Religious Wars and Religious Freedom: A Troubled History

David J. B. Trim March/April 2010

Although today Western society generally accepts that freedom of religious belief and expression is an innate human right, that position emerged only after centuries of religious intolerance and persecution, and centuries of interreligious hatred so extreme that it frequently resulted in wars of religion. This article is the first in a four-part series exploring the history of religious and holy war in late-medieval and early-modern Christendom.1 Religious wars have been fought in other areas, of course, and in other epochs; however, from the late fourteenth to the early eighteenth centuries Europe was the stage on which rivalries between and among the great monotheistic religions were contested. Because the European powers expanded across the oceans and continents of the world, the events of this area and this period had an influence that extended globally, down to the present day.

A religious war is one of the ultimate expressions of religious intolerance. A holy war, in which the enemy’s population is targeted for destruction because of its religious beliefs, is the final terrible extension of persecution. Not all combatants in religious conflict have shown the commitment to destroying and killing enemies recently demonstrated by jihadists; wars of religion have often been defensive, to stop persecution or protect coreligionists from it, as well as aggressive, to allow the imposition of religion on others. But once a religious dispute spills over into war, it tends to harden attitudes on both sides. Nothing is more immediately destructive for concepts of religious freedom and mutual respect than war waged in the name of faith.

The Enduring Appeal of Crusade

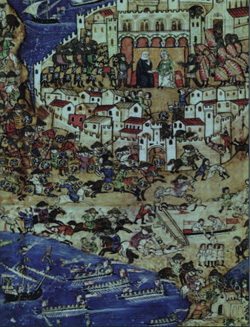

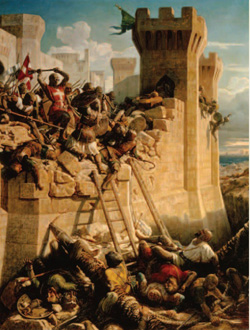

The Crusades to the Holy Land and the associated Western European occupation of parts of the Levant (1096-1291) were originally undertaken for the defense of Eastern (Greek Orthodox) Christians from Turkish oppression and to free the holy places of the Christian faith from Muslim occupation, but they became wars of European expansion. When the last European stronghold on the mainland of Asia fell in 1291, in many ways it marked the end of an era. However, while there were to be no more general crusades to the Holy Land—no more expeditions, that is, which drew volunteers from across Christendom, and which conducted campaigns in Palestine and the surrounding region—this was not the end of crusading.

The Fall of Tripoli to the Muslim Mamluks. The battle occurred in 1289 and was an important event in the Crusades, as it marked the capture of one of the few remaining major possessions of the Crusaders.

First, although we now know the Holy Land was lost for good, this was by no means obvious to Western Christians in the fourteenth century or for two centuries thereafter. The idea that a great crusade against the Turks would mobilize all of Christendom appealed to statesmen and soldiers in Europe well into the seventeenth century.

Second, it is often forgotten that, although Western Christians had no strongholds on the mainland of Asia in the fourteenth century, Armenian Christian principalities there survived; moreover, Western “crusaders” maintained control over a number of islands and coastal enclaves in the eastern Mediterranean basin: Cyprus was a Christian kingdom, for example, well into the sixteenth century. Both defensive and offensive military campaigns continued to be conducted along the Mediterranean littoral, sometimes in alliance with indigenous Christian princes.

Third, the notion of crusade had been extended in the mid-twelfth century to encompass the reconquista of the Iberian Peninsula and the wars of conquest of the Teutonic Order in the Baltic region. These wars continued into the fifteenth century.

Fourth, from the mid-fourteenth century, the Turkish threat was no longer located only in the Near East. The Seljuk Turks, who had taken the distant holy places of Christianity in the eleventh century, were supplanted by the Ottoman Turks, who drove from Central Asia into the Near East and then into Europe, albeit only (at this stage) Europe’s eastern borderlands.

Furthermore, in this period, as long as wars were against pagans, infidels, or heretics, then contemporaries typically regarded them as “crusades,” whether or not they met the original criteria for a formal crusade and regardless of whether they were undertaken in the Baltic, Iberia, northwest Africa, Egypt, the eastern Mediterranean, or southeastern Europe—and this meant that they were not just conducted by Spaniards, Portuguese, Teutonic Knights, Hungarians, Serbs, or Cypriots. Campaigns against pagans and Muslims on the southern and eastern marches of Latin Christendom attracted interest, sympathy, donations, and volunteers from across Europe. The potent lure of the crusade, even as far northwest as the British Isles, is immortalized by Geoffrey Chaucer in the “Knight’s Tale,” in his Canterbury Tales, with its roll call of locations in which the anonymous protagonist had fought: at Alexandria in Egypt, around the eastern Mediterranean, and in Turkey; in Prussia, Russia, and Lithuania; and in Spain and Morocco. These were, as Chaucer makes clear, the campaigns of a “Christian man,” fighting “for our faith” against the “heathen.” 2

