police only effected the arrest that was officially done by the security of the Mormon Church."

The first day Van Gorden was given a citation for trespassing, which was later dismissed by a judge during his arraignment, and willingly left with police officers called by the Mormon security guards. The second day he was handcuffed and taken to jail. Others received citations as well.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) filed a suit on behalf of the First Unitarian Church of Salt Lake City, and the Utah branch of the National Organization for Women and Utahns for Fairness, arguing that the restrictions violated First Amendment rights. U.S. district judge Ted Stewart ruled against the ACLU, finding that the easement, while allowing the public passage through the plaza, didn't preserve any rights of speech.

|

| Salt Lake Convention and Visitors Bureau. Jason Mathis |

The ACLU appealed Judge Stewart's decision to the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals. The outcome was a three-judge panel reversing the U.S. district court's decision and ruling that the sidewalks of the Main Street Plaza are a public forum. But the buck didn't stop there. The LDS Church filed an appeal to the full court, hoping to overturn the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeal's ruling. They cited the ruling as inconsistent with an earlier 1999 case in Denver in which the same court "found that a First Amendment public forum didn't exist on a secular pedestrian plaza created when the city closed a street that ran through the Denver Performing Arts Center campus."3 The situation varies somewhat, however, in that the Denver plaza is described as a covered, elevated terrace that is essentially an extended lobby for the Denver Performing Arts Center. One of the judges who sat on both cases did not see the rulings as inconsistent. The hearing was subsequently denied.

The LDS Church has intimated that it might appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court. And here everyone sits, waiting for an outcome that will satisfy someone. While the legal parties play tennis with this case in court, the daily result of the sale is the effect it has on the citizens of Salt Lake City and the LDS Church, which now, in effect, owns a public property where anything goes, right in front of its temple. And it paid a whopping price for the privilege too. As the property owners the LDS Church should be allowed to designate what does and doesn't happen on their land. Herein lies the crux of the matter. The LDS Church and the City of Salt Lake, both with, as far as anyone can tell, pure and honest intentions, agreed to the sale, including the easement and restrictions.

But they blinded themselves to what would happen if the restrictions, because of the location, i.e., Main Street, which is traditionally a public forum, were deemed unconstitutional. It seems clear that the LDS Church would not have purchased the land without the restrictions, and the city would not have sold it without an easement.

However, there is evidence that someone along the line had doubts about whether the restrictions would fly in the face of constitutional rights, because there is a severability clause stating that "in the event that it is finally determined by a court having jurisdiction over Grantee or the Property that any of the terms, conditions, limitations or restrictions set forth in this instrument are unconstitutional or otherwise unenforceable, the remaining terms, conditions, limitations and restrictions set forth herein shall remain binding and enforceable."4 Meaning that the LDS Church gambled on their restrictions not being unconstitutional.

This presents no small conundrum for all parties presently involved. The current mayor, Ross C. "Rocky" Anderson, inherited this dilemma and is trying to do right by all parties involved. He stated in an opinion editorial submitted to the Salt Lake Tribune and the Deseret News regarding the Main Street Plaza, "Some who have made demands have done so with righteous indignation that

I would abide by the written agreement that was negotiated at length and drafted with the help of several lawyers representing the Church of Jesus Christ and the city. Ironically, I am being criticized by officials of The Church of Jesus Christ and DeeDee Corridini 5 for refusing to significantly alter a contract negotiated, drafted, and signed by them."6

Mayor Anderson has written several statements regarding this issue and suggested possible alternatives that would give what he calls a "win-win" outcome to the stalemate of the plaza issue. One such alternative is beguiling in its intention. In it the mayor proposes a compromise solution. Essentially the city would extinguish the easement. In exchange the LDS Church would donate 2.17 acres it owns on the west side of Salt Lake City to be developed into facilities to provide "opportunities to west side residents, including such things as early childhood programs, after-school and summer youth programs, art programs for young people and adults, business mentoring, legal services, and adult education classes."7 In addition, the mayor proposes that expanded health-care services be provided.

Support for the plan was indicated by the pledges of people willing to help turn such humanitarian dreams into reality. "James Sorenson has pledged a million matching gift. The Jon M. Huntsman Family and the George S. and Delores Dore Eccles Foundation have agreed to jointly match that million gift."8

There's more to it. Altogether there are eight points, or terms, to Mayor Anderson's proposal. On the surface it seems to be an ideal trade, and the mayor seems sincere. And he's not letting any moss grow on his idea either. Josh Ewing, communications director for the mayor, confirmed that Mayor Anderson had already filed a petition to vacate the easement, which will start the public process for consideration of this proposal.