Iberia, North Africa, and Eastern Europe

The height of wider Christian participation in the reconquista had been in the thirteenth century, but parts of the Iberian Peninsula remained under Moorish rule until 1492, when the Emirate of Granada finally fell to the armies of Ferdinand II and Isabella I, joint sovereigns of Aragon and Castile and León—founders of the modern state of Spain. Meanwhile in the 1410s, the Portuguese and Spanish had begun to extend their military operations to North Africa, from whence the Moors drew support. TFerdinand II of Aragonhus, wars between Christian and Muslim continued off and on throughout the period; they also continued to attract foreign Christian volunteers. Contingents from France and Scotland served against the Moors in the late fourteenth century. Englishmen crusaded against the Moors in Spanish armies in the 1370s and in Portuguese armies in North Africa in the 1470s. In 1511 Ferdinand II of Aragon launched a crusade across the Strait of Gibraltar into Africa that attracted English and French contingents.

The Battle of Grunwald, in which a Polish-Lithuanian army, led by Polish King Wladyslav II Jagiello, defeated the knights of the Teutonic Order, 1410.

Meanwhile, in the second half of the fourteenth century there had been an almost permanent crusade in the lands bordering the eastern Baltic, conducted by the Order of Teutonic Knights against the pagan inhabitants of Prussia, Lithuania, and Livonia (the medieval kingdom of Lithuania extended far beyond the borders of the modern nation). But the Teutonic Order could draw on support from more than only German knights. As the most recent historian of the order observes, among those who crusaded in Prussia and Lithuania were many “Frenchmen, Englishmen, Scots, Czechs, Hungarians, Poles, and a few Italians.”3 They included Henry Bolingbroke, later King Henry IV of England.

However, as the Teutonic Knights acquired more and more territory they increasingly became more and more like a secular state. They also increasingly became entwined with neighboring kingdoms, some of them Christian, and so found themselves “crusading” against the Catholic Poles and the Orthodox Russians. Then around the year 1400 the Lithuanians converted en masse to Christianity, and the crowns of Lithuania and Poland were united in marriage. The combined power of the Polish-Lithuanian union proved too much for the Teutonic Knights, who in 1410 were badly defeated at the First Battle of Tannenberg. The order ceased to be a major player in the area thereafter. The era of Baltic “crusades” was at an end.

One reason for the conversion of the Lithuanian elite, which then was imposed on the mass of the people, was precisely in order to gain Polish help against the Teutonic Knights. Although the sincerity of the original conversions is doubtful, once the Lithuanians were officially Christian, preaching and conversion eventually followed in subsequent generations. In a sense, then, the order could be said to have achieved part of its goals, in that it helped to obtain the conversion of many pagans to Christianity! However, it remains an open question whether conversion would not have been more readily effected by missionary activity than by wars of conquest that chiefly served to enrich and increase the power of the Teutonic Order.

Suppressing the Hussites

Germans were still able to crusade close to home in the fifteenth century, however, against the Hussites in Bohemia and Silesia in the 1420s. In the four years after the martyrdom of John Huss in 1415, his followers in what today is the Czech Republic and eastern Poland organized themselves, and in 1419 they rose in revolt. Pope Martin V called on all Christians to take up arms against the followers of Huss, though in fact the armies that subsequently fought the Hussites were drawn solely from the Holy Roman Empire and Poland. The emperor Sigismund led four “crusades” into Bohemia and Silesia, but regularly suffered defeat at the hands of the Hussites, whose armies combined technological innovation (including the first widespread use of firearms) with extraordinary religious fervor. Eventually, however, the German Catholic forces used their superior numbers to obtain some military successes, the Hussites divided into factions, and in 1436 a compromise peace was negotiated. It extended some liberties and limited diversity of religious practice to the Bohemians (which a century later became the basis for the widespread adoption of Protestantism), but restored the authority of the emperor and the Papacy.

These wars were, on the part of the Hussites, defensive: initially they did not attempt to impose their religious views on Catholics in Bohemia and Silesia, or to export the gospel of Huss outside their homeland; but they were determined to worship as they believed God commanded, and to prevent persecution. Yet there was an alternative to taking up arms, which was to undergo martyrdom. As the historian Philippe Contamine points out, this was advocated by one Hussite group, the Union of Bohemian Brothers. Their leading theologian, Peter Chelcicky, “preached nonviolence. Chelcicky railed against those who scrupled to eat pork on Friday but lightly shed Christian blood. According to him the first pacific age of the church was also its golden age; Christian law as a law of love prohibited murder, with the result that adepts of this law were certainly obliged to obey the state and to render to Caesar that which was Caesar’s, but to refuse . . . military service.”4 But as Contamine observes, this tendency “was at odds” with another—widely influential among the followers of Huss—that favored war. Swiftly the rhetoric of the Hussites passed from “justifying resistance to the pretended crusaders in the name of truth” to defending “the fatherland” against foreign invaders.5 The wars thus took on an ethnic and secular, as well as religious, character.

The Siege of Acre took place in 1291 and resulted in the loss of the Crusader-controlled city of Acre to the Muslims. It is considered one of the most important battles of the time period. Although the crusading movement continued for several more centuries, the capture of the city marked the end of further crusades to the Levant.

Furthermore, once the Hussites had enjoyed sustained success against Sigismund’s armies, they had the opportunity to impose their views on others by force, and this was one of the chief reasons for the splintering of the movement into factions. The Taborite and Orebite brotherhoods, whose members were the most rigorous and zealous of the Hussites, wanted “to force the practice of Communion in both kinds upon the citizens” of cities that “had remained Catholic” and loyal to the emperor.6 While some Hussites argued for “a tolerant approach as a necessary concession to achieve unity” in Bohemia-Silesia, others saw tolerance “as a serious betrayal of their fundamental religious principles.”7 Eventually the Taborites waged war against those they saw as unduly moderate—it was the civil war among the Hussites that allowed Sigismund finally to achieve a victory despite his series of defeats in the 1420s and early 1430s.8

Thus, as so often, once war was joined it created its own dynamic. The Hussites’ campaigns ceased to be solely defensive, and under the pressure of war many of them became intolerant and used force to impose their religious views on others. In the meantime, the religious character of the wars had made them very bitterly fought—the “crusaders” were rarely willing to show mercy to heretics, who responded to atrocity with atrocity. As recent research indicates, the 15 years of the Hussite wars were truly catastrophic in terms of the destruction wreaked on local communities, especially in Silesia.9

The Ottoman Threat

Meanwhile, from the mid-fourteenth century, the Ottoman Turks had pushed into Europe. After their victory over the Serbians at the epic Battle of Kosovo in 1389, the Ottomans expanded through southeastern Europe, gradually conquering the region’s Greek Orthodox princes but being steadfastly defied by the important (and Roman Catholic) Hungarian kingdom. However, Western Europe was not seriously threatened by the Turks before the 1520s, and while calls for help in campaigns against the Ottomans stimulated a significant response in the West in the late fourteenth century, they drew only a limited response in the 125 years after the disastrous denouement of the so-called Crusade of Nicopolis in September 1396.

The crusade was reminiscent of the original Crusades, in its pan-European appeal, which transcended even the Great Schism (discussed below), and in the transnational composition of the Christian forces. The bulk of the crusaders’ army was composed of the forces of the Hungarian king, including troops from across Central and Eastern Europe: Bohemia, Bosnia, Carinthia, Styria, Transylvania, and Wallachia. But it also included many contingents from Western Europe: Burgundy (then virtually an independent kingdom), England, France, Germany, Spain, Venice, and the Knights Hospitallers of the Order of Saint John. And while no kings took part, the elite of Latin Christendom was represented: the Germans were led by Frederick of Hohenzollern; the French, Burgundians, and possibly the English were led by the duke of Burgundy’s son and heir, John, count of Nevers; by Philip of Artois, high constable of France; and by two famous French soldiers, the Maréchal Boucicaut and Enguerrand de Coucy, count of Soissons, each of whom was celebrated across Christendom as the very model of a medieval general and knight-errant.

The defeat of the Christian army on September 25, 1396, at Nicopolis, on the Danube, was a decisive blow to the Christian cause in the Balkans. The Crusade of Nicopolis was in some respects the end of an era; it was the last great transnational crusade.