However, as tempting as it might be to trade something only non-Mormons truly want (the easement) for a noble humanitarian cause (helping the less-affluent west side of the city), what it really boils down to is trading freedom for goodness. If our freedoms are traded for anything, no matter how honorable or noble it is, how then can we truly be free? If we can trade freedom of speech for "remarkable humanitarian objectives,"9 what then will we trade our other freedoms for? What is freedom of religion worth? Soup kitchens? Homeless shelters? World peace?

Freedom can't be bought and it can't be sold and it can't be traded for even the very best of humanitarian causes. Freedom is priceless. We would do well to remember that in times like these.

The battle lines have been drawn around free speech rights, but in a town like Salt Lake, where you're Mormon or you're not, it's rarely "just" about free speech. "The ACLU also claims that the city's sale of Main Street to the church is an establishment of religion by 'giving the indelible impression that the LDS Church occupies a privileged position in the community.' The debate isn't new, says John McCormick, a history professor at Salt Lake Community College. Ever since the turn of the century, when non-Mormons became half the city's population, the church has tried to reassert its authority.

"Salt Lake City is what may be called a contested site," McCormick said. "Who's Salt Lake going to belong to? Who will have a voice and who won't, and what position will groups occupy in the city? The sale of Main Street fits right into that."10

And take into account that the original sale of the land by the city council was passed by a vote of five to two—five Mormons in favor and two non-Mormons against.11 All this has created an "us against them" feeling in the city. "More than half—58 percent—of Wasatch Front residents say the plaza issue has affected relations between Mormons and non-Mormons, according to a poll conducted last week for the Salt Lake Tribune."12

And then there is the question about the rights of the disabled, should the easement be vacated. The Americans with Disabilities Act comes into play here too, maintains Van Gorden, who is concerned about what would happen to the disabled should the easement be dissolved. In a letter to Mayor Anderson he says, "Giving the public easement away harms the non-LDS disabled people, whom you have a duty to protect. Those on canes, walkers, crutches, or using wheelchairs, must be guaranteed that they will not have to struggle to remove a shirt, jacket, hat or cover a bumper sticker or other slogan prior to crossing between North and South Temple streets on the public easement of the Main Street Plaza, simply because such may be considered an inappropriate message by LDS monitors. Otherwise, non-LDS disabled people will be forced to struggle along three additional blocks to get to the same point that is one block over the easement today if they believe in a specific cause and wear it on their clothing or wheelchair."13

Free speech may be the most prominent issue in this case, but it's certainly not the only one. For the time being, the LDS Church owns 660 feet of controversy in a city that is rapidly choosing up sides along religious lines. It would take a judge as wise as Solomon to settle so sticky a dispute. Too bad he's not available. Unless an eleventh-hour compromise is reached, the Supreme Court could be the ones to write the end of this legal thriller.

____________

Celeste perrino Walker is a much published author of books and articles, with a long-standing interese in legal "conundrums." She writes from Rutland, Vermont

_____________

1 Main Street Easement, Special Warranty Deed, executed Apr. 27, 1999.

2 Ibid.

3 "Mormon Church Appeals Main Street Free-Speech Ruling," The Associated Press, Oct. 24, 2002.

4 Main Street Easement, Special Warranty Deed, executed Apr. 27, 1999.

5 DeeDee Corridini was the mayor at the time of the Main Street sale.

6 "Mayor Anderson Calls for Keeping Promises on Main Street Plaza," Ross C. "Rocky" Anderson, submitted Nov. 26, 2002, www.slcgov.com/mayor/speeches/plaza%20oped.htm.

7 "Statement of Mayor Ross C 'Rocky' Anderson Regarding Main Street Plaza Resolution Proposal," Dec. 16, 2002, www.slcgov.com/mayor/speeches/plaza%20resolution%20speech.htm.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 "ACLU Sues Salt Lake City Over Deal With Mormon Church," Associated Press, Nov. 17, 1999.

11 "Mormons Purchase Portion of Utah Public Street, Create Code of Conduct," Associated Press, May 7, 1999.

12 "SLC Council Hears Main Street Plaza Issue," Associated Press, Dec. 18, 2002.

13 Kurt Van Gorden, director, Utah Gospel Mission, to Mayor Ross C. Anderson, Nov. 7, 2002.