Although Burgundians were again to see service outside the walls of Nicopolis, aiding the Wallachians in 1445, the Polish and Hungarian armies in the so-called Crusade of Varna in 1444 were joined by only a few Czech, German, and Italian troops, despite the appeals of Pope Eugenius IV; the crusade ended in a defeat at Varna (on the Black Sea coast in modern-day Bulgaria) more disastrous than that at Nicopolis. Likewise, only a small force of Italian troops and ships went to aid the Greek Orthodox defenders of Constantinople during its final siege by Sultan Mehmed II in 1453. Three years later there was a very limited response to Pope Callistus III’s efforts to raise troops to relieve Mehmed II’s siege of Belgrade, despite a papal pronouncement that the city’s fall would endanger the whole Christian world. Thanks to the leadership of János Hunyadi and the religious zeal of the defenders, the siege ended in a remarkable Christian victory, celebrated by the ringing of church bells all over Christendom. But it owed little to Western aid. Several subsequent fifteenth-century popes, including Pius II, a veteran of Varna, attempted to organize a united Christian coalition against the Turks, but although in 1480 the Ottomans briefly occupied Otranto, on the Italian peninsula itself, papal efforts received a lukewarm response until the sixteenth century.

The lack of enthusiasm in Western Europe in the fifteenth century has been attributed to the shock of the defeat at Nicopolis. Yet it is also the case that, for most of the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the Catholic kingdoms of Central Europe—Bohemia, Hungary, and Poland—succeeded reasonably well in their wars with the Turks, despite some defeats. In an era when the Great Schism of the Papacy (1378-1417) divided Christendom, between initially two and later three rival popes, for nearly 40 years, and when the emergence of prominent “heretical” movements in England (the Lollards) and Central Europe (the Hussites) posed the first major challenge to the Papacy’s authority for 200 years, Western Europeans made aiding their fellow believers against Muslims a low priority, especially as long as the Ottomans were being largely kept at bay and seemed a very distant threat.

These attitudes, however, meant that the fate of Southeastern Europe’s Orthodox Christians was sealed. They henceforth faced sustained repression and at times brutal persecution by the Ottomans, which resulted in many conversions to Islam. Although Orthodox Christian communities survived, abhorrence toward Muslims was engendered and attitudes were entrenched that literally took centuries to erase—attitudes of suspicion and hatred toward both Muslims (the conquerors and oppressors) and Roman Catholics (perceived as having abandoned their fellow Christians). The separate identities of Bosnians, Croatians, and Serbians in the Balkans are largely defined not by language, but by religion—historically and culturally, Bosnians were Islamic, Croatians Catholic, and Serbians Orthodox. The wars between these three religio-ethnic groups of the 1990s, and the genocide practicd by Serbian extremists against Bosnians (many of whom were not actually Muslim), were in a sense the last rites of the religious wars begun in the 1370s.

Summing Up the Period 1370s–1520s

In sum, throughout this period, religion helped to generate conflicts, albeit only on the fringes of Europe. Yet although these wars were waged in Christendom’s borderlands, men from Central and Western Europe were consistently drawn to them, motivated by religious fervor and particularly by the concept of “crusade.” Patterns were set that were to be important in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when Christendom and Islam directly confronted each other, even while Catholic and Protestant tore Christendom apart. In particular, the enduring emotional appeal of the crusade was to be extremely influential. In 1494 King Charles VIII of France had made serious plans to crusade against the Turks. He told one of his confidants that he would “not shed any more blood, nor expend his treasure [on wars with Christians] until he had overturned the empire of the Ottomans or taken the road to Paradise.”10 So powerful was the concept of crusade in Western culture that Protestants, as well as Catholics, were to be influenced by it in waging the confessional wars of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries; crusading was to be the model for Christians fighting the Ottomans and for Catholics and Protestants fighting each other. It was a model of great heroism and commitment on campaign and in combat, but frequently of great brutality and cruelty as well, one which tended to entrench rather than erode enmity between adherents of different faiths and confessions. As we shall see in the next article, the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century wars of religion were to be among the largest, most long-lasting, and most sanguinary conflicts in history, unmatched before the wars of the twentieth century.

- These articles are based on D. J. B. Trim, “Conflict, Religion, and Ideology,” in Trim and F. Tallett, eds., European Warfare, 1350–1750 (New York & Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), chap. 13.

- Canterbury Tales, Fragment I, ed. Ralph Hanna, Larry D. Benson, and Robert A. Pratt, in The Riverside Chaucer (New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press, pb. ed., 1988).

- William Urban, The Teutonic Knights: A Military History (London: Greenhill, 2003), p. 174.

- Philippe Contamine, War in the Middle Ages, Michael Jones, trans. (Cambridge, Mass. & Oxford: Blackwell, pb. ed., 1986), p. 295.

- Ibid.

- Stephen R. Turnbull, The Hussite Wars 1419-36 (Oxford: Osprey, 2004), p. 15.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Contamine, p. 304.

- Quoted in Yvonne Labande-Mailfert, Charles VIII et son milieu (Paris: C. Klincksieck, 1975), p. 180.